Article: Artists, Collectors, and Dutch Drawings in the Seventeenth Century

Most, if not all, seventeenth-century Dutch artists began drawing in earnest as the underlying basis of their training.1

Apprentice artists drew relentlessly in order to master everything from the rudiments of form to the most advanced aspects of lighting, composition, and expression. Students worked in stages, first by copying two-dimensional works, especially prints, and inanimate three-dimensional objects, such as plaster casts of ancient sculpture or articulated wooden dummies. After time, they drew from live models in the studio or ventured outside to record the world around them. As students, their competence and progress were necessarily measured through their drawings. As professionals, most artists continued to practice and hone their skills on a regular basis. Popular at the time was the legendary adage of the Greek painter Apelles, Nulla dies sine linea—literally, “No day without a line.“2

For some artists, an even deeper fundament can be found in certain tales by early biographers, though these are less discussed in the art historical literature due to their easy labeling as myth: specifically, drawing as a passion of the artists as children. Not all of the great masters of the era came from artistic families where ready materials were at hand, and the instruction free of charge and encouraging. Those from other families, one reads, were often resourceful and even amusingly insubordinate in their innate zeal for drawing. Many such stories were told with relish by Arnold Houbraken (1660 – 1719) in his voluminous Groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders (Great theater of Dutch painters) published in 1718 – 21, an indispensable source of biographies of seventeenth-century Dutch artists.3

Houbraken tells us that Frans van Mieris (1635 – 1681) (see cat. nos. 53 & 54), whose drawings are relatively scarce today, was in the habit of drawing figures and animals in charcoal on the walls of his father’s workshop as a boy, leading to his placement with a local drawing master.4

That the act of drawing made possible the early recognition of talent in a child is a trope that stretches back to stories of early Renaissance artists.5

Houbraken’s account of the youth of Govert Flinck (1615 – 1660) (see cat. no. 19) offers an extreme example of such an origin story.6

His father, who was a silk merchant and tax official in Cleves, was appalled by his son’s desire to become an artist. The young Flinck was therefore absolutely forbidden to make drawings. Houbraken quotes his father’s outrage: “God preserve me that my own son should become a painter. Those sorts of people are mostly libertines, and they lead uninhibited lives!” Despite this painful rejection, Flinck, the story goes, used his spare change to buy drawing materials and a lamp, so that he could copy prints lent to him by a local glass painter after everyone was in bed. His father discovered him one night, and in a fit of anger tore up all his drawings and beat him severely. It was only after meeting the Mennonite (and one presumes perfectly well-mannered) painter Lambert Jacobsz that his father finally allowed Flinck to leave the house to train with Jacobsz in Leeuwarden. He would later complete his training with Rembrandt in Amsterdam, where he eventually settled and became a highly successful painter. Flinck’s story is one like many others, both told and untold, that show how drawing was not only a bedrock of artistic practice in both instructional and professional terms, but could also have undertones of early passion, struggle, and delight.

Painting and printmaking each required a greater range of equipment and training. The purpose of those two mediums was almost always the creation of artistic end products from the outset. An artist’s body of drawings, however, especially at the opening of the seventeenth century, was still a type of material largely held privately by the artists themselves. Drawings were often functional in nature and kept in the studio for potential use. Sketches, figure studies, compositional studies, and other types of preparatory drawings served in the production of paintings or prints — and, on occasion, for the production of more finished drawings intended for gift, sale, or exchange.

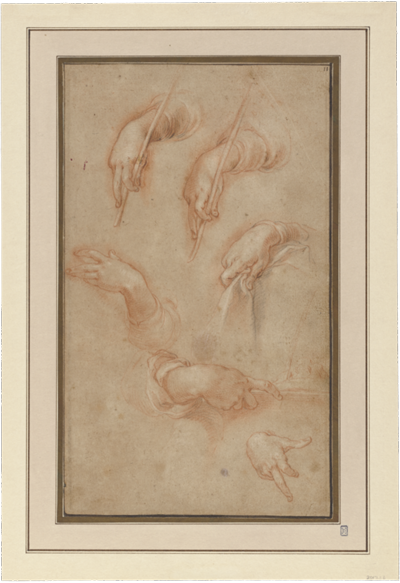

An artist’s collection of drawings was a valuable asset, built slowly over the years, and not to be parted with lightly. Some collections were passed down through artist families, such as that of Abraham Bloemaert (1566 – 1651), many of whose studies composed an atelier thesaurus (or visual “treasury”) that remained in the workshop (cat nos. 1 & 2).7

