Choose a background colour

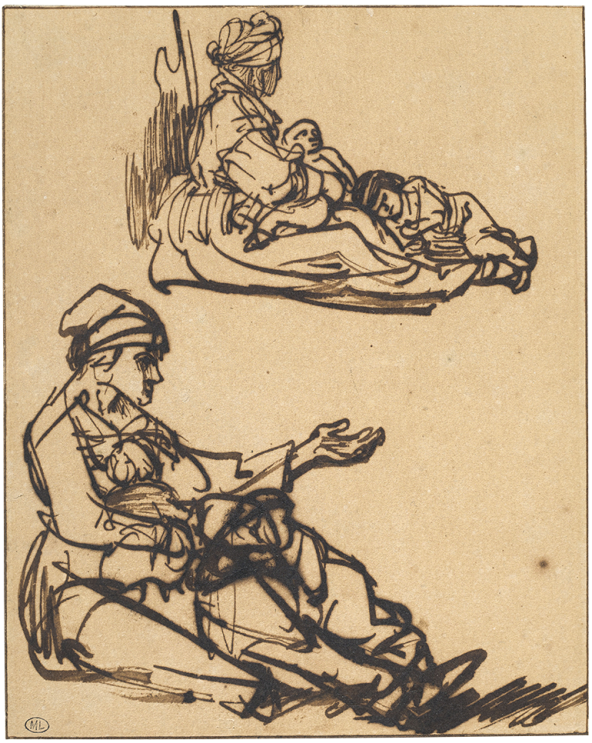

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669: Studies of Women and Children, c. 1640

Pen and brown ink with brush or finger smudging on paper; framing lines in brown ink

5 3⁄8 × 5 3⁄16 in. (13.6 × 13.2 cm)

Recto, by the artist in pen and ink, een kindeken met een oudt jack op sijn hoofdken (a little child with an old jacket on his head); and in graphite, upper left, by a later hand, 30.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 22 – 23 mm

- Watermark:

- Strasbourg Lily, with letters PR below, fragment showing all but the crown. Identical to that in another drawing by Rembrandt, cf. Schatborn 1985, 237, no. 27. Similar to Hinterding 2006, variant C’.b.; Ash & Fletcher 1998, variant E’.a

- Provenance:

Christian David Ginsburg, 1831 – 1914, Palmer’s Green (Lugt 1145, mark on verso); Sotheby’s, London, 29 July 1924, lot 26; Victor Koch, active c. 1919 – 1946, London; dealer, Heinrich Eisemann, 1890– 1972, Frankfurt and London; Stefan Zweig, 1881 – 1942, Vienna, London, and Rio de Janiero; Alfred Zweig, 1880 – 1977, New York; sale, Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, 30 May 1979, lot 81; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, 2017, inv. no. 2017.1.64.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Benesch 1954– 57, vol. 2 (1954), 73, no. 300, fi g. 340; Benesch 1973, vol. 2, 76 – 77, no. 300, fi g. 366; Strauss & Van der Meulen 1979, 605; Cambridge 1980, no. 15; Vogel-Köhn 1981, 54, 221, no. 51; Kitson 1982, fi g. 21; Cambridge 1983; Kitson 1992, fi g. 20; Amsterdam 1999, 86; Tümpel 2003, 171 (note 1); Peck 2003, 26 – 29, no. 5; C. S. Ackley in Boston & Chicago 2003 – 04, 169 – 72, 321, no. 100; Schatborn & Dudok van Heel 2011, 349, no. IX, fi g. 159; Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 229, no. D344.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.64

Quick, confident pen strokes applied with pen and ink demonstrate Rembrandt’s unparalleled ability to capture the essence of his subjects’ features, body language, and emotional state with just a few lines. Observed from life, this study of women and children bears an inscription by the artist, one of about seventeen extant drawings known today. It says, “a little child with an old jacket on his head,” apparently a noteworthy detail for Rembrandt. Remnants of a third sketch along the upper edge, which perhaps repeated the seated woman and infant motif, indicate these studies once belonged to a larger sheet.

This is one of a handful of Rembrandt’s charming drawings of women and children observed from life, rendered with a keen eye for character, behavior, and movement.1

The woman on the right appears to be warily eyeing something or someone while gently pulling along a toddler who slightly protests the forced movement. The blasé infant on the left, however, rests at ease, cradled in the arms of a woman who appears to be seated. Rembrandt brilliantly suggested this woman’s lower legs with his finger (or perhaps a dry brush) dipped in an overloaded passage of ink and swiftly swiped along the paper.

His inscription records a detail that he either found amusing or worth remembering about the infant’s head covering: “a little child with an old jacket on his head” (een kindeken met een oudt jack op sijn hoofdken). By “jacket” (jack or jak), he probably meant a small child’s overcoat, or what today would be called a manteltje. Rembrandt was occasionally in the habit of inscribing his own drawings with similar remarks, though only about seventeen such sheets survive, and most of these inscriptions appear on his history subjects.2

This is the only genre scene with women and children he inscribed, and the last of his known drawings inscribed by own hand to reach a public collection. He obviously added the inscription after both figure groups were finished, to judge from its exact placement between them. Because the inscription is autograph (clearly matching the orthography of his established handwriting), the Peck sheet has been designated as a “core work,” one of the drawings indisputably by Rembrandt. These can be useful for scholars attempting to evaluate the sometimes difficult to determine attributions of other drawings that may or may not be by him.3

The tangle of lines along the upper edge indicates that it was cut from a larger sheet at some point, but a match for the missing portion has yet to come to light. It is possible that it repeats the motif of the woman cradling the infant in her arms, reflective of Rembrandt’s tendency to sometimes offer the same subject with a different aspect or from a different angle in his sketches.4

An example from the same period, a drawing of a begging mother with her children, is in the Louvre Fig. 17.1.

