Choose a background colour

Frans van Mieris I, Dutch, 1635-1681: A Woman Asleep at a Table, c. 1660-70

Black chalk on vellum.

5 1⁄8 × 4 5⁄16 in. (13 × 11 cm)

Recto, lower left, in faded chalk, monogrammed FvM F (probably not by the artist); verso, lower left, in faded ink, h:5d, b:4 D (measurements in the hand of Ploos van Amstel); center left, in pencil, Fv.Mieris, lower left, fLu(?), at bottom center, 178, and lower right, 69.

- Chain Lines:

- None.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Aegidius Laurens Tolling, c. 1735 – 1786, Amsterdam; his sale, 21 November 1768, Album F, no. 352 (Een slapend Juffertje, met swart kryt getekend; fl . 6); sale, Amsterdam, 12 February 1770, no. 126; Jan Lucas van der Dussen, 1724 – 1773, Amsterdam; his sale, Amsterdam, 31 October 1774, Album H, no. 513; Cornelis Ploos van Amstel, 1726 – 1798, Amsterdam (Lugt 3004, his inscriptions, verso; see also Lugt 2034); his sale, Amsterdam, Ph. Van der Schley et al., 3 March 1800, Album C, no. 43 (Een slaapende Vrouw; fl . 9 to Van Loon); Max von Heyl zu Herrnsheim, 1844 – 1925, Darmstadt (Lugt 2879, stamp on verso); his sale, Stuttgart, H. G. Gutekunst, 25 May 1903, no. 191 (320 marks to Richard Gutekunst); John Postle Heseltine, 1843 – 1929, London (Lugt 1507, stamp on verso); Henry Oppenheimer, 1859 – 1932, London (Lugt 1351); his sale, London, Christie’s, 10 July 1936, no. 270B; sale, Paris, Tajan, 28 October 1994, lot 31; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.52.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

London 1910, no. 17; Naumann 1978, 31, no. 25, pl. 20a.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.52

Highly regarded in his lifetime, Frans van Mieris often depicted the lives of women in his paintings, including well-to-do mistresses, working-class maidservants, and brazen prostitutes. His genre scenes concerned themes of courtship, conviviality, love, but sometimes despondency. Here, a woman dozes at a table in a state of semi-undress, perhaps from overindulgence or idleness. Her identity remains tentative, but the curtained bed niche behind her indicates she might be a courtesan. Since the drawing is on vellum, or calfskin, rather than paper, it suggests Van Mieris either presented this sensitive portrayal as a gift, offered it to elite collectors, or placed it on the market as an affordable alternative to his paintings.

Frans van Mieris was a highly regarded artist in his lifetime and one who produced a prolific number of paintings.1

Surviving records and anecdotes suggest that he was also one of the best-paid painters of his day, with astounding sums offered by wealthy Dutch collectors and the upper ranks of European nobility for his works.2

His known drawings, on the other hand, are relatively few, numbering just over thirty today.3

The majority of them are delicately wrought, finished works in black chalk on vellum like this one, although a few sketches and compositional studies have also been identified.4

Together with a number of his contemporaries, including Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675), Van Mieris built on successful genre formulas that featured the lives of women as primary subject matter. This approach was developed by his teacher Gerrit Dou (1613 – 1675), who called Van Mieris “the prince of his pupils.” 5

Van Mieris treated a wide range of women, from fashionable mistresses to working maidservants to unrepentant prostitutes, often depicting them in situations revolving around love, courtship, merriment, or despair. Sometimes they appear alone, as here, but more frequently in the company of auxiliary characters, such as male suitors.

Surviving drawings by this group of artists are especially rare (no secure drawings, for example, are known by Dou or Vermeer), making Van Mieris’s relatively small corpus of drawings all the more significant. He may have gifted or sold many of the finished sheets to the same elite collectors who could afford his paintings, or perhaps he offered them as less expensive alternatives to his paintings.6

His evident command of the medium is not surprising given Houbraken’s tale of Van Mieris as a boy drawing on the walls of his father’s workshop with charcoal, an act that led his father to place him with his first teacher, the Leiden drawing master Abraham Toorenvliet (1600/17 – 1692).7

Van Mieris displays remarkable control of the black chalk in this work, varying the thickness of the point to achieve notably distinct textures. One sees this in the finely modeled areas of flesh in the woman’s hand, face, and exposed breast, contrasted with the looser and more vigorous modeling of her chemise.