The publication of his Tekenboek (Drawing Book) around 1650 made an engraved and printed selection of these studies available to the larger public, and it was obviously received well, having been reprinted several times into the eighteenth century.8

An artist’s studio remains could also pass between a master and pupil, or be actively acquired by a former pupil. Many drawings by Adriaen van Ostade (1610 – 1685) (see cat. no. 62) found their way into the hands of Cornelis Dusart (1660 – 1704).9

One of Van Ostade’s drawings greatly inspired Dusart’s Milk Seller Before a House or Inn in the Peck Collection (cat. no. 63), though in this instance we know he had access to Van Ostade’s own drawing of the subject before his master died, likely while Dusart was still a late-stage apprentice.

The dispersal of the studio collection of drawings owned by Rembrandt (1606 – 1669) offers a special case. In 1657 – 58, he was forced to sell nearly all his possessions to prevent bankruptcy, including his entire collection of art, antiques, and curiosa. Among the items dispersed were twenty-five albums of drawings, which must have contained a significant number of sheets, likely over 1,000.10

His collection contained many drawings of his own making, as well as a large number by other masters that he had acquired with great effort and expense, including scores of drawings by Italian Renaissance artists. Rembrandt had the unusual distinction of witnessing during his lifetime his own stock of drawings fall unintendedly into the hands of others, who no doubt greatly appreciated them. There is also evidence he had kept a large selection of drawings by his pupils in these albums.11

Before his insolvency, Rembrandt ran what was easily the largest atelier in Amsterdam. He trained dozens of artists and employed numerous assistants, some of whom were quite talented and whose drawings remain difficult to distinguish from both his own and those by other members of his studio.12

As sobering as it is to consider, all of Rembrandt’s drawings in the Peck Collection were likely part of the sales that deprived the artist of so much of his valued work (though one could argue that the sales also ensured the preservation of working material that could have otherwise easily been lost). His Seated Man Warming His Hands by a Fire (cat. no. 38) and Man with a Walking Stick Wearing a Fur Cap (cat. no. 24) are just the types of studies that he would have kept on hand for potential use. In fact, he likely used the latter as a model for one of the figures in his famous etching, Christ Healing the Sick (The Hundred Guilder Print). Reinforcing the notion that such drawings were not meant to circulate beyond the studio is Rembrandt’s own handwritten note on Studies of Women and Children (cat. 17), which is the last of his self-annotated drawings to reach a public collection.

The two other drawings by Rembrandt in the exhibition offer examples of two equally important but very different sides of his drawing practice. The magnificent Noli me tangere (cat. no. 39), depicting the moment that the newly risen Christ tells Mary Magdalene not to touch him, shows him working “from the imagination,” or uit den geest, in which biblical scenes or other types of narrative works drawn from history or mythology would be freely composed with the mind’s eye. Hundreds of such drawings survive by Rembrandt and his pupils, many depicting exactly the same scenes, leading scholars to suspect that Rembrandt would often assign a particular narrative for his students as part of their routine training.13

This required them to engage closely with the text of a story, perhaps together with the previous visual tradition in the form of prints and other drawings, and to recapitulate in their own visual terms the moment’s inherent drama, meaning, and emotional impact. Rembrandt and his students ultimately used some of these studies to compose paintings, though these were exercises and not preparatory studies from the outset. Rembrandt’s former pupil, Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627 – 1678) (see cat. nos. 22 & 23), who wrote a substantial treatise on the art of painting, repeatedly mentioned that drawing was an activity for the evenings, especially in winter when the days were short (and the natural daylight needed for painting in color fleeted early).14

Drawing exercises would have kept the workshop busy and the students diligent. Flinck’s own Sacrifice of Manoah (cat. no. 19) shows him working purely from the imagination shortly after he left Rembrandt’s workshop, swiftly thinking through the staging and motions of a dramatic biblical scene without recourse to models or other material. Of particular interest to Rembrandt and his pupils were moments of divine manifestation, such as the unexpected revealing of Christ’s identity in his Noli me tangere, or the shocking appearance of the angel in Flinck’s Sacrifice of Manoah.

