Choose a background colour

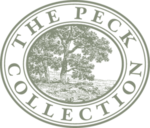

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Dutch, 1627-1678

:

Study of a Male Nude Holding a Staff, c. 1646

Pen in brown ink and wash with white highlights on paper.

11 13⁄16 × 7 7⁄8 in. (30 × 20 cm)

Verso in pencil, at center, P. Mathey / Dr. C. Hofstede de Groot / 356; at lower center, p. 04; and lower right, 296

- Chain Lines:

- Indiscernable

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Paul Mathey, 1844 – 1929, Paris (Lugt 2100b); sale, F. Muller, Amsterdam, 19 January 1904, lot 35 (as Rembrandt); Adolf Glüenstein, 1849 – c. 1917, Hamburg (Lugt 123, mark on verso); possibly dealer, C. G. Boerner, Leipzig, 1918; Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, 1863 – 1930, The Hague (Lugt 561); Sven Wingqvist, 1876 – 1953, Gothenburg; sale, Bukowski’s, Stockholm, 29 May 2007, lot 518; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, 2017, inv. no. 2017.1.43.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Hofstede de Groot 1906, 86, no. 356 (as Rembrandt); Sumowski Drawings, vol. 5 (1981), 2768 – 69, no. 1250ax (as Van Hoogstraten); Blanc 2008, 347, no. D153 (as Van Hoogstraten).

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.43

Rembrandt’s teaching methods included drawing from live models, often male pupils and assistants working in the artist’s large studio. One of his most talented students, Samuel van Hoogstraten, used saturated washes of varying tones to set this figure in space and applied hatching and white highlights to create form and dimension. The wooden beams and gabled window suggest it was made in Rembrandt’s attic, an area partitioned for student use.

Writing in his treatise on art published some thirty-five years later, Van Hoogstraten wished he had focused more on graceful movements in his early figure studies. The pose shown here, although perhaps considered “ungraceful” to the artist, continues to be utilized in drawing instruction today.

Samuel van Hoogstraten was one of Rembrandt’s most talented pupils, but is best known today for his historically important treatise, the Introduction to the Academy of Painting, or the Visible World (Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst, anders de zichtbaere werelt), published in 1678.1

It is through Van Hoogstraten’s book that we learn, or can infer, much about Rembrandt’s own teaching methods and general artistic practices.2

This included drawing from live nude models. An understanding of the proportions, forms, and movements of the human body was a central subject in Van Hoogstraten’s book.

Drawing from male nude models was certainly more common than drawing from female ones, though the latter has rightly received a greater share of scholarly attention due to the innovative and sometimes fraught nature of the practice.3

Unlike the female prostitutes often hired to disrobe as models, members of a larger studio (such as Rembrandt’s) could freely enlist their male studio assistants and fellow pupils to strip down to their loincloths. Most drawing “academies” in Amsterdam followed the Italian model of using black and white chalk on prepared paper.4

Rembrandt and his followers, by contrast, preferred to use pen and ink with wash, as here, sometimes finished with a great range of tone.5 The relatively worked-up background emphasizing a studio setting is also commonly found in his and his students’ works, as opposed to depicting a figure set in empty space.

Arnold Houbraken (1660 – 1719) tells us that Rembrandt rented a warehouse space on the Bloemgracht for drawing after live models.6

We gain a glimpse into one of Rembrandt’s group sessions through the fortunate survival of three different drawings, all in the style of Rembrandt’s workshop (though not by the master himself), showing the same model in the same pose from three different angles, along with Rembrandt’s own etching from the same session.7

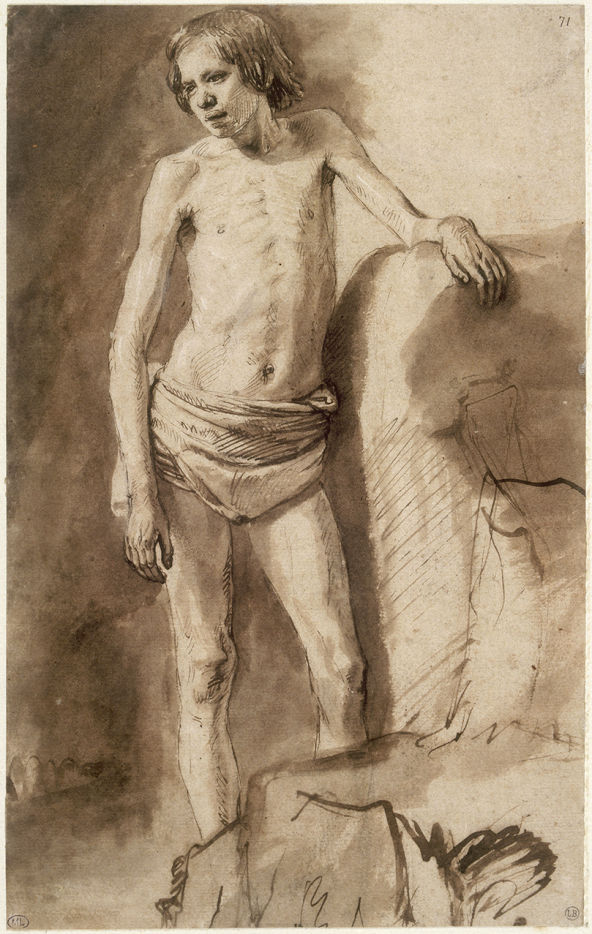

Van Hoogstraten is thought to have made one of those three drawings while seated to Rembrandt’s right Fig. 22.1.8

