Choose a background colour

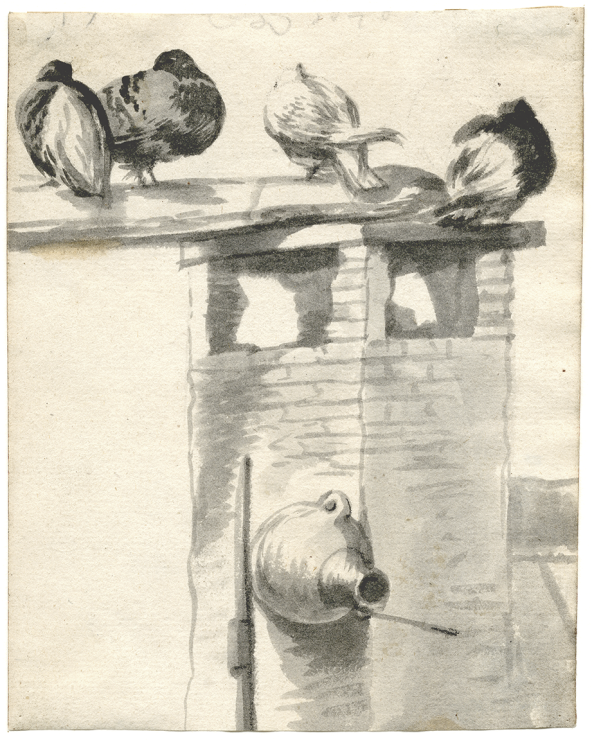

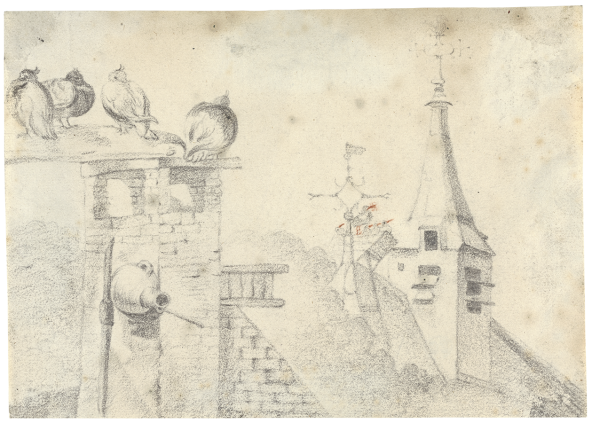

Cornelis Saftleven, Dutch, 1607-1681: Pigeons on a Chimney and a Nest of Storks by a Steeple, c. 1646

Black chalk and gray wash with touches of red chalk (for the beaks of the storks) on paper; framing lines in black ink.

5 5⁄8 × 7 11⁄16 in. (14.3 × 19.5 cm)

Recto, upper left in pencil, 16.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 22 – 24 mm.

- Watermark:

- Fragment of a Crown, likely the top of an Arms of the Seven Provinces with Lion.

- Provenance:

Hans van Leeuwen, 1911 – 2010, Amerongen (Lugt 2799a, stamp on verso); his sale, Christie’s, Amsterdam, 24 November 1992, lot 174; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.76.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Schulz 1978, 164, no. 392; F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 90 – 91, no. 28.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.76

Four plump pigeons rest on a chimney above a suspended clay pot, a probable nesting site for smaller birds. In the middle distance a family of storks, portrayed with distinctive red chalk beaks, roost in a nest made specifically for them. Such man-made nesting boxes were installed to entice these long-legged wading birds because they allegedly conferred luck and fertility to a home’s inhabitants, though the property here is a church or civic building.

Cornelis Saftleven’s creativity and originality are apparent from the drawing’s unusual viewpoint and unexpected subject matter. To satisfy demand among collectors for his work, Saftleven occasionally copied his own drawings, including this sheet, which he reproduced from a larger composition.

