Choose a background colour

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669: Seated Man Warming His Hands by a Fire, c. 1650

Pen and brown ink with corrections in white on paper; framing lines at top, left, and bottom in brown ink, and at right in black ink.

5 15⁄16 × 6 7⁄8 in. (15.1 × 17.5 cm)

Recto, lower right, in pencil (faintly) R.V.R….n.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 21 – 25 mm (21|22|22|24|25|23|25)

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Nathaniel Hone, 1718 – 1784, London (Lugt 2793, his stamp, an eye, lower right); his sale, Hutchins, London, 7 – 14 February 1785; dealer, P. & D. Colnaghi, London, 1958; sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 26 January 2000, lot 27; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Musuem, inv. no. 2017.1.66.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Benesch 1960, 154, no. 58, fi g. 58; Benesch 1973, vol. 5, 309, no. 1153A, fi g. 1450; Peck 2003, 32 – 33, no. 7; Sciolla 2007, 173 – 74, under no. 135, fi g. 135a; Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, 262, no. D421a.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.66

This drawing of a seated old man warming his hands by the fire might depict the biblical patriarch Tobit, whom Rembrandt represented in this manner on numerous occasions. Bundled in a long coat, house slippers, and a hat with ear flaps, the introspective figure reflects Rembrandt’s interest in expressing the complex inner lives of solitary figures during the early 1650s. Dissatisfied with his first rendition of the hands low against the man’s lap, Rembrandt moved them higher, applying white chalk or gypsum as a corrective medium that has since faded away. His frequent use of this method to edit his drawings reveals both the artist’s creative process and experimental working method.

This drawing came to light shortly after Otto Benesch published the first edition of his comprehensive catalogue of Rembrandt drawings in 1954 – 57, but its appearance was not a complete surprise since the image was previously known through a copy in the Biblioteca Reale in Turin Fig. 38.1.1

Follower of Rembrandt, Old Man Warming His Hands by a Fire. Pen and ink on paper, 147 × 207 mm. Turin, Biblioteca Reale, inv. no. 16445b D.C.

With permission © MiC - Musei Reali, Biblioteca Reale di Torino

Benesch ascertained that the Turin drawing must have been a copy before he knew of the original’s existence given the copy’s incoherent forms and hesitation of line in certain areas. The date of the original, the present sheet, can be placed on stylistic grounds in the early 1650s.2

Rembrandt frequently made changes to his sketches, especially to try out different positions of limbs, either to give them greater expressive meaning or to clarify the composition.3

In this case, he raised both the man’s hands and opened his palms slightly in order to create a more convincing sense of receiving warmth from the open fire of the hearth. Rembrandt covered the corrected passage with a white body color, as was often his habit. While it has frequently been assumed that this is a lead-white, it could also (and perhaps more likely) be a white chalk or gypsum.4

The corrections in white have mostly worn away, leaving the original passage largely exposed and affording us an even better glimpse at Rembrandt’s working process. He probably drew the seated figure first, and only after sketching in the hearth and mantle realized a need to adjust the figure’s hands to better conform to the position of the fire.

As Benesch already noted, the figure is reminiscent of one of Rembrandt’s many representations of the biblical Tobit.5

There is nothing in the iconography here to make such a connection strictly clear, but the placement of the seated old man by a fire is suggestive of the story. Episodes from the Book of Tobit were highly popular with Dutch artists at the time, and especially with Rembrandt and his pupils. This text was canonical to Catholics, but despite its status as Apocrypha to the Protestants, it was still widely studied in the Netherlands, and appeared in the Dutch-language Bible approved by the Synod of Dordrecht.6