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Standing Male Nude, Head Facing Left, c. 1646. Pen in brown ink and brown wash with highlights in white, 247 × 154 mm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. no. rf 4713.

RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

Rembrandt made two closely related etchings in 1646, which has given rise to the premise that these three drawings were made in the same year, and, by extension, that his known students from that time, such as Van Hoogstraten and Carel Fabritius (1622 – 1654), were likely participants.9

Some sessions were held as groups, but others, like the present sheet, probably reflect an individual practice that also took place under Rembrandt’s roof; quite literally, in this case, as one sees by the architecture. This is in keeping with a 1658 document that confirms Rembrandt had partitioned spaces in his attic for his students.10

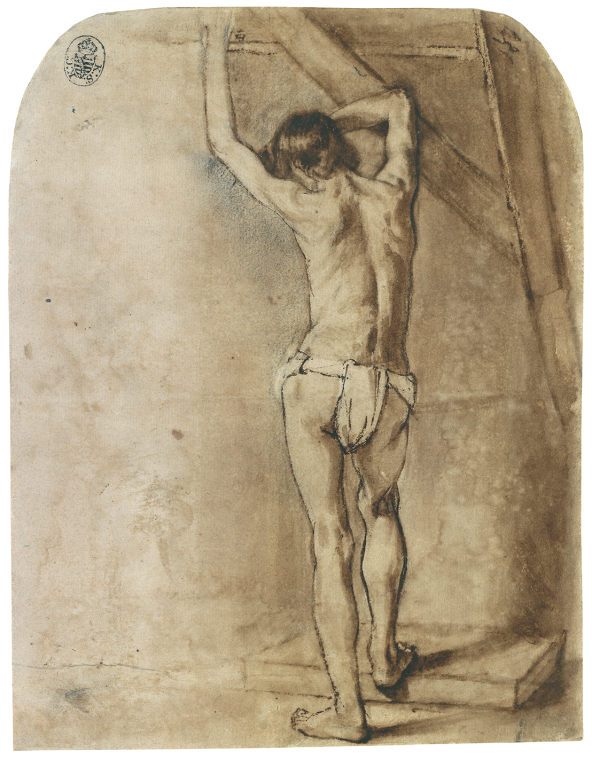

Given the diagonal beams and gabled window shown here, it seems likely that this is one of those spaces in Rembrandt’s own home, the present-day Rembrandt House Museum. A drawing attributed to Barent Fabritius (1624 – 1673) in Dresden reveals a similar space Fig. 22.2.11

Barent Fabritius, Standing Male Nude, Leaning against Beam, c. 1646. Pen in brown ink and brown wash, 204 × 158 mm. Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. c 1363.

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photograph Herbert Boswank

The attribution of the present drawing to Van Hoogstraten is by no means entirely straightforward. Originally it was regarded as a work by Rembrandt himself in the 1906 catalogue of his drawings by Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, who may have once owned the sheet.12

Its present attribution was first published by Werner Sumowski in his corpus of Van Hoogstraten’s drawings (crediting Kurt Bauch for communicating the suggestion orally).13

Sumowski gathered a number of other nude figure studies under Van Hoogstraten’s name, but it nevertheless remains difficult to reconcile all of them definitively with the rest of his drawn oeuvre, and sometimes even with each other.14

