Choose a background colour

Abraham Bloemaert (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht)

:

Studies of Hands and Legs from a Sketchbook (Recto: Studies of Hands; Verso: Studies of Hands and Legs), c. 1595 – 1605

Red and black chalk with white highlights on paper; framing lines on recto in brown ink; framing lines on verso, lower right corner only, in brown ink.

10 3⁄16 × 6 1⁄8 in. (25.8 × 15.5 cm)

Recto, upper right corner in pen and ink, 11; verso, upper right corner in pen and ink, 10.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 25 – 27 mm

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

André Giroux, 1801 – 1879, Paris (Lugt 5838); his sale, Delteil, Paris, 18 – 19 April 1904, part of lot 175 (Etudes de personnages, de paysages et d’animaux. Cent trente-six dessins, la plupart executes à la sanguine, un certain nombre avec d’autres croquis au verso); dealer, W.R. Jeudwine, London; dealer, Faerber and Maison, London, 1967; David Daniels, New York; his sale, Sotheby’s, London, 25 April 1978, lot 47; sale, Sotheby’s, Amsterdam, 13 November 1991, lot 291; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.6.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

London 1966, 32, no. 34; Minneapolis, Chicago, Kansas City & Cambridge 1968, no. 4; Poughkeepsie 1970, 28, no. 21; New York 1973, no. 11; Boon 1992, vol. 1, 28 – 29, under no. 12 (note 2); Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 400, under no. T53; Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 351, nos. 1095 – 1096, vol. 2, 381, pls. 1095 – 1096; Bolten 2017a, 114, nos. 10 – 11.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.6

A leading artist and famous teacher of drawing, Abraham Bloemaert co-established a drawing academy in Utrecht around 1612 where students learned to sketch from live models. Bloemaert trained over 100 artists over the course of his career, and with his publications, he influenced generations of artists. This double-sided sheet of hands and legs belonged to a larger group of drawings featuring carefully arranged motifs that were later engraved. Meant for Bloemaert’s Tekenboek (Drawing Book), the designs served as source material for artists as well as amateurs.

Four of the motifs on this sheet were included in the Tekenboek—one of the hands holding a staff; the hand holding a cloth; the hand with the outstretched fingers; and the folded hands on the reverse.

Abraham Bloemaert had one of the longest careers of any Dutch painter in his era and was famed as a teacher of drawing. Along with Paulus Moreelse (1571 – 1638), he established a drawing academy in Utrecht around 1612, one of the first of its kind, in which groups of students could learn to draw from live models under the masters’ watchful eyes. It is estimated that Bloemaert had over 100 students, including his four sons who all continued in the profession.1 Unsurprisingly, given the length of his career, his commitment to drawing, and the didactic side of his profession, Bloemaert left behind an unusually large body of drawings, today numbering over 1700 documented works.2

This double-sided sheet comes from the so-called Giroux Album, a loose group of 136 drawings of various sizes and subjects that once belonged to the French landscape painter André Giroux (1801 – 1879).3 The majority of the sheets, like this one, consisted of agglomerates of studies of hands, limbs, figures, or animals, extracts of which were later engraved by Abraham’s son, Frederick (1614/17 – 1690). The prints appeared as part of Bloemaert’s famous Tekenboek (‘Drawing Book’), a large collection of such motifs intended for artists and amateurs which remained popular well into the eighteenth century.4 It was not a manual or treatise, per se, since no text accompanied the plates, but rather a visual compendium of Bloemaert’s studies. The individual motifs on each sheet found throughout the now-dispersed Giroux album were rearranged before publication, and not all of them were used.5 Frederick must have worked closely with his father around 1648 – 50 (when Abraham was in his early 80s) to finally realize the publication, which seems to have been issued initially in loose sets of prints around 1650 before later appearing in bound form. Four of the various motifs found on the present sheet ultimately found their way into the publication, in reversed form on the engraved plates: one of the hands holding a staff at the top of the recto; the hand below them squeezing a cloth; the hand with outstretched fingers in the lower right; and, on the verso, the pair of folded hands at the bottom of the sheet Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3.6

