Choose a background colour

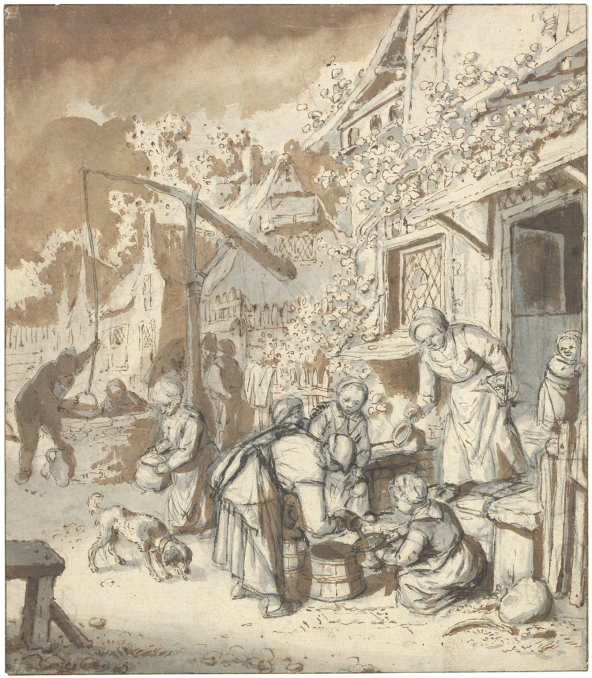

Cornelis Dusart, Dutch, 1660-1704: A Milk Seller Before a House or Inn, c. 1680-90

Pen and brown ink with gray wash over black chalk on paper; framing lines in black ink.

10 1⁄2 × 8 5⁄16 in. (26.6 × 21.1 cm)

Recto, lower left, pen and brown ink, inscription or signature trimmed away and no longer legible.

- Chain Lines:

- Horizontal, 24 – 25 mm.

- Watermark:

- Fragment showing a rampant lion, probably part of an Arms of Amsterdam, with full countermark PB.

- Provenance:

Bernard Houthakker, 1884 – 1963, Amsterdam (Lugt 1272, stamp on verso); his sale, Amsterdam, Sotheby Mak van Waay, 17 – 18 November 1975, lot 111; Jiles Boon, 1916 – 2009, Rhoon, Netherlands (Lugt 3355, stamp on verso); sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 16 Janurary 1985, lot 83; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.24.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Amsterdam 1964, no. 27, pl. 22.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.24

In this animated scene, a milk seller distributes her wares from one of the large buckets carried to the site on a wooden beam, now resting across her back. While the present customer eagerly awaits her portion, a young girl drinks her share from a pitcher to the rear. Two men discuss the day’s news and a toddler, aided by a matronly woman, descends the steps to join the excitement.

The image relates closely to Dusart’s earliest dated painting and bears a similar composition to a drawing by his teacher Adriaen van Ostade, who also explored the theme of peddlers-at-the-door in his work.

This animated scene depicts a woman selling milk in front of a house or inn. Having set down her two large buckets, she uses a smaller jug to distribute measured amounts of milk to her customers. She carried the buckets on the beam now resting across her back, which is designed to sit on her neck and shoulders. Cornelis Dusart packed nearly every corner of this drawing with his lively visual humor. The crouching girl watches her pot being filled with great earnestness, while another to the left attempts to sip her recently received share from an overly large pitcher. Seeing an opportunity, a dog in front of the bucket laps up a spill. He was originally accompanied by a cat (the ghostly outline of which can be seen in the black chalk underdrawing), but Dusart decided not to include him in the finished work. A matronly woman seated on the front steps aids a toddler navigating the steps, attracted to the excitement of the milk’s arrival. Rounding out the scene are two men with pipes discussing or disputing over some sheets of paper (perhaps the news), who obviously take no interest in the goings-on around the delivery of milk.