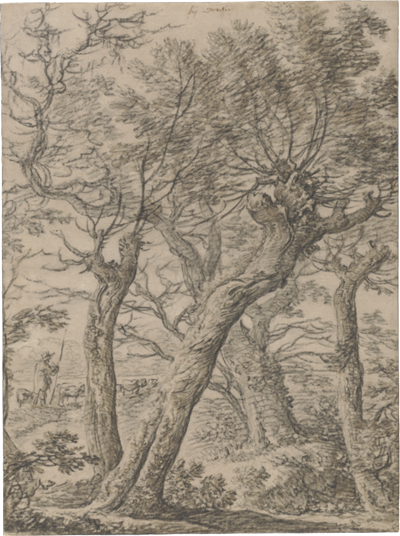

Rembrandt’s Landscape with Canal and Boats (cat. no. 41) offers an example of another important side of his drawing practice, working naar het leven, or “from life.” Rembrandt would wander the country roads and dikes outside of Amsterdam, perhaps with company or sometimes alone, where he recorded the natural surroundings with his own distinctive vision. He mostly produced landscapes in a fifteen-year period between 1641 and the mid-1650s.15

He did so primarily in his works on paper, using a broad graphic vocabulary to evoke light, air, and depth. While his two dozen or so landscape etchings reached a broader audience than his drawings, the latter by far comprised the greater portion of his landscape output, numbering well over 100 sheets today. His inventory reveals he held onto most of his landscape drawings, with his inventory listing three of his twenty-five portfolios of drawings devoted to them.16

Many of Rembrandt’s most remarkable landscape drawings actually ended up in the hands of Flinck’s son, Nicolaes Anthoni Flinck (1646 – 1723), who became a great collector of drawings.17

Nicolaes was one of the first to stamp his drawings with a collector’s mark (the letter F), though the absence of such a mark on the Peck Collection landscape suggests it was not part of his collection. It is entirely possible that he inherited Rembrandt’s landscape drawings from his father, who may have acquired a selection of them at the bankruptcy sales. The elder Flinck would not have been the only artist to avail himself of Rembrandt’s collection. We know from the inventory of the painter Jan van de Cappelle (1626 – 1684) that he owned upward of 500 drawings by Rembrandt, likely including the portfolio that contained the Peck Collection’s Studies of Women and Children (cat. no. 17).18

Rembrandt, Flinck, and Van de Cappelle were not the only artists who were serious collectors of drawings by others at the time. Pieter Saenredam (1597 – 1665), Philips Koninck (1619– 1688), and Caspar Netscher (1635/36 – 1684) all came to possess significant numbers of drawings by other masters.19

It comes as no surprise that artists themselves, especially if they had enough financial means, would assemble collections of drawings in earnest. What became increasingly blurred, however, was the distinction between the artist as collector of studio material and the artist as a collector-connoisseur.20

In terms of using other artists’ drawings as studio material, a certain amount of artistic appropriation indeed took place. Saenredam, for example, made use of the Roman sketchbooks of Maarten van Heemskerck (1498 – 1574), then in his possession, to paint an image with the church of Santa Maria della Febbre nearly a century after Heemskerck made his drawing of it.21

Such a use would not likely have raised any eyebrows. There were limits, however, and one story points to the fact that contemporaries would have frowned upon widespread appropriation. Houbraken reported that the artist Philips Wouwerman (1619 – 1668) on his deathbed had his collection of figure studies by the then long missing and presumed dead Pieter van Laer (1599 – after 1642) (see cat. no. 13) burned before his eyes in order to hide the fact that he had been using them for some time to add figures to his paintings.22

This dramatic legend passed down in Haarlem art circles before reaching Houbraken’s ears. Interestingly, and lending credence to the tale, at least one figure study by Van Laer survives (perhaps escaping the fire) that clearly served for a painting by Wouwerman.23

Such a case, if true, was uncommon. Most of the avid artist-collectors in this era did not acquire drawings for reuse in the studio as preparatory material. Purely as connoisseurs, artists were the best equipped to understand and acutely appreciate the materials, techniques, styles, and functions of drawing as an independent medium.

