Choose a background colour

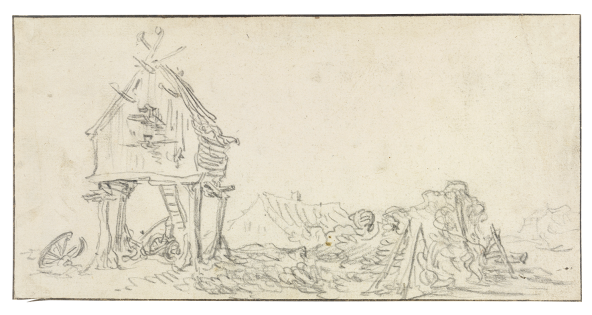

Jan van Goyen, Dutch, 1596-1656: Figures in a Boat near a Dovecote, c. 1640-50

Black chalk and gray wash on paper; framing lines in black chalk, strengthened in some areas with black ink.

4 5⁄16 × 7 1⁄2 in. (10.9 × 19.1 cm)

Recto, lower right, pen and ink, 302 (Flury-Hérard collector’s mark number).

- Chain Lines:

- Horizontal, 23 – 25 mm.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Prosper Flury-Hérard, 1804 – 1873, Paris (Lugt 1015, stamp on recto, with inventory number 302 in pen and ink); his sale, Delbergue, Paris, 13 May 1861, lot 145 (ff 6.50 to Charles Blanc); Charles Blanc, 1813 – 1882, Paris; Mrs. A. L. Snapper; her sale, Sotheby’s, London, 10 May 1961, lot 79 (£140 to Houthakker); dealer, Bernard Houthakker, Amsterdam (cat. 1961, no. 28); sale, The Hague, 7 June 1966, lot 292; sale, Sotheby Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 18 November 1980, lot 112; sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 16 January 1985, lot 69; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.38.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Beck 1972 – 91, vol. 1 (1972), 316, no. 848e (as copy after lost original, later accepted as authentic), vol. 3 (1987), 109, no. 694a (as authentic); F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 56 – 58, no. 12.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.38

Jan van Goyen’s simple, yet direct approach to the Dutch countryside, with its emphasis on tonality and naturalism, had a lasting impact on his contemporaries. He made over 1,000 drawings, both sketches and finished works, the latter destined for the market.

This finished drawing depicts a wooden dovecote, a shelter for domesticated pigeons raised on poles or tree trunks. Because pigeons were a source of food and a commodity, dovecotes were highly regulated and permitted among the upper echelons only, that is, until laws were relaxed in the later seventeenth century. If the dovecote in Van Goyen’s drawing is illicit, the image would have provided a source of amusement for his viewers, many of whom appreciated representations of such rural daily life in landscape art.

Jan van Goyen was a prolific and highly regarded painter in his day whose experiments with new styles of landscape painting had a lasting impact on many of his contemporaries, in particular his “tonal” or nearly monochrome paintings.1

He was a truly prolific draftsman as well. His body of over 1,000 drawings is one of the largest to survive today by a seventeenth-century Dutch artist.2

The majority of these were finished drawings for the market, though many of his sketches and even a few of his sketchbooks also survive, providing insight into his travels and working methods.3

Van Goyen would regularly work up motifs from his sketches into both finished paintings and finished drawings, sometimes years after he first sketched the motifs from life.4

Despite the lack of a monogram and date, both of which he often (though not always) added to his drawings, Van Goyen almost certainly intended this sheet as an autonomous finished work. It is the type of work he would have made in the studio, perhaps with the aid of studies taken from life, such as his sketch of a dovecote now in Braunschweig Fig. 36.1, or something similar but no longer extant.5

Jan van Goyen, Sketch of a Dovecote, 1636. Black chalk, 118 × 237 mm. Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, inv. no. z.1266.

1 bpk Bildagentur/Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum/Braunschweig/Germany/Art Resource, NY

For his final composition, Van Goyen used swift and controlled strokes with a relatively blunt nib of chalk, conveying an energetic avian-like vibrancy to the image as a whole. This confident and distinctive handling of the chalk suggests a date for this work in the early 1650s.6

This was an immensely productive period for the artist in terms of his drawings, with over 350 of his signed and dated sheets coming from the years 1651 – 53 alone.