By Dusart’s day, milkmaids had already long served as popular subjects for Dutch artists.1

They often depicted them as young and attractive women, sometimes even sexualized, as one finds for example in the Archer and Milkmaid engraving by Jacques de Gheyn II (1565 – 1629).2

Other times, their role as objects of love interest can be more subtle or innocent, as seen in the iconic Milkmaid by Lucas van Leyden (1494 – 1533).3

Willem Buytewech (1591/92 – 1624) took a somewhat different approach, depicting a milkmaid from Edam as a means of displaying her local dress for a series of prints showing the regional fashions of young women from the rural working classes around Holland.4

Dusart’s milk carrier, on the other hand, appears more workaday in her patchy clothes, likely older, but in any case anonymous and seemingly innocuous.

This work relates closely to Dusart’s painting of the subject Fig. 63.1.

Cornelis Dusart, The Milk Seller, 1679. Oil on panel, 38.8 × 29.5 cm. Birmingham, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, inv. no. 49.8.

The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

While the drawing is undated, the painting bears the year 1679, making it one of the earliest known works by Dusart. He therefore painted it when he was only around nineteen years old, and just before he entered the guild in 1680. Eduard Trautscholdt surmised that the painting may have even been Dusart’s “masterpiece,” meaning (in the original sense of the term) the painting he submitted to prove his competence for admission into the guild as a master.5

The drawing is not strictly preparatory in nature, but it does reveal the enduring influence of his teacher, Adriaen van Ostade (1610 – 1685), as it follows Van Ostade’s own drawing of the subject from somewhat earlier Fig. 63.2.6

Adriaen van Ostade (probably retouched by Cornelis Dusart), The Milk Seller, c. 1660– 70. Pen and brown ink, with gray and brown washes over graphite on paper, 238 × 208 mm. Paris, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, inv. no. 2145.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Bernhard Schnackenburg pointed out that Dusart probably retouched Van Ostade’s drawing, adding washes and perhaps reinforcing some of the lines, something Dusart did to a number of Van Ostade’s drawings after the latter’s death in 1685.7

Van Ostade was still alive, however, when Dusart drew the present sheet, if it indeed dates to around the same time he made the painting. One assumes that Dusart would have had easy access to Van Ostade’s drawing while still attendant in his master’s workshop around 1679. Dusart borrowed the basic composition of Van Ostade’s drawing, including the primary motif of the bent-over milkmaid, as well as a number of his auxiliary figures, such as the crouching girl receiving her milk, the dog, and the toddler descending the steps. For his painting, however, Dusart changed several members of this cast of characters, but retained his own invention of the girl with the jug to the left, accompanied by what appears to be a younger sibling. Ultimately, both the drawing and painting by Dusart pay homage to Van Ostade’s take on the milkmaid as subject matter, celebrating the salubrious nature of village life in a lighthearted fashion, and further exploring the peddlers-at-the-door theme that both artists took up in a great number of their works.

End Notes

For overviews of the milkmaid in Dutch art, see especially New York 2009a, discussing Vermeer’s famous painting of the same name, which, it should be noted, does not actually depict a milkmaid or dairy worker but rather an urban kitchen servant; as well as G. Luijten in Amsterdam 1997, 260 – 63, no. 52.

Andries Stock, after Jacques de Gheyn II, Archer and Milkmaid, engraving, 413 × 329 mm; see W. Liedtke in New York 2009a, 15; G. Luijten in Amsterdam 1997, 129 – 32, no. 21; and (for the related drawing) Robinson 2016, 145 – 47, no. 40.

New Hollstein (Lucas van Leyden), no. 158; Washington & Boston 1983, 88 – 89, no. 26; and I. M. Veldman in Leiden 2011, 247, no. 46. Closer to Dusart’s time is a painting attributed to Nicolaes Maes (Rustic Lovers, c. 1658 – 59, oil on wood, 69.8 × 90.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv. no. 485), for which see W. Liedtke in New York 2009a, 11.

Gillis van Scheyndel after Willem Buytewech, Woman from Edam, engraving, 195 × 140 mm; see Haverkamp-Begemann 1959, 187, no. CP4.

Trautscholdt 1966, 176 – 77.

Schnackenburg 1981, 107, no. 132.

Schnackenburg 1981, 107, no. 132. For Dusart’s retouching of Van Ostade’s drawings generally, see Schnackenburg 1981, 60 – 61; and Anderson 2015. Most of the retouchings probably took place after Dusart inherited Van Ostade’s studio remains in 1685.