The class of passionate collectors who were not themselves professional artists had certainly found drawings attractive before the seventeenth century and gladly acquired them, especially if they were more finished works rather than preparatory material that had somehow escaped the studio. The signed and dated Man with Plumed Hat, Depicted as Sculpted Bust from 1605 by Jacob Matham (1571 – 1631) (cat. no. 5) is a good example of the type of freestanding drawing that would appeal to collectors. His former pupil, Jan van de Velde II (1593– 1641) (cat. no. 16), likewise a printmaker by profession, also made finished drawings for collectors on the side. With great precision, both artists used drawing as a means to promote their skill with a pen by freely adapting the more lapidary graphic line of the engraver. Archival documents from 1641 show that Van de Velde actually received one of the earliest-known commissions to create a series of drawings specifically of his own invention (to be landscapes and “perspectives” according to the patron), though unfortunately none appear to have survived.24

What changed dramatically in the seventeenth century was the rise of a widespread accumulation of drawings in general by these collectors. Such fervor appears to have shifted the work priorities of certain artists, who almost certainly increased their production of drawings in order to take advantage of this increase in demand. Jan van Goyen (1596 – 1656) (cat. nos. 36 & 37), for example, and the brothers Herman (1609 – 1685) (cat. nos. 12 & 28) and Cornelis Saftleven (1607 – 1681) (cat. nos. 27 & 51), to name but a few, devoted a considerable portion of their artistic activities to the production of finished drawings. Many of these give every appearance of having been drawn directly from nature, but some artists actually crafted their drawings to look this way by making use of their stock of sketches and studies. Boy with Two Laden Donkeys in the Hills by Willem Romeyn (c. 1624 – 1695) (cat. no. 66) is deceptively naturalistic, but the figure of the boy comes from a study that must have been made over three decades earlier, and two of the pack animals were also the subject of separate study drawings. Without such evidence, it can often be difficult to tell if an artist made a landscape drawing mostly or partially on-site, or whether it was entirely the product of work in the studio. Crafting the convincing appearance of having been taken from life was more important than adhering to the actual principle of doing so.

Further telling of an increase in the appreciation of drawings in this era is the more frequent production of autograph copies. Over time, art historians have gained a better view of the extant drawn oeuvres of many artists, and this has made clear that some artists certainly copied their own drawings from time to time. Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598 – 1657) brought a cache of drawings with him back from Italy around 1629, after which he occasionally made new versions of his Italian subjects.25

Cliffs, Possibly near Bracciano in the Peck Collection (cat. no. 8) bears an Italian watermark and was likely the prototype for two later versions in which he freely varied the style, but not the composition itself. Pieter de Molijn (1595 – 1661) (see cat. no. 45) made a number of relatively exact copies of his own drawings in the early 1650s, likely to meet demand.26

Travelers in an Italian Landscape by Nicolaes Berchem (1621/22 – 1683) (cat. no. 44), one of his best and most extensively finished drawings, is actually a copy made through innovative technical means. This sheet, dated 1655, reproduces in reverse his drawing of the same composition from 1654 that he used to make his celebrated painting of the subject now in the British Royal Collection. It appears that Berchem made a counterproof of his 1654 drawing to create a basic outline, and then worked it up with a number of washes carefully applied by hand.27

That Molijn’s and Berchem’s copies date to the early 1650s is perhaps no accident. Van Goyen’s peak production of finished drawings comes from this period as well. One might reasonably ask if there were any factors that drove what appears to be a sudden spike in the demand for drawings. The answer possibly relates to the availability of paper at the time. After widespread European warfare ended with the Treaty of Münster in 1648 (ending the Eighty Years’ War) and the Peace of Westphalia the same year (ending the Thirty Years’ War), trade routes once again opened in full. Papermakers likely found a ready market in the Netherlands, which did not make much paper suitable for drawing at that point. A whole new range of watermarks also emerged in this period, such as the Seven Provinces and Arms of Amsterdam, which made clear their role in serving specifically for the export market in the Netherlands after being manufactured in Germany, Switzerland, or France.28

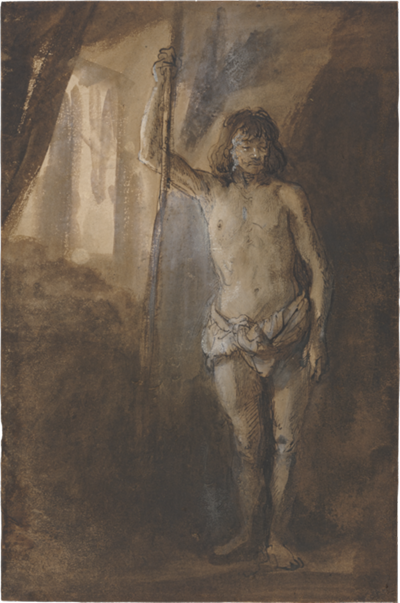

What we call finished drawings, those that seem more or less autonomous, and often signed, were not the only type of drawings that captured the attention of collectors. Houbraken reliably tells us, for example, that connoisseurs would clamor over the figure studies on blue paper by Jacob Backer (1608– 1651), such as his Study of a Man Holding a Glass (cat. no. 21).29