Although the exact cause of the woman’s sleep is unclear, the motif of a drunken woman asleep at a table became a popular one among Van Mieris, Dou, and Jan Steen (1626 – 1679) in the early 1660s.8

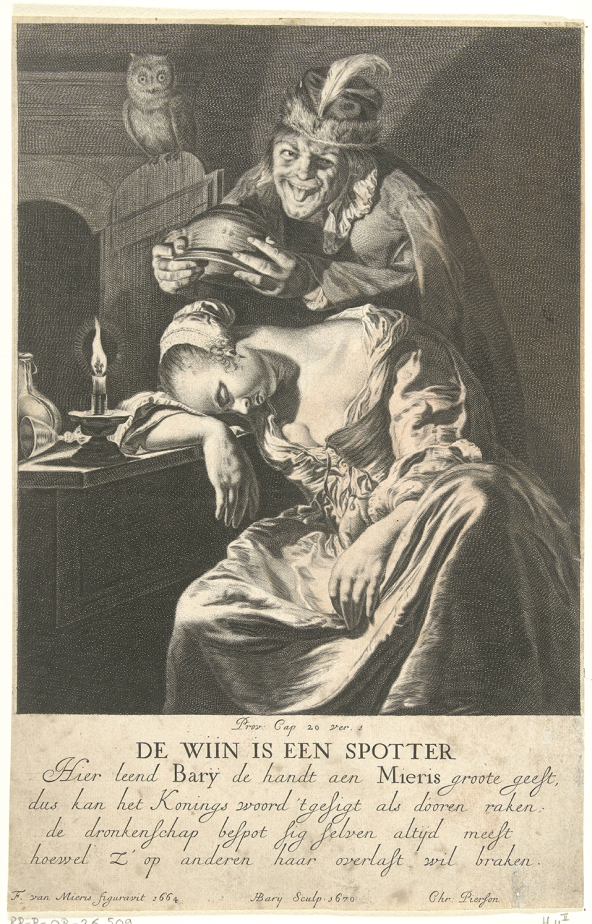

Their paintings drew on a tradition that had put men (often soldiers) in this role being mocked, robbed, or even tickled, but gave the subject a twist of gender for comic effect. They invariably depicted such drunken women with a certain amount of disheveled undress or exposed décolleté. Van Mieris made the association with drunkenness explicit in another drawing dated 1664, the original of which is now lost but known in copies, and from a print by Hendrick Bary from 1670 titled De wijn is een spotter (Wine Is a Mocker) Fig. 53.1.9

Hendrik Bary, after Frans van Mieris, De wijn is een spotter (Wine Is a Mocker), 1670. Engraving on paper, 285 × 185 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-p-ob-26.509.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The source of the sleeping woman’s inebriation in Bary’s print is made clear by the wine bottle and overturned goblet by her hand, while a fool-like figure symbolically (rather than literally) dumps a chamber pot over her head. The latter trope was a standard gag in comic theater at the time.10

It has previously been suggested that the Peck drawing may have been an initial conception for “Wine Is a Mocker.“11

This supposition is tempered, however, by the fact that the woman is not slumped over in a full stupor but rather seems to be pleasantly dozing. It also lacks any trace of drink, glass, or bottle that one typically finds in such works, as well as any additional figures to cue the viewer toward amusement or moralizing sentiment. Another possibility is that Van Mieris intended an allusion to the sin of sloth. Sleeping figures, both male and female, had long been used to represent laziness and idleness.12

At the same time, no iconography of neglect is visible, such as one finds in paintings by Nicolaes Maes (1634 – 1693) from the 1650s showing sleeping maidservants who idle amid the objects of their chores.13

Despite being described as a “lady” (dame) in an eighteenth-century auction catalogue, Van Mieris’s clearly erotic presentation signifies by default a class somewhat below that of the haute bourgeoisie.14

It is not impossible that she represents a prostitute. Van Mieris made the sleeping woman as courtesan concept unambiguously clear in a painting in the Uffizi, in which the woman’s décolleté is taken to the extreme, while a man in the background pays the old procuress for services rendered.15

Curtained bed niches, such as the one in the background of this drawing, often signaled that we might in fact be in the presence of a comely courtesan in her chamber.

