Choose a background colour

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669

:

Noli Me Tangere, c. 1655-56

Pen and brown ink with a few additions in wash and touches of white on paper; framing lines in brown ink.

8 9⁄16 × 7 5⁄16 in. (21.8 × 18.5 cm)

Verso, lower left, in pencil, J.5730 / 1120d.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 22 – 25 mm (24|25|22|25|24|25).

- Watermark:

- Foolscap with Seven Bells. Similar to Heawood, nos. 2000 and 2005; and Kettering 1988, nos. H214 and Gs20.

- Provenance:

Chevalier Ignace-Joseph de Claussin, 1766 – 1844, London and Paris (Lugt 485); Pierre Defer, 1798 – 1870, Paris (Lugt 739, mark on recto); by descent to his son-in-law, Henri Dumesnil, 1823 – 1898, Paris; sale of the Defer-Dumesnil collection, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 10 – 12 May 1900, lot 89 (from the “Collection du chevalier de Claussin”; 2300 fr. to Tuffi er); Théodore Tuffi er, 1857 – 1929, Paris; Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, 1863 – 1930, The Hague (Lugt 561); dealer, Paul Cassirer, Berlin and Amsterdam, probably mid-1930s; Franz W. Koenigs, 1881 – 1941, Cologne and Haarlem (Lugt 1023a); by descent to his daughter, Christine van der Waals-Koenigs, 1915 – 1995, Heemstede; sale of the Koenigs collection, Sotheby’s, New York, 23 January 2001, lot 17; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.68.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Lippmann & Hofstede de Groot 1903 – 11, vol. 4, no. 54; Paris 1908, no. 351; Bredt 1928, 110, 137; Valentiner 1934, vol. 2, 70, no. 511, 393; Haarlem 1951, no. 177; Rotermund 1952, 103, pl. 19b, and 120 (note 1); Benesch 1954 – 57, vol. 5, no. 993, fi g. 1206; Benesch 1960, no. 80, fi g. 80 (incorrectly as in the collection of Frits Lugt, The Hague); Haverkamp-Begemann 1961, 25 (pointing out that the drawing was not in the Lugt collection); Rotermund 1963, 265, 291, 315, no. 239; Slive 1965, vol. 2, no. 500; J. R. Judson in Chicago, Minneapolis & Detroit 1969 – 70, 56, under no. 43; Benesch 1973, no. 993, fi g. 1274; Bikker 2001, 75 – 79, under no. 5, fi g. 5d (attributed to Willem Drost); Peck 2003, 42 – 45, no. 10 (as Rembrandt); Bikker 2005, 61 – 65, under no. 5, fi g. 5d (attributed to Willem Drost); Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 5, 515 – 17, under no. V 18, fi g. 12 (as Rembrandt); G. Keyes in Paris, Philadelphia & Detroit 2011 – 12, 8 – 10, pl. 1.5, 27 (note 32), 247 – 48, no. 64 (as Rembrandt); Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 123, no. D153 (as Rembrandt); De Witt 2020, 214 (note 1), under no. D6.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.68

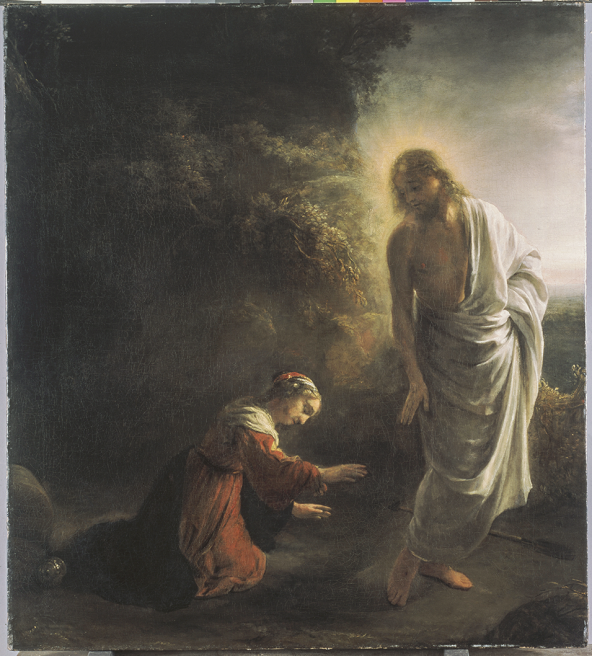

As related in John’s gospel (20:1-18), Mary Magdalene was the first to encounter Jesus after his resurrection, initially mistaking him for a gardener. It was only after he said her name that she knew his true identity. He instructed her, “Touch me not, for I am not yet ascended to my Father.”

Rembrandt depicts Mary kneeling in deference, face downward, with arms and fingers extended as Jesus blesses her. Astonished, she has knocked over her ointment jar, a detail that relates both Mary’s humanity in her blunder and Jesus’s divine nature, since the contents are no longer needed for his burial. With careful line work and a limited use of wash, Rembrandt creates an emotional and intimate moment, demonstrating his extraordinary ability as a storyteller.