Most of Backer’s figure studies probably first appeared on the market as part of the estate of his brother, Tjerk, who died in 1659.30

Even though Backer had retained his figure studies, it is apparent that he rarely made use of them for his paintings. The same can be said for those by Dusart, such as his Study of a Young Man Standing with His Foot on a Stool (cat. no. 64), which was probably once part of the album of 251 figure studies listed in his postmortem inventory, only a fraction of which survive today.31

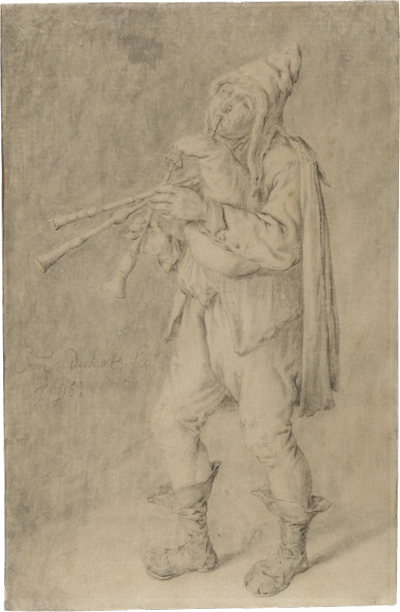

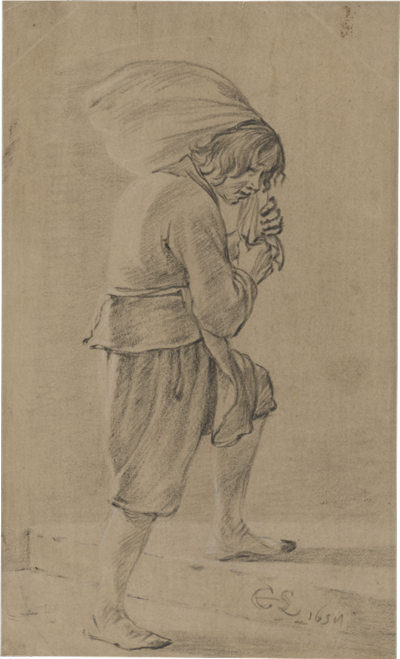

Even though he held onto his figure studies, Dusart also executed many finished drawings for collectors, such as his signed and dated Bagpiper (cat. no. 65). This is one of the few seventeenth-century Dutch drawings on the then-costly and unusual support of Japanese paper, which had great appeal for collectors at the time. Cornelis Saftleven also drew a remarkably large number of figure studies throughout his career, few of which he used for his paintings, but in his case one cannot help wondering if he crafted some of those that he monogrammed and dated, such as Study of a Boy Carrying a Sack (cat. no. 51), specifically to cater to a demand among collectors for this type of work.

In general, the use of the term “finished drawing” seems both imprecise and too broad in application. Figure studies could function as autonomous works of art whether they were steered toward collectors or retained by the artists themselves. Many of the drawings that survive from the era could be said to fall into a category that tends to escape distinction: the seemingly finished drawings that artists made with no immediate or obvious intention to part with them. Artists often assiduously produced drawings for their own keeping without any need for them to function as ready inventory, reference drawings, or pedagogical material. Rembrandt’s landscape drawings could be said to fall into this category, as well as many of the beautifully executed figure studies from which many artists seem to have derived a great deal of pleasure in making and preserving.

When speaking of the functions of drawings, it is useful to return once again to Houbraken’s life of Govert Flinck. On Sundays, we are told, after finishing his religious obligations, Flinck would put down his brushes and traverse the canals of Amsterdam to visit artists and collectors.32

He was not in the habit of frequenting the taverns where artists gathered to drink in the evenings (one gets a sense of his father’s lingering voice in this regard), but he did like to socialize with his colleagues on occasion to discuss the usual matters of their profession. The collectors he most often visited, Houbraken informs us, were none other than Jan Six (1618 – 1700) and Johannes Uytenbogaert (1608 – 1680). Flinck was no longer a boy sneaking visits to a local glass painter in Cleves to see his modest collection of prints, but now a major name in the Amsterdam art world with an open invitation to view two of the most substantial and esteemed collections of paintings, drawings, and prints in the Netherlands.