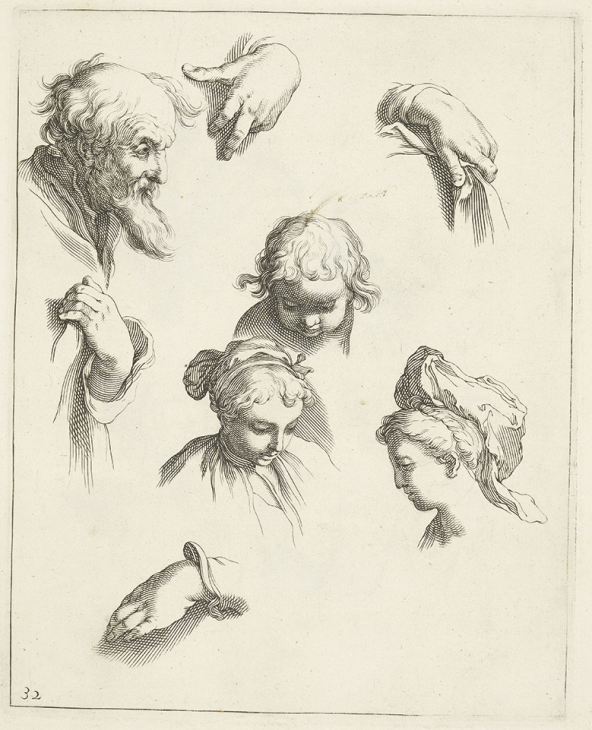

Frederick Bloemaert, Hands (plate 53 of the Tekenboek, 1740 edition), c. 1650. Engraving, 215 × 173 mm. London, British Museum, inv. no. l,83.1.

The Trustees of the British Museum

Charting the journey of these studies from their creation to their ultimate appearance in print remains a somewhat conjectural exercise, beginning with the difficulty of dating drawings like this one.7 Marcel Roethlisberger suggested a two-decade range in the 1620s and 1630s for most of the Giroux album’s contents.8 For the Peck drawing, however, Jaap Bolten posited a much earlier creation in the years c. 1595 – 1605, which would make it one of the earliest of Bloemaert’s study sheets to survive.9 His assessment was due to the sheet’s clear (and appealing) Mannerist style, with the elegantly elongated fingers and tensely spread hands that one finds throughout Bloemaert’s early oeuvre. Furthermore, one of the outstretched hands (in the lower right on the verso) recurs in that of a shepherd in a painting of the Adoration of the Shepherds by Bloemaert datable to c. 1602 – 09.10

Frederick Bloemaert, Heads and Hands (plate 19 of the Tekenboek, 1740 edition), c. 1650. Engraving, 215 × 172 mm. London, British Museum, inv. no. l,83.33.

The Trustees of the British Museum

There is no reason to suppose that the drawings in the Giroux Album were necessarily all made around the same time. These drawings collectively seemed to have served as an atelier thesaurus, a slowly built-up collection of motifs made for repeated, long-term use by artists and assistants in the studio that aided in the invention or execution of compositions.11 What is striking about this and other such drawings by Bloemaert is their carefully finished nature, with the motifs attractively worked up with white highlights, and a mise-en-page that suggests a diligently planned arrangement. The term sketchbook as applied here may indeed be a misnomer, especially since motifs like these were not necessarily drawn from life. Stijn Alsteens pointed out that such attractively finished sketches would have appealed to early collectors (as they do to us today) purely for the beauty of their draftsmanship.12 Most of these drawings nevertheless appear to have remained in the studio, at least until the end of Abraham’s career and the preparation of his Tekenboek.

