Choose a background colour

Abraham Bloemaert, Dutch, 1566-1651

:

Studies of Putti, c. 1590-1600

Pen and brown ink and brown wash on paper; framing lines in brown ink

11 7⁄16 × 15 3⁄8 in. (29.1 × 39 cm)

Recto, lower center in pen and ink (by the artist), ABloemaert; lower right in pen and ink (by another hand), Bloemaert fecit.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 24 – 25 mm

- Watermark:

- None

- Provenance:

Possibly Samuel van Huls; his sale, Swart, The Hague, 14 May 1736, under no. 404 (2 feuilles avec des Enfans) or no. 472 (…& une feuillet avec des petits Enfans); sale, Van de Schley & De Winter, Amsterdam, 16 September 1760, no. 65 (Een Plafond met Kindertjes…met de pen en roed en wit gehoogt) or no. 66 (Een dito…); G. and W. van Berckel; their sale, De Leth, Amsterdam 24 March 1761, album B, no. 17 (Een Hemel met een meenigte van biddende Kindertjes…); possibly sale, De Winter & Yver, Amsterdam, 19 November 1764, album G, no. 585 (Een Glorie van Engelen met de Pen en met Omber gewassen); M. Oudaan; his sale, Bosch & Arrenberg, Rotterdam, 3 November 1766, album E, no. 115 (Een Hemeltje…); dealer, Broekma, Amsterdam, 1954; Hans van Leeuwen, 1911 – 2010, Amerongen (Lugt 2799a, stamp on backing sheet, removed); his sale, Christie’s, Amsterdam, 24 November 1992, lot 18; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.7

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Arnhem 1958, no. 15; Utrecht 1959, 5, no. 7; Laren 1963, 3, no. 14; Nijmegen 1965, 9, no. 4; Leeuwarden 1966, no. 2; Bonn 1968, 13, no. 16; Rheydt 1971, no. 7; Amsterdam 1975, 16, no. 14; Utrecht 1978, 12, no. 14; Bremen 1979, no. 13; Braunschweig 1980, no. 13; Freiburg 1982, no. 9; Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 407, under no. T107; Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 342 – 43, no. 1062, vol. 2, 375, pl. 1062.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.7

This dynamic sheet features nude babies, or putti, that twist, turn, fly, and tumble in all directions. It is the largest and most involved drawing of putti to survive by Abraham Bloemaert and was part of his atelier thesaurus, a model book of motifs he kept in his workshop for later use. It served as source material for the artist and his many students and assistants and remained in his studio for about fifty years. Such putti appeared regularly in Bloemaert’s Adoration and Annunciation scenes painted for his Catholic patrons in Utrecht.

Conservation treatment to remove old backing paper revealed previously unknown sketches. The two drawings of putti resting on coats of arms are initial designs for a title page in Bloemaert’s Tekenboek (Drawing Book), a compilation of motifs for artists published in numerous editions into the eighteenth century.

This exuberant outpouring of putti is one of the most dynamic and entertaining drawings to come from the hand of Abraham Bloemaert. The putti fly or fall in a joyous jumble with varying degrees of concerted action, but generally without any specific sense of direction. Given the image’s centrifugal energy and nearly uniform field of figures, it makes sense that an eighteenth-century auction house cataloguer once described this sheet as “A ceiling with little children” (Een Plafond met Kindertjes).1

One might indeed assume that it was a design for a Baroque-era trompe-l’oeil ceiling painting filled with putti, though no such work by Bloemaert is known to have existed. He did occasionally execute architectural painting commissions, but more likely this drawing was a study sheet of the type that he kept in the studio as part of his atelier thesaurus, or model book for his and his pupils’ use. Bloemaert even included a section on putti in his famous compendium for artists, the Tekenboek (Drawing Book). None of the twelve plates in that publication are as large or contain nearly as many figures as in the present sheet, though a few do adapt some of the poses seen here.2

Putti were an important motif for a Catholic artist like Bloemaert. He frequently included them in various Adoration and Annunciation scenes, and they appear as well in other subjects in both his paintings and print designs.3

As for his drawings, only a small handful of his studies of putti survive, none so large or involved as this, and none with figures that can be directly related to those in his paintings.4

Nevertheless, he still had plenty of opportunities to deploy various putti in his artworks throughout his career, both in his hometown of Utrecht, which still had a large Catholic population after the Protestant-led Dutch Revolt (1568 – 1648), and elsewhere in the country. Many of his putti-filled paintings were made for the schuilkerken, or clandestine churches for Catholic services (often based in private homes) that dotted Utrecht and other cities in the Netherlands.5

One does not otherwise often encounter a “glory” of putti like this in Dutch art, though Rembrandt’s famous etching of the Annunciation to the Shepherds from 1634 is a notable exception.6

In preparation for the present exhibition, conservator Grace White removed an old backing paper onto which this drawing had been mounted, revealing some new, previously unpublished sketches on the verso Fig. 2.1.

Abraham Bloemaert, Sketches on the verso of no. 2017.1.7 [detail], c. 1648 – 50. Pen and ink, black chalk, and brush in brown and gray inks.

The two sketches of putti with coats-of-arms appear to be initial designs, or primi pensieri, of titlepages for Bloemaert’s Tekenboek. The two putti holding a coat-of-arms surrounded by two circles was used as a frontispiece for Part Six of the Tekenboek, which treats figures and figure groups (rather than the section treating putti, which actually appears as Part Five with a different frontispiece) Fig. 2.2.7

Frederick Bloemaert, after Abraham Bloemaert, Title-page for Part VI of the Tekenboek, c. 1650. Engraving, 205 × 158 mm.