According to Houbraken, Flinck not only used these visits to learn how to distinguish the styles of various masters, but also to glean the “beautiful” from them in ways that he sought to apply to his own works. The remarkable openness of these collectors to Sunday visits from respected artists such as Flinck goes unmentioned, but one would like to imagine that the discussions that took place while viewing their portfolios containing countless drawings and prints of the highest quality offered a congenial end to their week. Six and Uytenbogaert were decidedly not men of leisure; they were highly active citizens engaged in the most pressing political and business matters of the day. For them, such collections functioned in far more meaningful ways than merely conferring status. These Sunday meetings provided all at once a socially and art-theoretically significant interchange between artists and art-lovers, a wellspring that lent the learned and curious great satisfaction, and as a source, most simply, of the mind-stilling visual wonder that the best artists could achieve. When we look at drawings and discuss them in terms of their function — their original function — we are still only telling part of the story. These drawings function today in the same ways they already did for Flinck, Six, Uytenbogaert, and every artist and art-lover in between who found and continue to find in them respite, recharge, and inspiration.

References

For drawing as a basis of training for seventeenth-century Dutch artists, see Amsterdam 1984 – 85; Bolten 1985; Walsh 1996; Van de Wetering 1997, 46 – 73; Kwakkelstein 1998; Schapelhouman 2006; H. Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 1 – 29; W. W. Robinson & P. Schatborn in Washington & Paris 2016 – 17, 5 – 16; and G. Luijten in idem, 34 – 52.

G. Luijten in Washington & Paris 2016– 17, 36.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 3, 1 – 2.

For the hero myth of the young artist in biographies, see Kris & Kurz 1979, 13 – 38.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 2, 18 – 20.

Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 361.

For the Tekenboek, see Bolten 1985, 253 – 56; Bolten 1993; Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 389 – 94; Nogrady 2009, 226 – 31; and Bolten 2017b.

Schnackenburg 1981, 60 – 61; and Anderson 2015.

Strauss & Van der Meulen 1979, 367 – 79, doc. 1656/12. Regarding his collection of drawings, see Amsterdam 1999 – 2000; and Plomp 2018, 47 – 50.

H. Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 27 – 29.

For issues related to the attribution of drawings by Rembrandt and his “School” (sometimes comprising artists who may not have studied with him but whose style is similar), see Royalton-Kisch 1992, 17 – 20; P. Schatborn & W. W. Robinson in Bevers 2022, 31 – 41; and Bevers 2022 (a review of Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, containing a major revision of Rembrandt’s drawn corpus).

For this idea, see H. Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 20. This may have consciously paralleled the practice of the Carracci academy in Bologna.

Van Hoogstraten 1678, 191; see also Corpus, vol. 5, 58, 219.

For Rembrandt’s landscape drawings, see Gnann 2021; Amsterdam & Paris 1998 – 99; and Washington 1990.

Strauss & Van der Meulen 1979, 348 – 88, doc. 1656/12, nos. 244, 256, 259.

For Nicolaes Flinck and his collection, see Plomp 2001, 106 – 07; Plomp 2018, 51 – 52; and the entry for Lugt 959 (http://www .marquesdecollections.fr). He also made a number of landscape etchings, no doubt inspired by Rembrandt’s example; see Van Camp 2010.

Bredius 1892, 37 – 40.

For these artists as collectors of drawings, see Plomp 2018.

Idem, 46.

Wheelock 1995, 349 – 53; and Plomp 2018, 46 – 47.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 2, 73.

Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, inv. no. D805; see P. Schatborn in Washington & Paris 2016– 17, 116 – 18, no. 37.

For this commission, see Fucci 2018a, 79 – 82, 273 – 274, docs. 88 – 89. The related documents were first published by Abraham Bredius in Obreen 1877 – 90, vol. 7 (1888 – 90), 112 – 13. Van de Velde died later that year, but a second document suggests that he had indeed completed one or more of the drawings.

See Roethlisberger 1969, 9, nos. 13 – 14, 99 – 100; as well as Alsteens 2015.

For a study and catalogue of Molijn’s autograph replicas, see Beck 1997. For one of these in the Ackland Art Museum (donated by Sheldon Peck in 1988), see T. Riggs in Gillham & Wood 2001, 58 – 59, no. 18.

Aside from the entry in the present catalogue, see also Fucci 2022b for Berchem and counterproofs generally.

T. Laurentius in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 28 – 33.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 1, 338.

Bredius 1915 – 22, vol. 4, 1241 – 42; and J. van der Veen in Amsterdam & Aachen 2008 – 09, 25.

Bredius 1915 – 22, vol. 1, 65.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 2, 23.