Choose a background colour

Cornelis Dusart, Dutch, 1660-1704

:

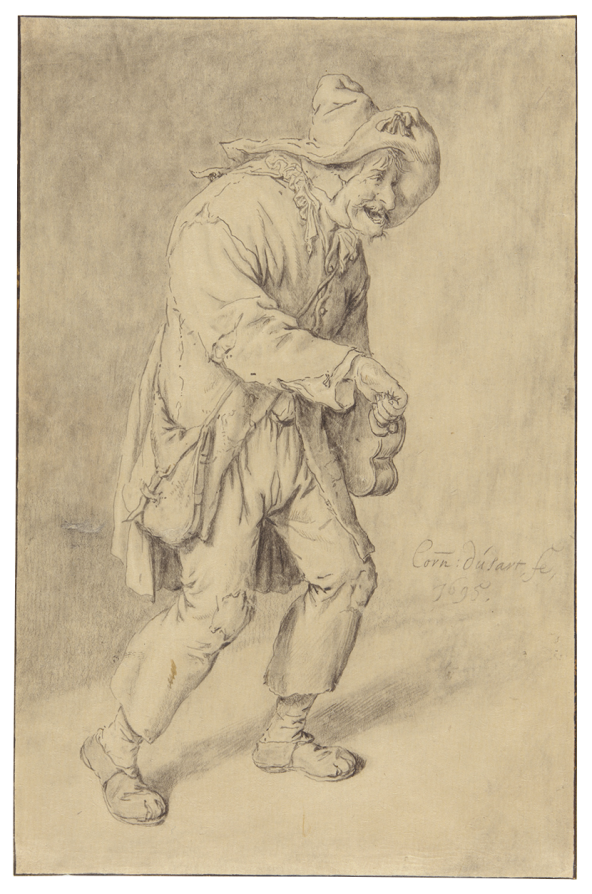

A Bagpiper, c. 1695

Pen and black ink with gray wash on Japanese paper.

7 1⁄16 × 6 1⁄8 in. (17.9 × 15.5 cm)

Recto, center left, signed and dated by the artist in pen, Corn: dusart fec’t / 1695; verso, upper left, in pencil, DD784- / RL 3 – 2.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

William Esdaile, 1758 – 1837, London (Lugt 2617, his inscription with date of acquisition and shelf mark on backing sheet, 1803 P39 N71); probably his sale, London, 18 – 25 June 1840, part 3, within the fifteen lots of Dusart drawings; private collection, Canada; sale, Christie’s, New York, 13 January 1987, lot 133 (together with related Fiddler by Dusart); Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.26.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

V. S. Lobis in Chicago 2019 – 20, 173 (note 27).

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.26

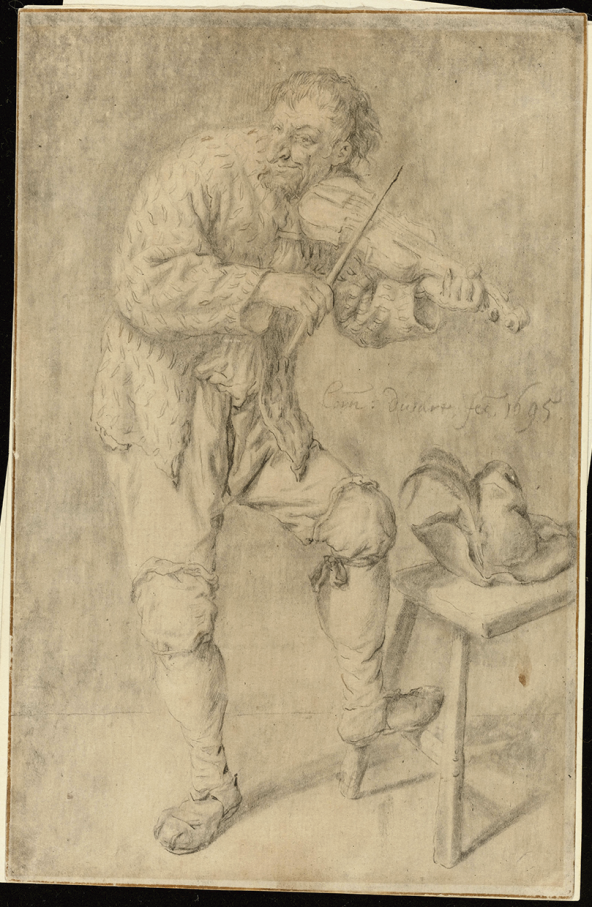

This depiction of a bagpipe player belongs to a series of four drawings featuring musicians, the others being fiddle, hurdy-gurdy, and lute players. Traditionally considered comic figures, bagpipe performers were often associated with festivities and dancing at village fairs, taverns, inns, and dancehalls, frequented particularly among the lower classes. In addition to his slouched posture and tattered appearance, contemporary viewers would have been amused by the extended position of his drone pipes, which should be resting on his shoulder.