A related drawing appears in the so-called Cambridge Album, a collection of drawings by either Abraham or his son Frederick, used as preparatory studies for the engraved plates of the Tekenboek Fig. 2.3.8

Abraham or Frederick Bloemaert, Preparatory for the title-page of Part VI of the Tekenboek (Cambridge Album no. 121), c. 1648 – 50. Pen and ink, and black and red chalk. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. no. pd.166-1963.f.125.

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

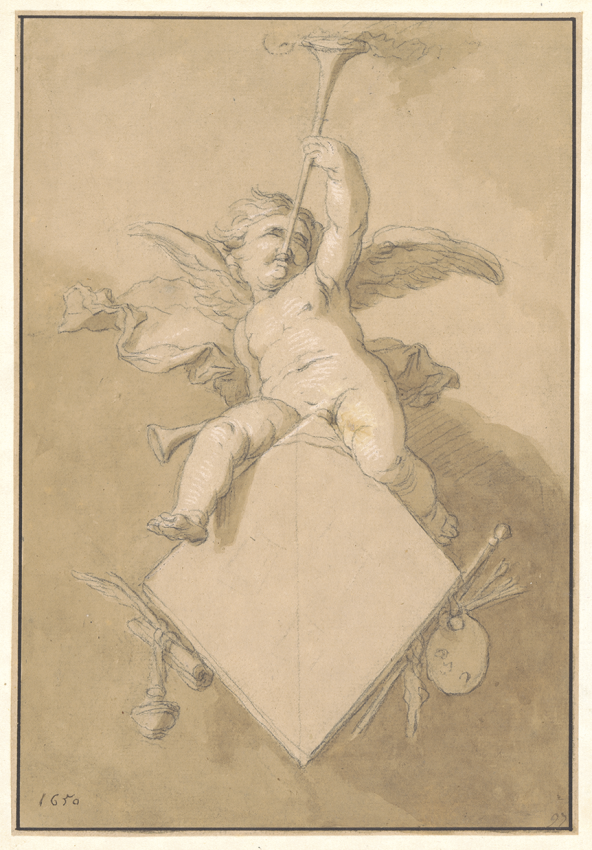

In this intermediate drawing, the design is further developed and inscribed with the shield shape that was eventually published. The single figure of a putto blowing a horn on the verso reappears in a more finished drawing bearing the date 1650 in the Cambridge Album Fig. 2.4.9

Abraham or Frederick Bloemaert, Unused title-page design, probably for the Tekenboek (Cambridge Album no. 97), 1650. Pen and ink with washes. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. no. pd.166-1963.f.101.

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

It remained unused in the Tekenboek, though it could have been an idea for a frontispiece design.

The coat-of-arms with the three blank shields constitutes the blazon of the Guild of St. Luke, the traditional painters’ guild. The symbol likely originated from the tradition of painters (schilders) decorating medieval heraldic shields (schilden).10

Bloemaert must have taken particular pride in this emblem of the guild, since he was one of the founding members of Utrecht’s own Guild of St. Luke in 1611, and was its dean in 1618.11

Bloemaert also drew a few other frontispiece designs using the guild’s coat-of-arms, obviously an important emblem for the famous painter and educator.12

Significantly, these sketches demonstrate that this sheet remained in the artist’s possession over the greater course of his career, from the early 1590s when he drew the masterful mass of putti on the recto and signed it, until the late 1640s, when preparations began for the publication of the Tekenboek. The verso seems to have been casually used for the sketches, no doubt with the putti on the recto serving as inspiration for the subject at hand, though no single putto seems to correspond exactly. The strong vertical-running centerfold is likely indicative of it being stored in an album during its time in the workshop. Of the two other sketches on the verso, the one “reclining” putto in between the two coats-of-arms does appear to be by Bloemaert’s hand. The other one (a flying putto, not visible in Fig. 2.1) is simply traced through from a figure on the recto, though with a few additions, making it difficult to say whether this is the work of the master as well.

End Notes

Sale, Van de Schley & De Winter, Amsterdam, 16 September 1760 (see under Provenance, above).

For putti in the Tekenboek, see Bloemaert 1740, pls. 107 – 18; Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, nos. T107 – T118.

For remarks on Bloemaert’s uses of putti generally, see Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 407, under no. T107.

Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 342 – 45, vol. 2, 374 – 77, nos. 1060 – 72.

For Bloemaert’s commissions for the schuilkerken, see Van Eck 2008, 19 – 49; and Nogrady 2009, 181 – 220.

Bartsch, no. 44; and New Hollstein (Rembrandt), no. 125.

Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, no. T119.

Bolten 2007, no. 1270. For some reason, the final engraved design does not appear in the rare, early printings of the Tekenboek from circa 1650, though it does in the Visscher edition from circa 1685; see Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 388, under no. 1270 for the list of editions in which it appears. For the complicated printing history of the Tekenboek generally, see Bolten 2017b, 50, 52 (note 7).

Bolten 2007, no. 1246.

For the coat-of-arms of the Guild of St. Luke (related to a set of designs made for the Haarlem guild chapter in 1631), see Taverne 1972 – 73, 67 – 69.

For Bloemaert and the guild, see Roethlisberger & Bok, vol. 1, 570, 581. Bloemaert was removed from his position as dean in 1618 during the dramatic, widespread purge instituted by the Prince of Orange of all civic positions by anyone who did not profess hard-line Calvinist (specifically CounterRemonstrant) sympathies, which affected a number of Protestants in such roles, and certainly all Catholics such as Bloemaert. His son, Hendrick, would later serve as dean of the guild in 1643, after regulations relaxed around having Catholics in such positions.

See, for example, Bolten 2007, nos. 628 (c. 1648 – 50), 633 (dated 1647), and 1066.