Choose a background colour

Nicolaes Berchem, Dutch, 1620-1683

:

Travelers in an Italian Landscape, 1655

Brush and brown and gray ink of various shades over a counterproof in black chalk on paper; framing lines in brown ink.

5 11⁄16 × 9 1⁄16 in. (14.5 × 23 cm)

Recto, signed and dated by the artist in brush and brown ink, upper left, CBerghem.f. 1655; verso, lower left, in pen and ink, N:885 (in the hand of Goll van Franckenstein); and lower left, in pencil, N. Berchem / v.icoe / hoog 5½ / breed 8¾ / 330.

- Chain Lines:

- Horizontal, 25 mm.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Sybrand Feitama II, 1694 – 1758, Amsterdam, his Notitie der Tekeningen, 1746: 1 Ezel, enz.: tot een Weerga van’t vorige, mede Ao 1655 met roet geteekend; his sale, 1758, Album C, no. 10: Een Landschaft met differente Beesten, waarin op den Voorgrond is een Vrouw rydende op een Ezel, met roet gewasschen 1655, naderhand in’t koper gebragt door J. Visscher, h. 5 br. 9 d (to De Leth for f 109); Cornelis Ploos van Amstel, 1726 – 1798, Amsterdam; his sale, 1800, Album F, no. 10 (to Tiedeman for f 300); Johann Goll van Franckenstein, 1722 – 1785, Amsterdam (Lugt 2987, his inv. no. on verso); by descent, Johan Goll van Franckenstein, 1750 – 1821, Amsterdam; by descent, Pieter Hendrick Goll van Franckenstein, 1787 – 1832, Amsterdam; his sale, Amsterdam, De Vries, Roos and others, 1 July 1833, Album U, no. 3 (to De Vries for f 140); possibly Jan Gijsbert Verstolk van Soelen, 1776 – 1845, The Hague (Lugt 2490); possibly his sale, De Vries, Brondgeest, and Roos, Amsterdam, 22 March 1847 and following days, Album A, no. 72 (to Leembruggen for f 300); John Postle Heseltine, 1843 – 1929, London (Lugt 1507); Jean Theodore Chênevert, b. 1911, Limburg; sale, Sotheby’s, Amsterdam, 4 November 2003, lot. 106 (as Follower of Nicolaes Berchem, possibly Abraham Begeyn); dealer, Christina van Marle, 2011; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.3.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

London 1917, no. 1; Fucci 2022b.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.3

Accompanied by a group of herders and their livestock, a mounted shepherdess points to an immense landscape vista in the distance. Such Italianate views were extremely popular in the Netherlands, produced by artists whether they had traveled south of the Alps or not. It is unlikely that Nicolaes Berchem, who specialized in these scenes, ever went to Italy, but rather borrowed his subject matter from artist colleagues who did.

Related to one of Berchem’s famous paintings and a black chalk drawing prototype, this work was made using a counterproof. The artist placed a blank sheet on the drawn prototype, pressing firmly to transfer some of the chalk lines. This process made a reproduction in reverse. Berchem then skillfully applied tonal gradations of wash to model the figures, creating a highly finished drawing likely intended for the market.

This lively composition centers on a group of herders as they drive their livestock through a vast panoramic landscape. Such scenes helped define Nicolaes Berchem as one of the leading artists of his generation specializing in Italianate landscapes that often feature, as here, the idealized, bucolic lives of roaming shepherds and shepherdesses.1

The question of whether Berchem ever traveled to Italy has been subject to debate, but recent scholarly consensus squarely dismisses such a trip.2

Instead, Berchem seems to have adduced his Italianate style from artist colleagues who made the journey south, and who often continued to produce such subject matter upon returning to the Netherlands. Italianate paintings were in great demand back home and frequently achieved high prices in the seventeenth century.3

Berchem’s works were not only popular in his lifetime, but even more so in the eighteenth century, when he was esteemed (along with Rembrandt) as one of the greatest Dutch artists of the preceding age.4

This drawing is closely related to one of Berchem’s most celebrated paintings, Italian Landscape with Figures and Animals in the British Royal Collection Fig. 44.1.5

Nicolaes Berchem, Italian Landscape with Figures and Animals, 1655. Oil on panel, 32.8 × 44.1 cm. Windsor, Collection of Her Majesty The Queen, inv. no. RCIN 404818.

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

The riding shepherdess who gestures or points remained one of Berchem’s favorite motifs throughout his career.6

His shepherdesses always rode sidesaddle (though it is not immediately apparent from this angle) and required different artistic considerations in terms of fulcrum and balance in their poses than male riders. Both the drawing and the painting are signed and dated 1655, but the drawing shows the composition in reverse and is more focused on the central figure group. The Peck drawing and the painting in Windsor derive from a common prototype, a much simpler black chalk and wash drawing that he signed and dated the year before in 1654 Fig. 44.2.7

Nicolaes Berchem, Travelers in an Italian Landscape, 1654. Black chalk and gray washes on paper, 146 × 226 mm. Present whereabouts unknown.

Artokoloro/Alamy Stock Photo

As Annemarie Stefes first realized, the Peck drawing was developed from a counterproof of this latter work.8

To make a counterproof, an artist places a blank sheet on top of the drawing and rubs it firmly (or uses a press) to create an offset image. This transfers enough chalk to create a reproduction in reverse of the original. The counterproof is necessarily fainter in appearance, though it could be worked into a more finished drawing by applying further media by hand, as was the case here.