Images of dovecotes prove interesting given that regulations around their ownership changed over the course of the seventeenth century, at least in the Netherlands.7

In previous centuries across Europe, only nobles and high clergy were permitted the right to build dovecotes, a law that was upheld in Utrecht as late as 1647, with increased fines for those found illegally keeping them.8

Obviously, as a food source and marketable item, domesticated pigeons would have been a desirable commodity.9

Regulations were loosened in the latter half of the seventeenth century to allow farmers with a certain amount of acreage to keep them.10

Authorities probably did not strictly enforce these measures in the first place. As one historian already noted, their regular appearance in the visual arts from the beginning of the seventeenth century onward seems to belie their unauthorized status, though perhaps that was part of the point of these representations.11

Van Goyen himself depicted dovecotes throughout his career. Artists from the previous generation, such as Abraham Bloemaert (1566 – 1651), made use of the motif on several occasions, as did Jan van de Velde II (1593 – 1641), whose etching of a dovecote bears a compositional similarity to the Peck drawing Fig. 36.2.12

Jan van de Velde II, Landscape with Dovecote, 1616. Etching, 132 × 205 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-p-1898-a-20422.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Van Goyen’s teacher, Esaias van de Velde (1587 – 1630), was also fond of the dovecote motif.13

These wooden types raised on poles or tree trunks (duiventillen) usually belonged to farmers or villagers, as opposed to the brick structures (duiventoren) found on estates or attached to the sides of châteaux.14

Dovecotes have occasionally provoked discussions in the scholarly literature over their iconographic associations and the degree of interpretive weight that should be accorded to them.15

In the present sheet, the figure boarding the boat bears a wicker poultry basket in his right hand, suggesting Van Goyen simply intended to depict a farmer heading to market with livestock from the dovecote. The large object being rolled by his left hand might be a similar lightweight container of some sort (rather than a barrel, which it resembles at first glance). If this was an illicit dovecote, such common knowledge would have provided a humorous layer of meaning for Van Goyen’s contemporary audience, for whom depictions of the various activities of rural folk were welcome and animating features in landscape art.

This drawing has the distinction of having belonged to one of Van Goyen’s fiercest defenders in the nineteenth century, the French art critic Charles Blanc (1813 – 1882). After a decline in appreciation in the eighteenth century, Van Goyen’s works gained renewed attention among connoisseurs in the era of Impressionism, although the sheer prolificacy of his works tended to keep their market value low, and by extension their appeal among certain snobbish collectors. Blanc vented: “These moderate prices are undoubtedly the reason why we do not see anything of Van Goyen in the most celebrated galleries… Gallery owners should be a little less vain and have a bit more insight, more [concern with] true art.” 16

That he wrote this around the same time that he came into possession of the present sheet is a compelling aspect of its provenance. Blanc purchased it at auction in 1861 for the relatively low sum of six francs from the collection of Flury-Hérard, whose prominent stamp can be seen in the lower right corner (F.H. No., followed by 302 in ink).

End Notes

For an overview of Van Goyen’s life, his landscape style, and its impact, see especially Leiden 1996.

For the standard catalogue of Van Goyen’s drawings, see the first volume (1972) and third volume (1987 supplement) of Beck 1972 – 91.

For Van Goyen’s sketchbooks, see Beck 1972 – 91, vol. 1, 254 – 315, nos. 843 – 47; Buijsen 1993; and E. Buijsen in Leiden 1996, 22 – 37.

For an overview of Van Goyen’s uses of drawings as preparatory material, see I. van Tuinen in Washington & Paris 2016– 17, 127 – 31, nos. 42 – 44. See especially idem, 129 (and note 13), which corrects Beck’s assumption that some of Van Goyen’s finished drawings served as an intermediate stage of preparation for his paintings, rather than being separately worked up from sketches (for which see Beck 1957).

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, inv. no. Z.1266; see Beck 1972 – 91, vol. 1, no. 738A; and idem, vol. 3, no. 738A (where illustrated).

This opinion differs from that of Franklin Robinson, who dated the drawing to the 1640s in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 56 – 58, no. 12. Van Goyen’s handling of certain passages such as the foliage tends to be looser in the 1650s, whereas his drawings from the 1640s (considerably fewer in number) betray a tighter, more concerned approach like that of Pieter Molijn.

Giezen-Nieuwenhuys & Wilmer 1987, 35 – 40; and Wttewaall 1991.

Wttewaall 1991, 7.

For the various uses of doves and pigeons in the seventeenth century, with a focus on Spain, see Canova 2005.

For the change in Utrecht’s regulations in 1667, see Wttewaall 1991, 7. For the suggestion that other regions loosened regulations after the Treaty of Münster (1648), see Giezen-Nieuwenhuys 1987, 35.

Van Ballegooyen 1978, 123.

For some of Bloemaert’s paintings and drawings with dovecotes, see Utrecht & Schwerin 2011 – 12, nos. 64, 68 – 70. For Van de Velde’s etching, see Hollstein (vols. 33 – 34), no. 246.

See Keyes 1984, passim.

For dovecote architecture in the Netherlands, see Van Ballegooyen 1978; Giezen-Nieuwenhuys & Wilmer 1987; and Wilmer 1991.

Leeflang 1995, 278 and note 19; and Gibson 2000, 163 and note 85 (page 231).

Blanc 1861, 8; cited by W. L. van de Watering in Amsterdam 1981, 33 – 34 (from the 1876 edition); and in Buijsen 1993, 20, from which the English translation is taken.