This unusual viewpoint across rooftops demonstrates Saftleven’s originality in both his compositional approach and choice of subject matter. Wolfgang Schulz catalogued this drawing under landscapes, though it defies the norms of that genre, being a study of birds in their natural milieu drawn from what appears to be a high vantage point.1

Birds frequently feature in Saftleven’s paintings and drawings, often in his satires and sometimes in his more focused studies of individual animals. Here he depicts four plump pigeons on a chimney above a suspended clay pot that is probably a nesting site for smaller birds like starlings. A group of storks in the middle distance appear in a nest built specifically to entice them to settle there, as is still seen in parts of the Alsace and elsewhere today. The origins of the long-standing practice of building stork nests on rooftops is unclear, but has been related to the conviction that storks bring good luck to the inhabitants, as well as the notion of increased fertility (thus the myth of storks bringing babies). In this case, however, the storks nest on a church or civic structure of some sort rather than a domestic dwelling.2

Two other drawings by Saftleven reproduce the left and right halves of this composition, in Leiden and Paris respectively Fig. 27.1,Fig. 27.2.3

Cornelis Saftleven, Pigeons Sitting on a Chimney, 164[6]. Brush in black and gray ink, 118 × 93 mm. Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, inv. no. pk-t-aw-1899.

Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden

Cornelis Saftleven, Storks in a Nest on a Church, 1646. Black chalk, brush in black and gray ink, 145 × 93 mm. Paris, Fondation Custodia, inv. no. 4970.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Schulz was correct in accepting all three as autograph works by the artist, though he left open the question of precedence. Given the looser appearance of the Leiden and Paris sheets, they were arguably generated before the present work, which appears to combine their subjects into one composition. Saftleven unified the bank of trees in the background, and made subtle additions in red chalk for the beaks of the storks. Since the two halves are to scale with the Peck sheet (though the Leiden half was cut down a little more), it is possible they were once part of a single larger sheet that was sliced in two. Each half bears Saftleven’s monogram (both accepted as autograph by Schulz), and one or both of these may have been added by the artist if he cut the sheet in half himself. The monogram and date on the Leiden sheet have been cropped through the middle, making the last digit illegible, but the year is most likely the same as the visible one on the Paris half, 1646. The present drawing is assumed to be an autograph copy made around the same time or shortly thereafter.

As Schulz pointed out, Saftleven was occasionally in the habit of making copies of his drawings, a testament to the demand they must have had among collectors.4

One of the best documented examples is a study of a brown bear that survives in four different versions, each with slight differences, and all dated 1649.5

In another notable case, Cornelis, who lived in Rotterdam, sent his brother Herman in Utrecht a remarkably faithful replica of his 1662 study of a seated man with a pipe.6

This sheet, recently acquired by the Rijksmuseum, was once folded to enclose a letter and bears Herman’s address of the verso. It serves as proof that not all of Cornelis’s drawn copies were necessarily made for the market, though it was nevertheless the most likely motivating factor in other cases.

Schulz noted a copy of this drawing from the Hofstede de Groot and Houthakker collections once on the art market (and then attributed to Herman Saftleven) that he suspected to be by a later hand.7

Now in the Ackland’s collection, it was acquired and donated by the Pecks for study purposes Fig. 27.3.

Unidentified artist, copy after Cornelis Saftleven, Pigeons on a Chimney and a Nest of Storks by a Steeple, c. 1700 – 50. Black and red chalk with gray wash on paper, 143 × 195 mm. Chapel Hill, Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.131.

The handling is indeed indicative of a copy by another artist (who remains unknown), and the paper bears a watermark from the early eighteenth century.

End Notes

Schulz 1978, 164, no. 392.

Warren-Chadd & Taylor 2016, 22 – 23.

For the drawing in Leiden, see Schulz 1978, 171, no. 424; and for that in Paris, idem, 174, no. 440.

Schulz 1978, 60.

Schulz 1978, nos. 239 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), 251 (Amsterdam, Fodor Collection, Amsterdam Museum), 285 (Boston, Abrams Collection), and 350 (whereabouts unknown); see also the entries by W. Robinson in Amsterdam, Vienna, New York & Cambridge 1991 – 92, 160 – 61, no. 71; and B. Broos in Schapelhouman & Broos 1993, 154, no. 115.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-t2019-423; see Zwollo 1987. The original 1662 drawing is also in the Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-t-1989-104.

Schulz 1978, 164, under no. 392; also mentioned by F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 90 – 91, no. 28.