Rembrandt, Two Studies of a Seated Beggar Woman with Two Children, c. 1639. Pen and brown ink on paper, 175 × 140 mm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. no. 22965.

RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

He used a similarly heavy iron-gall ink, which tends to seep into the paper over time and make the lines seem thicker than they originally appeared.

While a few dozen of Rembrandt’s studies of women and children survive, there must have been many more. One of the most avid collectors of Rembrandt’s drawings in the seventeenth century was the artist Jan van de Cappelle (1624 – 1679), whose inventory drawn up in 1680 contained a portfolio “with 135 drawings of the life of women with children by Rembrandt.”5

He probably obtained these during the sales in 1657 – 58 brought about by Rembrandt’s bankruptcy, along with a large number of other drawings by the artist that later turned up in Van de Cappelle’s collection.6

It is entirely possible that the present drawing once belonged to the album mentioned in Van de Cappelle’s inventory.

Most of Rembrandt’s drawings featuring women and children date to the late 1630s or early 1640s. As scholars have long noted, Rembrandt’s wife Saskia bore four children in these years, a fact which presumably spurred his interest in the subject matter. Sadly, though not entirely uncommon for the era, their first three children did not survive infancy. Rumbartus was born in December 1635 and buried two months later. Two daughters named Cornelia (born in 1638 and 1640) only survived for about two weeks each. Only their fourth child, Titus (1641 – 1668), survived into adulthood.7

In later years, with his partner Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt had a daughter who also survived into adulthood who was also named Cornelia (1654 – 1684). Given Rembrandt’s penchant for depicting his wife Saskia in various paintings, drawings, and prints before her death in 1642, earlier scholars were understandably tempted to posit the identity of some of the children in Rembrandt’s drawings from circa 1635 to 1645 as his own.8

As other scholars have pointed out, however, this practice proves difficult to reconcile with the presumed dates of a number of drawings, including this one, which he likely made before Titus’s birth in 1641, and in which the children appear to be too old to have been either Rumbartus or the two infants named Cornelia.9

Rembrandt’s inscription, in any case, should also give us pause about the urge to identify the children in this and other works as family members or known acquaintances. He labeled the infant here anonymously as simply a kindeken. It is far more likely that these women and children were unknown to him, observed with artistic interest on the streets around him. That he made this drawing during a period of emotionally affecting and undoubtedly grief-filled early fatherhood is all the more remarkable. Otto Benesch dated this drawing circa 1636 on stylistic grounds, but more recent scholarship has tended to push it more toward the end of the decade, to circa 1639 – 40.10

The Peck drawing has the rare distinction of bearing the same watermark found in another Rembrandt drawing, Three Women and a Child in the Rijksmuseum, an exact match confirmed by recent technical analysis Fig. 17.2.11

Rembrandt, Three Women and a Child by a Door to a House, c. 1640. Pen and brown ink on paper, 233 × 178 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-t-1889-a-2056.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

It is certainly possible that Rembrandt used sheets from the same ream of paper years apart, but more likely, and especially given the large amount of paper he obviously used on a day-to-day basis, these two drawings were made around the same time. Peter Schatborn originally put the Rijksmuseum sheet in the mid-1640s, but more recently assigned it a reconsidered date of circa 1640 on stylistic grounds, which happens to be more in keeping with the conjectured date range of this drawing as well.12

End Notes

For Rembrandt’s drawings with women and children, see Vogel-Köhn 1981; Edinburgh & London 2001, passim; P. Schatborn in Paris 2006 – 07, 14 – 16; and Slive 2009, 80 – 89.

For the three-part “Core List” of Rembrandt’s drawings, see Schatborn 2011a; Royalton-Kisch & Schatborn 2011; and Schatborn & Dudok van Heel 2011. For the present drawing, see idem, 349, no. IX. For an orthographic analysis of Rembrandt’s inscription on this work, see Royalton-Kisch, Benesch Online, no. 300, 8 November 2016 (accessed 22 December 2021).

For the suggestion that the missing fragment repeats the motif, see Peck 2003, 26; and C. S. Ackley in Boston & Chicago 2003 – 04, 172.

Bredius 1892, 37: “No. 17. Een dito [portfolio] daerin sijn 135 tekeningen sijnde het vrouwenleven met kinderen van Rembrant.”

Schatborn 1981, 10 – 12.

Bikker 2019, 70 – 71, 77, 208.

Slive 2019, 14.

See, for example, F. Stampfle in Turner 2006, 139 – 40, no. 211; and J. Lloyd Williams in Edinburgh & London 2001, 134, no. 53. It has been pointed out that Rembrandt would have been familiar with the several children of his former employer, Hendrick Uylenburgh, in these years (see Amsterdam 1984 – 85, 8), though the notion that his drawings might depict them seems too speculative.

Vogel-Köhn 1981, 221, no. 51 (c. 1639 – 40); Peck 2003, 26 – 29, no. 5 (c. 1640); and Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 229, no. D344 (c. 1639).

Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 235, no. D362; and Schatborn 1985, 62 – 63, no. 27. For the watermark, see idem, 237, no. 27. My thanks to Charles R. Johnson for confirming the match using MAWI software.

Schatborn 1985, 62 – 63, no. 27 (mid1640s); and Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 235, no. D362 (c. 1640).