Otto Benesch summed up the powerful nature of this drawing when he stated that it “combines monumentality of invention with utmost delicacy of presentation.“1

Rembrandt’s remarkable lightness of touch, enhanced here by a slight fading of the ink over time, intensifies the sense of the supernatural, especially the luminosity created by the aureole around the head of Christ. Such a treatment accords well with the biblical account of the Passion scene called Noli me tangere (Touch me not) from the Vulgate Latin version of the story told in John 20:1 – 18. Mary Magdalene was the first to encounter the resurrected Jesus after his Crucifixion. Having returned to his tomb, Mary wept at finding his body missing. When Jesus appeared behind her and asked about the nature of her distress, she at first mistook him for a gardener. It was only when he called her by name that his true identity became apparent. He then said to her: “Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father; but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and to my God, and your God.” (John 20:17). Rembrandt tended to use the motif of the aureole in this and other drawings during narrative moments when Christ’s divine aspect had just been revealed.2

In this case, Christ’s radiance even extends to the figure of Mary Magdalene, with one of the rays enveloping her figure, indicating spiritual “touch” despite the impermissibility of physical contact.

This drawing relates to Rembrandt’s horizontal-format painting of the subject from the early 1650s, a somewhat darkened and heavily restored canvas in Braunschweig Fig. 39.1.3

Rembrandt, The Risen Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene (“Noli me tangere”), c. 1650 or slightly later. Oil on canvas, 65 × 79 cm. Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, inv. no. 235.

bpk Bildagentur/Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum/Braunschweig/Germany/C. Cordes/Art Resource, NY

It shows the two figures on opposite sides of each other. Further differences include Christ’s flesh being further exposed in his shroud, and Mary Magdalene looking up instead of lowering her eyes. In the drawing, Mary has accidentally knocked over the jar of ointment (her attribute), a clever detail emphasizing the dramatic moment of surprise or revelation central to many of Rembrandt’s biblical subjects.4

One can also see her former companions walking into the distance at the right, missing in the painting. Rembrandt imbued the Christ figure in the painting, however, with a greater sense of contrapposto, having him lean more visibly away from Mary to emphasize the utterance of the words “touch me not” in that very moment. His left hand pulls the shroud closer to his body as he leans away. In the drawing, his right arm is not visibly depicted against the shroud, and his avoidance of her touch (or potential touch) is subtler. The reversal of the position of the figures may have to do with Rembrandt’s wish to show Christ blessing more properly with his right hand in the painting, thereby pulling away from Mary with his left hand against his body. If so, this would argue for the drawing having been made before the painting. Nevertheless, it does not appear to be a compositional study, but rather a drawing of a type that Rembrandt and his students would frequently make in order to explore the narrative potential of a scene, whether or not they had a planned painting in mind.5

Rembrandt had already painted the subject over a decade earlier in 1638, this time showing Christ as a gardener (as well as depicting the two angels sitting on the tomb who were also mentioned in the biblical text) Fig. 39.2.6

Rembrandt, Christ and St. Mary Magdalene at the Tomb, 1638. Oil on panel, 61 × 50 cm. London, Royal Collection, inv. no. RCIN 404816.

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Two related drawings by Rembrandt and Ferdinand Bol (1616 – 1680) also display compositional variations, but likewise probably date to around the same time as this earlier painting.7

Rembrandt’s depiction of Christ wearing a gardener’s hat and holding a shovel conforms more to the standard iconography of the era, and he would have been familiar with previous renditions of the subject, such as the prints by Albrecht Dürer and Lucas van Leyden that he very likely had on hand in his own collection.8

Whether Rembrandt had a particular visual source of inspiration for this later version showing Christ in his burial shroud, and without the appurtenances of a gardener, remains uncertain.9

A contemporary poem about the Braunschweig painting was written by his friend Jeremias de Decker (1609 – 1666) and published in the Hollantsche Parnas in 1660.10

De Decker devoted some of his verses to the emotions visible on Mary Magdalene’s face: “It seems as if Christ is saying: Mary, tremble not. / It is I. Death has no part of your Lord. / She, believing this, but not being wholly convinced, / appears to vacillate between joy and grief, between fear and hope.“11

One obvious difference between the painting and the drawing is that we do not have the benefit of seeing Mary’s face, bowed down instead in complete supplication. As George Keyes perceptively pointed out, a poignant aspect of this scene centers around the concept of verification by sight. Mary was specifically not allowed to touch Christ, unlike Thomas, who a short while later was permitted to put his finger in Christ’s wound to assuage his doubts.12

Conversely, Mary’s faith in Christ’s Resurrection could only be achieved through sight. Rembrandt was possibly playing on this exegetical aspect in the Peck drawing. Instead of registering surprise, desire, or distress, she lowers her eyes and spreads her hands in a graceful manner to signal her complete and serene acceptance.