Cornelis Dusart made this drawing on Japanese paper imported by the Dutch East India Company, a considerably more expensive material than European paper. The contrast between the low-life subject and its luxury support would have been highly appealing to collectors at the time.

Cornelis Dusart’s Bagpiper is one of a series of four signed and dated drawings of musicians that he executed on the costly and unusual support of Japanese paper.1

In contrast to the refinement of their execution, each shows a somewhat ragged and comically low-life figure playing an instrument.2

This Bagpiper can afford little facial expression since he is blowing intently on his mouthpiece, but the smiling countenances of the other figures in the series betray a festive demeanor, as one sees in the Fiddler Fig. 65.1, formerly in the Peck Collection but sold at auction in 2008, and the Hurdy-Gurdy Player in Chicago Fig. 65.2.3

Cornelis Dusart, The Fiddler, 1695. Pen and black ink with gray wash on Japanese paper, 179 × 115 mm. Present whereabouts unknown.

Sotheby’s

Cornelis Dusart, The Hurdy-Gurdy Player, 1695. Pen and black ink with gray wash on Japanese paper, 177 × 115 mm. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, inv. no. 1972.774.

Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Day Blake Memorial Fund

The fourth drawing, a Lute Player, was last recorded at auction in 1967 and has never been illustrated, but his likeness can be surmised from a mezzotint by Jacob Gole (1665– 1724) that faithfully reproduces the Hurdy-Gurdy Player alongside him Fig. 65.3.4

Jacob Gole, after Cornelis Dusart, The Hurdy-Gurdy Player and Lute Player, before 1724. Mezzotint and etching on paper, 175 × 204 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-p-ob-17.101.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

By Dusart’s day, artists had already developed a long tradition of comically depicting bagpipe players in prints from the German Renaissance onward.5

Iconographers have sometimes overstressed the erotic connotations of an instrument that resembles male genitalia, but a common thread that more safely unites these depictions is their nearly universal association with festivities, both urban and rural, and especially those that involve dancing. All four of the instruments in Dusart’s series are the type that might be performed at a kermis in a village, a rowdy tavern or inn, or in one of the musicos or dance halls that provided entertainment for the brothel-friendly habitués found in cities. The bagpipes and hurdy-gurdy, in particular, were associated with the lower classes, and thus instruments not to be handled by anyone with a sense of propriety.6

The violin and lute, however, were more “crossover” instruments in terms of class, and were sometimes found in the hands of artists themselves. For example, Dusart, who was the son of the organist of St. Bavo, owned two violins and likely knew how to play them.7

It is worth noting as well that the missing Lute Player bears a striking resemblance to the comic painter Jan Steen (1626 – 1679), who was fond of depicting himself playing that instrument.8

This is not to say that artists would hesitate to make specific associations with certain types of musicians. For an image of a bagpiper from 1630 by Jan van de Velde II (1593 – 1641), Samuel Ampzing (1590 – 1632) penned a verse that begins, “I belong to the sluggard’s guild, to the band of apprentice beggars who would rather play than work…” 9

This attitude finds correspondence in Dusart’s bagpiper, whose slouching pose and tilted head exhibit a certain insouciance, as does the fact that his drone pipes (the two sticking out furthest on the left) fall awkwardly in front of him rather than sit vertically against his shoulder, as was the norm. As Herman Roodenburg pointed out, it was precisely the perceived impropriety of these contorted poses that contemporary viewers found so comical.10

Scholars have speculated that this series of drawings and the related print by Gole were part of an effort to produce a series of musicians in mezzotint, as Dusart and Gole had done on other series.11

Only one pair of musicians appeared in print, however, suggesting that Gole did not actually collaborate with Dusart in executing the print of the Hurdy-Gurdy Player and Lute Player, but rather had access to Dusart’s drawings after the artist’s death. Gole made a similar mezzotint depicting two figures against a dark background generated from separate drawings by Adriaen van Ostade (1610 – 1685), almost certainly after that artist had died.12

