Choose a background colour

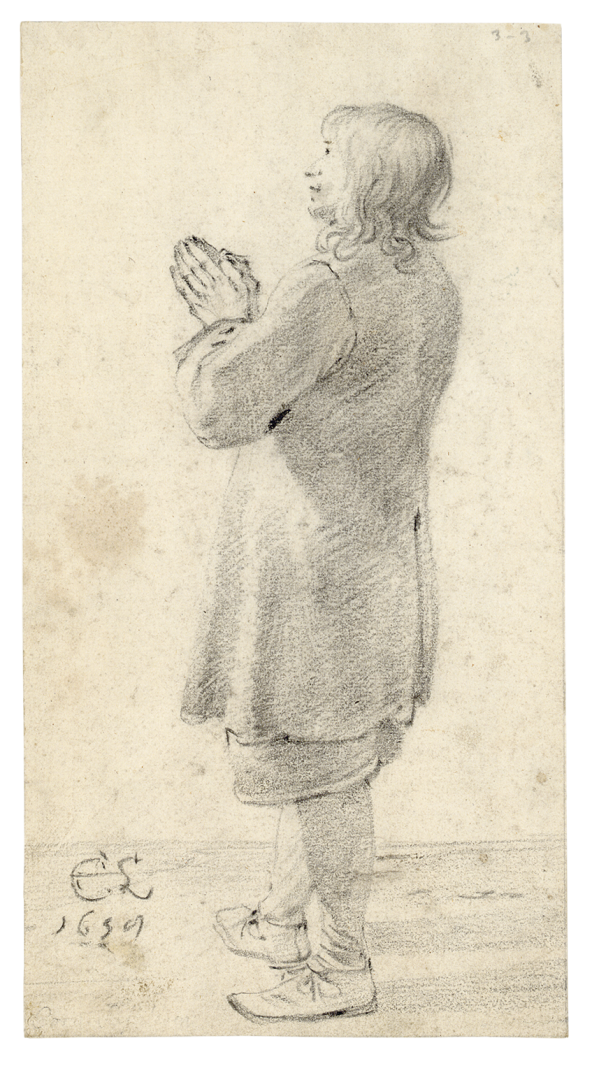

Cornelis Saftleven, Dutch, 1607-1681

:

Study of a Boy Carrying a Sack, 1654

Black chalk with highlights of white chalk on paper.

12 1⁄2 × 7 5⁄8 in. (31.8 × 19.3 cm)

Recto, lower right, in blackchalk, signed and dated by the artist with his monogram, CSL (in ligature) 1658; verso, lower right, in pencil, D 25800 HL.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 22 – 26 mm.

- Watermark:

- Double-Headed Eagle with Crown. Identical to Laurentius, vol. 2, no. 300A (Dordrecht, 1658).

- Provenance:

Prokop Toman, 1872 – 1927, Prague (Lugt 2401, stamp on verso); R. W. P. de Vries, Amsterdam, 1 – 3 November 1927; dealer, Colnaghi, London, June – July 1962 (cat. no. 25); dealer, Mortimer Brandt, New York, 1963; Lester Avnet, 1912 – 1970, New York (Lugt 5312); Sotheby Parke-Bernet, New York, 18 March 1978; Sotheby Parke-Bernet, New York, 3 June 1981, lot 71; Sotheby’s, New York, 18 January 1984, lot 184; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.75.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Schulz 1978, 107, no. 170.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.75

Cornelis Saftleven, like his equally long-lived younger brother, Herman Saftleven (1609– 1685), left behind a large body of drawings, many of which he signed and dated, and presumably offered for sale to collectors.1

While Herman moved to Utrecht as a young artist and established a career there as a landscape specialist, Cornelis remained in Rotterdam (where both brothers were raised), painting and drawing in a wide variety of genres. In terms of his drawn oeuvre, he is best known for his single figure studies like this one, which in total comprise about a third of his nearly 500 surviving sheets.2

The date on this drawing has sometimes been misread in auction catalogues as 1654, but Wolfgang Schulz correctly saw the last digit as an “8” in his study of the artist’s works.3

Saftleven regularly dated his drawings throughout his five-decade career, but the year 1658 was possibly a particularly active one for the artist as a draftsman, since more sheets bear this date than any other, some thirteen in total.4

Most of these are figure studies. In some of them, one can even recognize the same young model, who was likely a studio assistant, and can be found, for example, standing in prayer in a study in the Albertina Fig. 51.1.5

Cornelis Saftleven, Standing Young Man with Praying Hands, 1658. Black chalk on paper, 282 × 150 mm. Vienna, Albertina, inv. no. 9186.

Albertina, Vienna

The ultimate function of these numerous studies has resisted elucidation, since only a few have been identified as preparatory material for Saftleven’s paintings.6

The most notable of these is a painting in which the brothers teamed up, with Cornelis supplying the figure of a sleeping hunter and his dog, and Herman the landscape (cleverly signed in the plural, Saft-Levens).7

Most of his other unused studies he may have kept in the studio as potential stock for future work, or as records of drawing sessions in which he worked out specific problems and poses.

Given the large number of these figure studies that survive, however, and that the booming collectors’ market for drawings was on the rise in the 1650s, one cannot help speculating that many of these sheets were designed to be vendible from the outset. What impresses the idea further is the almost humorous way in which the boy carrying the sack peeks back at the artist under his lock of hair, seemingly focused less on his purported task than he is on the act of posing itself, an inflection that Saftleven may have even seized consciously. The sack itself comes across as little more than a pillowcase stuffed with a few articles, resting with improbable lightness across his head and shoulders, and thereby lending visible pretense to his stooped posture while stepping upward with a heavy load. One might be critical of Saftleven’s handling of a figure who is supposed to be under strain, but the proper “solution” to such an artistic problem might never have been the point in the first place. Arguably detected in the Albertina’s praying figure as well (and in other of his figure studies) is Saftleven’s seeming promotion of the idea that drawings can give the appearance of being studio material without ever really functioning as such, likely with collectors already in mind.

End Notes

For Saftleven’s life and works, see Schulz 1978.

Schulz 1978, 80 – 115, nos. 30 – 207. By far the greater majority of these depict male figures, though Schulz also catalogued twenty-eight female figures.

Schulz 1978, 107, no. 170. The drawing is often found listed with the earlier date in the dealer and auction catalogues listed in the Provenance, above.

For a complete list of Saftleven’s dated drawings, see Schulz 1978, 265.

Schulz 1978, 102, no. 144.

Schulz gives periodic examples in his general discussion of the drawn oeuvre; see Schulz 1978, 40 – 67.

See the entries by W. W. Robinson in Washington & Paris 2016 – 17, 175 – 77, nos. 68 – 67; and Amsterdam, Vienna, New York & Cambridge 1991 – 92, 158 – 59, no. 70.