In his monograph on the talented but short-lived Rembrandt pupil Willem Drost (1633 – 1659), Jonathan Bikker argued that the Peck drawing was actually a work by Drost, since it relates closely to a painting by him now in Kassel Fig. 39.3.13

Willem Drost, Noli me tangere, c. 1650 – 52. Oil on canvas, 95.4 × 85.4 cm. Kassel, Gemäldegalerie, inv. no. 261.

bpk Bildagentur/Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister/Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel/Art Resource, NY

There are certainly a number of points of similarity between the drawing and Drost’s painting, both in the overall composition and in certain details such as the knocked over jar of ointment and Mary’s lowered gaze, but these correspondences do not in themselves argue for Drost’s authorship. He almost certainly would have encountered this drawing in Rembrandt’s atelier during his years training there, around 1648 – 52, and the inspiration for his painting could have easily come directly from Rembrandt. Both Peter Schatborn and George Keyes rightly consider the Peck drawing a work by Rembrandt and reject the attribution of this drawing to Drost on stylistic grounds.14

Drost made his own drawing of the subject, now in Copenhagen Fig. 39.4.15

Willem Drost, Noli me tangere, c. 1650 – 52. Pen and brown ink with touches of white, 197 × 185 mm. Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, Den Kongelige Kobberstiksamling, inv. no. kks 7049.

National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen

It not only reveals his compact and stiffer style, but also that it more likely served as the compositional starting point for his related painting in Kassel.

End Notes

Benesch 1960, 158, no. 80.

Rotermund 1952, 102 – 04.

Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 5, 507 – 18, no. V 18; Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 6, 338 – 39, 610 – 11, no. 219; and Van de Wetering 2017, 338 – 39, 610 – 11, no. 219 (suggesting 1650 as the most likely date of execution). The painting is dated 165…, with the last digit illegible.

See Weststeijn 2008, 191 – 92, relating Rembrandt’s practice of showing sudden recognition to the ancient Greek literary concept of anagnorisis (discussed in Aristotle’s Poetics).

For the topic of Rembrandt and his students working out compositional ideas in their drawings, see H. Bevers in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 21 – 22. In the literature on Rembrandt’s painting, this drawing has also been deemed “related” rather than preparatory; see, for example, Corpus, vol. 5, 515.

Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 3, 258 – 64, no. A 124; Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 6, 252, 560 – 61, no. 158; and Van de Wetering 2017, 252, 560 – 61, no. 158.

Rembrandt, Christ Appears to Mary Magdalene as a Gardener, c. 1638 – 40 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP- T-1961-80); Schatborn 1985, 50 – 51, no. 22; and Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 77, no. D75. Ferdinand Bol, Christ Appears to Mary Magdalene as a Gardener, c. 1638 – 40 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-T-1930-29). For this pair of drawings, see also P. Schatborn in Los Angeles 2009 – 10, 98 – 101, nos. 12.1 – 12.2; and idem in Amsterdam 2017 – 18, 189.

Schatborn 1985, 50.

See the discussion in Corpus, vol. 5, 516. An Italian Renaissance precedent that comes somewhat close, showing Christ leaning away in his burial shroud (though still holding a gardener’s hoe) is the painting by Titian from circa 1514 in the National Gallery, London (inv. no. NG270).

De Raaf 1912; and Klessmann 1988. The poem was initially thought to refer to Rembrandt’s 1638 painting, but Klessmann (op. cit.) convincingly argued that it instead refers to the later painting in Braunschweig. For Rembrandt’s friendship with De Decker, whom he also painted, see Amsterdam 2019, 82 – 83.

Translation taken from Van de Wetering 2017, 610. For transcriptions of the complete poem, see De Raaf 1912, 6 – 7; and Corpus, vol. 5, 516.

G. Keyes in Paris, Philadelphia & Detroit 2011 – 12, 8 – 10. For further considerations of the Noli me tangere subject in Rembrandt’s oeuvre, see Perlove & Silver 2009, 308 – 11.

Sumowski Paintings, vol. 1, 613, no. 316; and Bikker 2005, 61 – 65, no. 5. See Bikker 2005, 64 – 65, for the attribution of the Peck drawing to Drost, where it is cited as a drawing formerly in the Lugt collection, repeating an error found in Benesch 1960, no. 80 (corrected in a review of the same, Haverkamp-Begemann 1961, 25). The connection between the Peck drawing and Drost’s painting was first noted by J. R. Judson in Chicago, Minneapolis & Detroit 1969 – 70, 56, under no. 43.

Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, no. D153; and G. Keyes in Paris, Philadelphia & Detroit 2011 – 12, 27 (note 32).

Sumowski Drawings, vol. 3, 1188 – 89, no. 547 x ; and Garff 1996, 38 – 39, no. 12. See also P. Schatborn in Los Angeles 2009– 10, 197 (and fig. 35a), citing this drawing as only one of two sheets that can be attributed to Drost with certainty; and D. de Witt in Amsterdam 2015, 76. See also another drawing given to Drost of the same subject in the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden (inv. no. C1369); Dittrich & Ketelsen 2004, 154 – 55, no. 79.