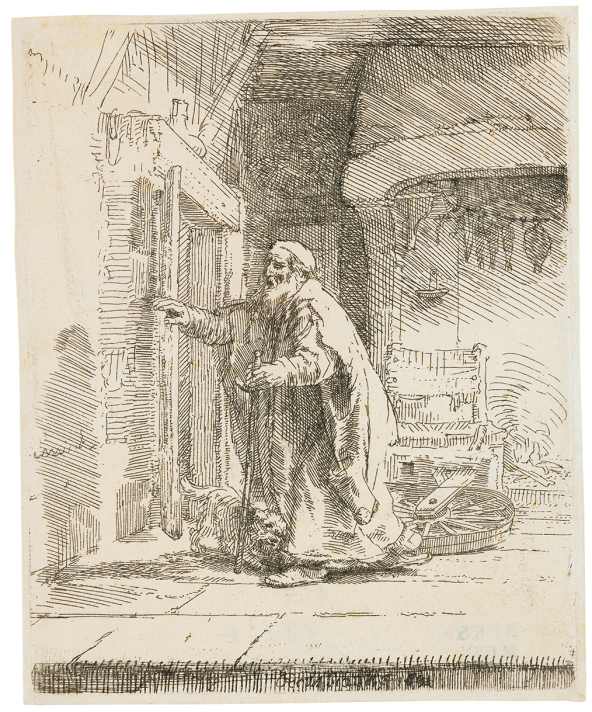

The story mostly recounts the tales of Tobit’s son, Tobias, who encounters various trials and hazards in a quest to retrieve a debt owed to his father in another city, and along the way finds a cure for his father’s blindness. In an etching dated 1651, Rembrandt touchingly shows Tobit getting up from his chair by the fire and tripping over his wife Anna’s spinning wheel when he learns that his beloved son had finally returned home Fig. 38.2.7

Rembrandt, The Blind Tobit: Large Plate, 1651. Etching on paper, 160 × 129 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-p-ob-293.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the etching, the old man wears a large overcoat and similar slippers to those seen here. In a drawing he made a few years later, Rembrandt depicted a seated Tobit wearing a similar tall cap while he addresses Anna, who has just brought home a goat Fig. 38.3.8

Rembrandt (or follower?), Tobit and Anna with the Goat, c. 1655 – 60. Pen and ink on paper, 146 × 185 mm. Berlin, Kuperstichkabinett, inv. no. KdZ 3090.

bpk Bildagentur/Kupferstichkabinett/Staatliche Museen/Berlin/Jörg P. Anders/Art Resource, NY

Rembrandt painted, drew, or etched many images of Tobit, and treated his story more than any other in the Bible throughout his career. 9

Although no hearth or description of Tobit seated by a fire features in the original biblical text, it had become conventional to show him this way. As early as 1626, Rembrandt had already begun his habit of depicting the blind Tobit seated by a fire.10

Later in his career, he innovated by showing an aspect of the story that was not previously treated, Tobit and Anna’s long wait for Tobias’s return. A painting in Rotterdam dated 1659 shows Tobit dozing by the hearth while Anna spins Fig. 38.4.11

Rembrandt (attributed to), Tobit and Anna, 1659. Oil on panel, 40.3 × 54 cm. Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv. no. VdV65.

Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Loan: Stichting Willem van der Vorm 1972. Photograph Studio Tromp

The biblical text reads: “Now Tobit his father counted every day; and when the days of the journey were expired, and they came not, then Tobit said ‘Are they detained?’ ” (Tobit 10:1 – 2).

As many commentators have remarked, the story must have held a deeply personal meaning for Rembrandt, whose own father was blind as an old man.12

Rembrandt may or may not have been planning one of his many images of Tobit when he made the Peck sketch, which depicts a figure whose gaze might be construed as distant but not necessarily blind. It nevertheless remains a pleasing study treating the uncomplicated act of warming oneself by a fire. Just the same, this commonplace pose could carry significantly greater emotional impact in Rembrandt’s hands when placed in a narrative context.

End Notes

Benesch 1954 – 57, vol. 2, 117, no. C26a (not reproduced). For the copy, see especially Sciolla 2007, 173 – 74, no. 135, with further references.

Benesch 1960, 154, no. 58; and Benesch 1973, vol. 5, no. 1153a. Benesch had previously thought the original to have been made around 1636, judging only from the copy, which is why he listed the copy in an earlier volume of his chronological corpus.

A good example of this is the series of changes in the position of the arms of the sick woman lying on the ground in the etching Christ Healing the Sick (The Hundred Guilder Print). Surviving sketches showing these changes are in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin; and the Clement C. Moore collection, New York. See Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, nos. D86, D87, D89; Schatborn 1985, no. 21; Bevers 2006, no. 40; and J. S. Turner in New York 2012, no. 31.

My thanks to Reba Snyder for sharing her thoughts on this issue. For Rembrandt’s various uses of white in his drawings, see G. J. Dietz and A. Penz in Bevers 2018, 297 – 98.

Benesch 1960, 154, no. 58.

Held 1964, 7.

Bartsch, no. 42; and New Hollstein (Rembrandt), no. 265.

Schatborn & Hinterding 2019, no. D163. While accepted by Schatborn, the drawing is listed as a work by an unknown member of Rembrandt’s school in Bevers 2018, 252 – 54, no. 132.

Held 1964, 7.

Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 6, no. 12.

Held 1964, 28.