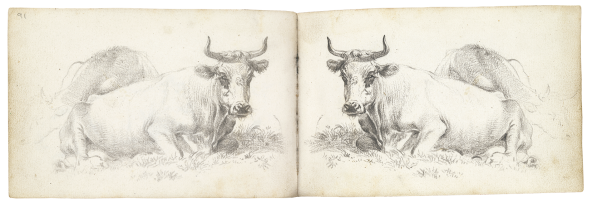

We know that Berchem made counterproofs previously from several examples found on the facing pages of his early sketchbook of animal studies from circa 1644 in the British Museum Fig. 44.3.9

Nicolaes Berchem, Resting Cow, from the London sketchbook, c. 1644 – 45. Black chalk on paper with counterproof on facing page, each leaf 96 × 150 mm. London, British Museum, inv. no. 1920,0213.2.

The Trustees of the British Museum

He used some of these studies for a series of etchings. Berchem’s likely motivation, in this case, was to create drawings in reverse that would aid in the preparation of the plates since the resulting printed image would then appear in the same direction as the original sketch.10

What is unusual about the Peck drawing, and fascinating for our understanding of historical processes, is that Berchem appears to have made this counterproof as the basis for creating a finished version (one that he signed and dated) that could be sold as a work of art in its own right. It is the only known case of a signed or otherwise highly finished autograph replica made with the assistance of a counterproof in his oeuvre that has thus far come to light.11

This practice is more frequently encountered in the eighteenth century when artists produced counterproofs of their drawings to generate a second version for sale, or to preserve one for studio use.12

In the present work, Berchem started with a counterproof of the black chalk lines, still visible beneath the wash, that line up exactly with the 1654 drawing when overlaid digitally in reverse. He then extensively applied washes with great attention to detail, creating tactile volumes and a sense of directional light. The subtle handling of the wash is quite exceptional in certain passages, such as in the clothing of the woman and her companion, where Berchem employed at least four gradations of tone to carefully model the figures. Such skill strongly suggests Berchem’s own hand rather than that of a follower such as Abraham Begeyn (1637 – 1697), an attribution suggested when the drawing appeared at auction in 2003, before its status as a reworked counterproof by Berchem himself was noted by Stefes.13

A copy of the original 1654 drawing was used by Jan de Visscher (1633/34 – 1712) to make an etching of the composition Fig. 44.4.14

Jan de Visscher, Travelers in an Italian Landscape, in or after 1656. Etching on paper, 157 × 234 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv. no. RP-P-OB-61.954.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Visscher made more prints after Berchem’s designs than any other printmaker and probably worked at Berchem’s behest despite the fact that Berchem himself was an adept etcher.15

There is one small but distinct change in the composition that distinguishes the Peck drawing from the 1654 prototype and Visscher’s etching based on it: the dog in the foreground following behind the shepherdess has turned his head to face the viewer. One can still detect a faint ghosting of the original black chalk lines from the counterproof that show his snout facing forward, but Berchem cleverly reworked this one spot to give the hound a slight twist of the head. He possibly sought to make a subtle improvement to the composition, or perhaps just wanted to add a playful note of variation to a successful design that he clearly considered worthy of repeated use.

End Notes

For Berchem’s life, see P. Biesboer in Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 11 – 35; and I. van Thiel-Stroman in Biesboer et al. 2006, 102 – 05. For his drawings, see especially Stefes 1997 (with a catalogue); P. Schatborn in Amsterdam 2001, 187 – 95; and A. Stefes in Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 97 – 115.

For an overview of the issue, see P. Biesboer in Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 21 – 24. Serious doubts about a presumed trip to Italy were first put forward in Stefes 1997, 47 – 48.

For the market for Italianate landscape painting in the Netherlands, see A. Chong in Amsterdam, Boston & Philadelphia 1987 – 88, 114 – 18.

G. Seelig in Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 59 – 69.

White 2015, 97 – 98, no. 20; and Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 41, 138, no. 18 (and cover image).

See, for example, Mountainous Landscape with Shepherds and Cattle from circa 1670 to 1675, also in the British Royal Collection (inv. no. RCIN 405218); and White 2015, 94 – 95, no. 18.

Stefes 1997, vol. 2, 110 – 11, no. II/51.

Report by Annemarie Stefes from 2011, curatoral files, Ackland Art Museum. My thanks to Annemarie Stefes for further sharing her knowledge in subsequent verbal discussions.

British Museum, inv. no. 1920,214.2; and Stefes 1997, no. I/7.

For specific examples, see G. Wuestman in Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 120 – 22; A. K. Wheelock in Washington & Paris 2016 – 17, 59, no. 4; and Fucci 2018b (a review of the latter), 413, under no. 4.

My thanks to Annemarie Stefes for confirming this point.

The drawing does not appear in Stefes’s 1997 dissertation, but she confirmed the attribution to Berchem in 2011 (report in the curatorial files, Ackland Art Museum). While Begeyn’s modeling with washes is competent, it is frequently splotchier and less controlled; see, for example, his signed Goatherder and His Flock (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-t-1897-a-3334).

For the drawn copy, see Bock & Rosenberg 1930, vol. 1, 78, no. 330, vol. 2, pl. 64 (as Berchem); and Stefes 1997, no. AZ – 130, and under no. II/51, who identifies it as a copy and notes that the signature is not autograph. The copy is dated 1656. For the etching, see Hollstein, vol. 41, 64 – 66, no. 94 (part of a series of four prints depicting shepherds, nos. 91 – 94). One wonders if Jan de Visscher made the drawn copy himself, which is indeed indented for transfer, to aid in his making of the etching.

For Jan de Visscher’s prints after Berchem, see Wuestman 1996; and idem in Haarlem, Zürich & Schwerin 2006 – 07, 119 – 31. For Visscher generally, see Hawley 2014.