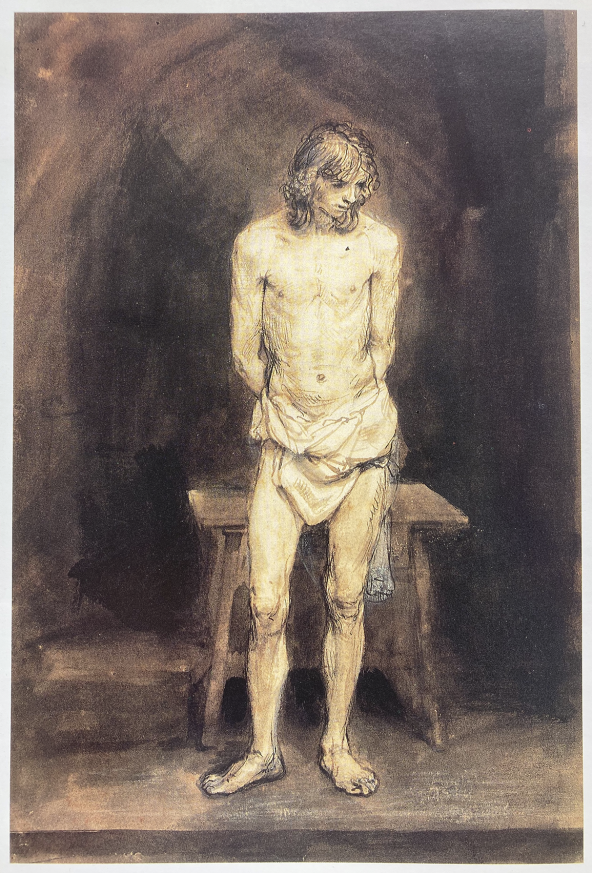

This is an understandable problem given the academy-like nature of this type of drawing, often left unsigned. This work contains particularly strong passages of pen hatching to define the limbs and torso, as one encounters to some degree in other nude studies attributed to Van Hoogstraten. He also seems to have been in the habit of lending greater attention to the loincloths, filling out their forms more carefully than his peers. While the attribution of this and other nude studies to Van Hoogstraten must remain to some degree provisional, his authorship is the most plausible. For instance, another drawing attributed to Van Hoogstraten formerly in the Koenigs collection relates in style, execution, and the use of a saturated wash background to set the figure in space Fig. 22.3.15

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Standing Male Nude, Hands Behind Back. Pen in brown ink and brown wash with highlights in white, 296 × 169 mm. Formerly Haarlem, Collection of F. Koenigs.

Van Hoogstraten tells us himself in The Visible World that he saved his figure studies from these years, but wished that the poses had been more concerned with the graceful movements of the body: “I pity myself when I look at my old academy drawings and see that we were so sparsely educated in this in our youth, as it is no more work to imitate a graceful posture than an unpleasant and disgusting one.” 16

It is ironic that the pose adopted here, with the figure merely standing and holding the staff to help maintain his raised arm, may have seemed “ungraceful” or old-fashioned to Van Hoogstraten later in life. Such a pose remains conventional in a tradition of instruction that continues unabated to the present.

If Rembrandt’s students were using each other as models, it is tempting to venture an identification of the young man volunteering his services here. Although the likeness in the drawing is only loosely given, it bears a certain resemblance to Barent Fabritius Fig. 22.4

Barent Fabritius, Self-Portrait as a Shepherd, c. 1654 – 56. Oil on canvas, 79.5 × 65 cm. Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, inv. no. gg-639.

Akademie der bildenden Kuenste Wien

Given the Rembrandtesque style of many of his paintings, it has often been assumed that Barent joined his older brother Carel in training in Rembrandt’s atelier in the 1640s, though unfortunately there is no firm evidence of his tutelage there.17

End Notes

For an introduction to and translation of Van Hoogstraten’s Visible World, see Brusati & Jacobs 2021.

See Van de Wetering 2016 for a study of the links between Van Hoogstraten’s treatise and Rembrandt’s practices as we understand them.

For the practice of drawing from live nude models in Rembrandt’s workshop, see Amsterdam 2016; and H. Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 13 – 19. For Rembrandt’s male nudes specifically, see Kettering 2011; and D. de Witt in Amsterdam 2016, 117 – 23. The chief study of Rembrandt’s female nudes is Sluijter 2006.

For an overview of the different drawing academies in Amsterdam, see J. Noorman in Amsterdam 2016, 11 – 43.

Kettering 2011, 253.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 1, 256; and Ford 2007, 59.

See H. Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 12 – 17.

Sumowski Drawings, vol. 5, no. 1253; and Paris 1988 – 89, no. 109.

New Hollstein (Rembrandt), nos. 232, 234. See De Witt in Amsterdam 2016, 117 – 23. For the attribution of one of the drawings to Carel Fabritius, see Schatborn 2006, 136 – 37.

Strauss & Van der Meulen 1979, no. 1658/3. The document relates to the sale of Rembrandt’s house, and mentions “various cubicles [afschutsels] that had been set up in the attic for his students.”

Sumowski Drawings, vol. 4, no. 857; and Amsterdam 2016, 120 – 21 (fig. 86).

Hofstede de Groot 1906, 86, no. 356.

See Sumowski Drawings, vol. 5, nos. 1250 – 58. For some reasonable concerns about the attributions of certain nude studies to Van Hoogstraten, see Giltaij 1988, no. 86; and Royalton-Kisch 2010, nos. 7 – 8.

Sumowski Drawings, vol. 5, no. 1254. See also Elen 1989, 238 – 39, no. 486; and Moscow 1995 – 96, 110, 286, no. 299.

Van Hoogstraten 1678, 294; translation from Brusati & Jacobs 2021, 322. See also Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 19; and Emmens 1979, 220.

See the entry for Barent Fabritius by I. Haberland in Turner 1996.