He could have owned or had access to some of Ostade’s drawings (perhaps even from the estate of Dusart, Ostade’s pupil) from which he made prints on his own initiative. Furthermore, Dusart’s preparatory drawings for Gole’s mezzotints tend to be different in nature: looser and more wash-based in conjunction with the tonal values of that process. The signed and finished works discussed here, on the other hand, were clearly intended for the collectors’ market from the outset. By the eighteenth century, the two pairs of drawings of musicians by Dusart were already in separate collections: the Hurdy-Gurdy Player and Lute Player in the collection of Gerrit van Rossum (1699 – 1772), and the present work and the Fiddler in that of William Esdaile (1758 – 1837), each pair subsequently remaining together for two centuries.13

The Asian paper that Dusart used for this and the other drawings in the series, assumed with some confidence to be Japanese in origin, would have been a luxury support. The same can be said of vellum, which was also an expensive material that he and other artists would use for certain drawings, though paper like this from the other side of the world would have been less available. In Dusart’s day, it was called East-Indian paper (Oost-Indisch papier) since its only probable source would have been through trade with the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC). Rembrandt is credited for being the first Western artist to popularize the use of Asian paper, which he used for special impressions of his prints from around 1647 onward.14

Like vellum, it provides a slightly less absorbent surface, which accounts in some measure for Dusart’s delicately applied washes in this work, but also an appealingly buff tone that reduces overall contrast. Though he made these drawings decades after Rembrandt (1606 – 1669) experimented with Asian papers, Dusart’s series would have still been considered highly unusual — not to mention collectible— to its contemporary audience. In the same decade that Dusart drew these works, both Roger de Piles (1635 – 1709) and Florent le Comte (c. 1655 – c. 1712) wrote about the desirability of Rembrandt’s prints on Asian papers.15

William Esdaile, the earliest known owner of the present drawing, possessed a notable collection of such impressions of Rembrandt’s prints.16

He no doubt found the use of Asian paper for this drawing particularly appealing as well.

End Notes

The group of four drawings was first identified as a set by Susan Anderson, as cited by Victoria Sancho Lobis in Chicago 2019 – 20, 173, note 27. All four drawings are nearly identical in size, about 175/180 × 115 mm. An incorrect width of 155 mm for both the present drawing and the Fiddler is occasionally found in the literature, but this measurement repeats a mistake made in the 1987 auction catalogue in which both drawings appeared in the same lot (Christie’s, New York, 13 January 1987, lot 133).

The point about the contrast noted by Lobis in Chicago 2019 – 20, 146 – 47.

The Fiddler was sold at Sotheby’s, New York, 23 January 2008, lot 173. For the Hurdy-Gurdy Player in the Art Institute of Chicago (inv. no. 1972.774), see Chicago 2019 – 20, 294, no. 47; and Perlove & Keyes 2015, 144 – 45, no. 56.

For the drawing of the Lute Player, see sale, Venduehuis der Notarissen, The Hague, 7 – 8 November 1967, lot 138 (the Hurdy-Gurdy Player now in Chicago was lot 137). For the mezzotint by Gole, see Hollstein, vol. 7, 227, no. 189; and Wessely 1889, 62 – 63, no. 189.

See Antwerp 1994; and Winternitz 1979 (especially ch. 4, “Bagpipes and Hurdy-gurdies in Their Social Setting”). Bagpipers and other musicians were also a favorite subject of Dusart’s teacher, Adriaen van Ostade.

For the distinction, see the entries in Amsterdam 1997, nos. 18 (by Ger Luijten) and 38 (by Eddy de Jongh).

Anderson 2010, 137, 141 (note 20).

Jacob Gole also made a mezzotint that reproduces one of Steen’s self-representations playing the lute (presently in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional, Madrid); Hollstein, no. 121.

See Van Thiel 1996, 185. The original reads: “Ik ben van’t leuyaerds gild, en van de bedel-klerken / Die liever spelen gaen, dan dat sy souden werken.”

Roodenburg 1993. See further Knapp 1996, 37 – 39.

V. S. Lobis in Chicago 2019 – 20, 173 (note 27).

Hollstein, no. 200. Since a privilege appears on the print, and Gole received this right for the first time in 1688 (see Obreen 1877 – 90, vol. 7, 155), we can surmise that Gole published Ostade’s drawings posthumously. For Ostade’s original drawings of the figures that appear in the mezzotint, see Schnackenburg 1981, nos. 294 – 95.

For the pair of drawings in Van Rossum’s collection, see Dumas 2015, 255 – 56, nos. 199 – 200.

See R. Fucci in New York 2015, 19 – 20, with further references.

R. Fucci in New York 2015, 31 – 32.

See the entry for Esdaile (Lugt 2617) online: www.marquesdescollections.fr.