Regardless of her profession or state of sobriety, this drawing appears to be the only known instance of Van Mieris specifically portraying a woman sleeping on her propped arm. Worth considering is that Van Mieris knew the painting by Vermeer, A Maid Asleep, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, generally dated circa 1656 – 57 53.2.16

Johannes Vermeer, A Maid Asleep, c. 1656 – 57. Oil on canvas, 87.6 × 76.5 cm. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 14.40.611.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913

It was described in a 1696 auction catalogue as “A drunk sleeping maid at a table” (Een dronke slapende Meyd aen een tafel).17

Since Van Mieris and Vermeer worked in the relatively nearby towns of Leiden and Delft, there is no reason to doubt that they took an interest in each other’s paintings, as Adriaan Waiboer has argued.18

One recently discovered drawing by Van Mieris establishes that he even might have sketched a quick aide-mémoire after seeing a painting by another artist.19

If there is a connection between the present Van Mieris’s drawing and Vermeer’s painting, it would be impossible to say for sure who influenced whom, but this drawing most likely dates a few years later than Vermeer’s painting

End Notes

See Naumann 1981 for the catalogue of paintings; updated in The Hague & Washington 2005 – 06, 232 – 39. For Van Mieris’s reputation, see Buvelot in The Hague and Washington 2005, 12 – 26.

For the prices of Van Mieris’s paintings and those of his contemporaries, see Paris, Dublin & Washington 2017 – 18, 268 – 69.

The basic catalogue of drawings is Naumann 1978; updated in The Hague & Washington 2005, 239 – 41.

For his sketches and studies in general, see Pottasch 2005, 65 – 67; and I. van Tuinen in Washington & Paris 2016 – 17, 251 – 53, no. 114. For descriptions of some notable examples of his finished drawings on vellum, see, among others, New York & Paris 1977 – 78, 101 – 02, no. 69; Broos & Schapelhouman 1993, 115 – 19, nos. 84 – 85; London, Paris & Cambridge 2002 – 03, 210 – 11, no. 92; and New York 2012, 170 – 71, no. 72.

The interactions among these artists are the subject of Paris, Dublin & Washington 2016 – 17.

In at least one instance, we know that a highly finished drawing on vellum was for one of Van Mieris’s major patrons, the Paets family; for which see Van Gelder 1975; Naumann 1978, no. 12; and The Hague & Washington 2005, no. 36. For Van Mieris’s major patrons, see Bakker 2017a. For the suggestion that his finished drawings could serve as less expensive alternatives to paintings, see W. W. Robinson in London, Paris & Cambridge 2002 – 03, no. 92.

Houbraken 1718 – 21, vol. 3, 2.

E. Schavemaker in Paris, Dublin & Washington 2017 – 18, 179 – 83; For sleeping figures generally in seventeenth-century Dutch art, see Salomon 1984.

For the lost original and a drawn copy, see O. Naumann in Washington, Denver & Forth Worth 1977, 82 – 84, no. 79; and Naumann 1978, no. 24. For the numerous painted copies of the drawing, see Naumann 1981, vol. 2, 155 – 56, no. C62. For what might be a counterproof of the lost drawing, see Vevey 1997 – 98, 120 – 21, no. 66. One of the main reasons to posit that the original was a drawing instead of a painting is that Bary’s print specifically says F. van Mieris figuravit instead of pinxit

E. de Jongh in Amsterdam 1997, 337 – 40, no. 71; see also Amsterdam 1976, 246 – 49, no. 65.

Naumann 1978, 31, no. 25.

For a full-length study of the sleeping figure iconography, see Salomon 1984.

See, for example, Nicolaes Maes, The Idle Servant, 1655, oil on panel; The Hague & London 2019 – 20, nos. 84 – 87, no. 9. For Maes’s other sleeping figures of men and older women, see idem, nos. 10, 11, 13.

“Een bevallige Dame, zittende te slapen…” (An attractive Lady, sitting asleep…). See the provenance notes in the present entry for the Van der Dussen sale, 1774.

Sleeping Courtesan, 1669, oil on copper, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. See Naumann 1981, vol. 2, 89 – 91, no. 75; and Naumann 2005, 39 – 40.

While the literature on Vermeer’s Maid Asleep is substantial, see especially Kahr 1972; New York & London 2001, 369 – 71, no. 67; and Liedtke 2007, vol. 2, 868 – 77, no. 202.

Montias 1989, 364, no. 8, in doc. 439.

Waiboer in Paris, Dublin & Washington 2017, 18 – 19 (and fig. 9), citing an unpublished essay by Otto Naumann.