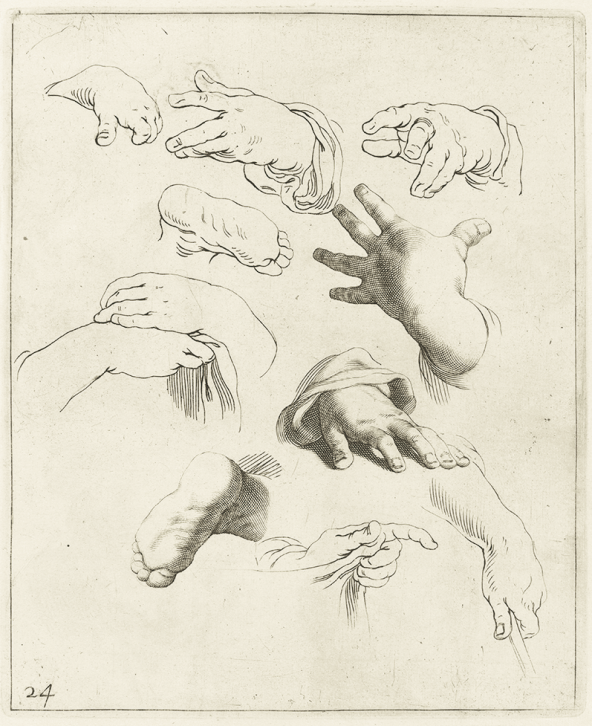

Frederick Bloemaert, Hands and Feet (plate 55 of the Tekenboek, 1740 edition), c. 1650. Engraving, 210 × 170 mm. London, British Museum, inv. no. l,83.25.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

It has long been hypothesized that the original sequence of drawings in the Giroux Album reflects an earlier but failed attempt to publish the contents of Bloemaert’s atelier thesaurus in printed form.13 If so, what foiled this first attempt remains unknown, but the numbering of these sheets in their upper-righthand corners by an apparently early hand (10 and 11 in this case) might just as easily reflect a posthumous ordering by a family member or early collector, rather than an initial cull for potential publication. The reason for their complete rearrangement in preparation for their appearance in the Tekenboek around 1650 appears to have been a desire to impose a better sense of order by grouping the motifs more thematically.14 It is notable that the Mannerist style of this sheet was clearly curbed for the final publication, in which the fingers do not stretch quite so tautly or languorously. Such a style would have seemed retardataire by the mid-seventeenth century, however attractive it remains for us today.

End Notes

For an overview of Bloemaert’s life and art, see especially Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 15 – 40, and 551 – 587; and for his drawing academy and pupils specifically, idem, 571 – 575.

Catalogued in Bolten 2007; with supplement, Bolten 2017a.

For the Giroux Album, see Bolten 1993, 3 – 4; Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 392; Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 361 – 362; and Bolten 2017a, 114 – 115.

Bolten 1985, 253 – 256; Bolten 1993, Roethlisberger & Bok, 1993, vol. 1, 389 – 394; Nogrady 2009, 226 – 231; and Bolten 2017b. Early editions of the Tekenboek are extremely rare, with only a few examples from the 17th century still extant, probably more due to use than lack of popularity. It is best known and studied today through the 1740 Ottens edition (see Bloemaert 1740).

The final arrangement can be found in the set of drawings that comprise the still-intact Cambridge Album; see Bolten 1993; Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 390 – 391; and Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 362, and catalogue nos. 1137 – 1313. The authorship of the Cambridge Album drawings has been variously assigned to either Frederick or Abraham himself.

These appeared as plates 7, 32, and 24 in early editions; and in the 1740 Ottens edition as plates 53, 19, and 55. For the related drawings in the Cambridge Album, see Bolten 2007, nos. 1156, 1181, and 1173. For the prints, see Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, nos. T53, T19, and T55.

Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 5 – 6.

See the discussion in Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, vol. 1, 389 – 392.

Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 351, nos. 1095 – 1096.

Berlin, Staatliche Museen, inv. no. 745; Roethlisberger & Bok 1993, no. 66; Utrecht & Schwerin 2011 – 12, no. 21. This drawing’s correspondence with the painting was first spotted by Bolten (see Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 351, no. 1095) though repeating the date of the painting found in earlier literature as 1604. Roethlisberger pointed out that the last digit is illegible, but says that it could only be a 2, 3, 5, 8, or 9. The date of the painting does not necessarily provide a reliable terminus ante quem for the drawing, but a date in the same period does seem a reasonable supposition.

Bolten 2007, vol. 1, 361.

S. Alsteens in New York 2009, 97, no. 45. For an opposing view, see A. Elen in Utrecht & Schwerin 2011 – 12, 38 (note 4).

See the references on the Giroux Album as in note 3, above. Bolten recently reaffirmed this hypothesis in Bolten 2017b, 114 – 115, citing his forthcoming introduction to a facsimile edition of Bloemaert’s Tekenboek.

See the references for the Cambridge Album in note 5 above.