Article: Undergraduate Research and the Peck Collection

Focus on the Peck Feature

The four drawings on display are amongst those studied in detail by undergraduate students in UNC-Chapel Hill’s Department of Art and History in the fall semester of 2017. Fifteen students in the Art History Undergraduate Research Seminar proposed new interpretations and understandings of fifteen of the Peck Collection drawings. The students had many opportunities to view the drawings up close, and they even had the chance to meet and share their findings with Dr. Sheldon Peck, who visited the seminar in October 2017. In their research, the four students whose drawings have been selected for this exhibition made important discoveries.

The four drawings in this display were amongst those studied in detail by undergraduate students in UNC-Chapel Hill’s Department of Art and History in the fall semester of 2017. Fifteen students in the Art History Undergraduate Research Seminar proposed new interpretations and understandings of fifteen of the Peck Collection drawings, which had been given to the university just six months earlier. The students had many opportunities to view the drawings up close, and they even had the chance to meet and share their findings with Dr. Sheldon Peck, who visited the seminar in October 2017.

In their research, the four students whose drawings have been selected for this exhibition made important discoveries. Through an extensive series of comparisons to works by other Rembrandt students, Anselme Long, a Junior art history major, was able to identify the studio setting in which this drawing was made. Emily Edgerton, another Junior art history major, through detailed analysis of the perspective of this drawing, explored Thomas Wyck’s early focus on ruinous Italian buildings. Senior art history major Ori Erna Hashmonay worked out the precise Jewish community represented in Koninck’s procession. Jeremy Howell, who is a Senior double majoring in art history and history, analyzed Rembrandt’s straightforward, yet sensitive, depiction of an African servant in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.

Each drawing is delightful in its own right, but learning so much more about them has deepened our appreciation and enjoyment of them.

Dr. Tatiana C. String, Associate Professor of Art History

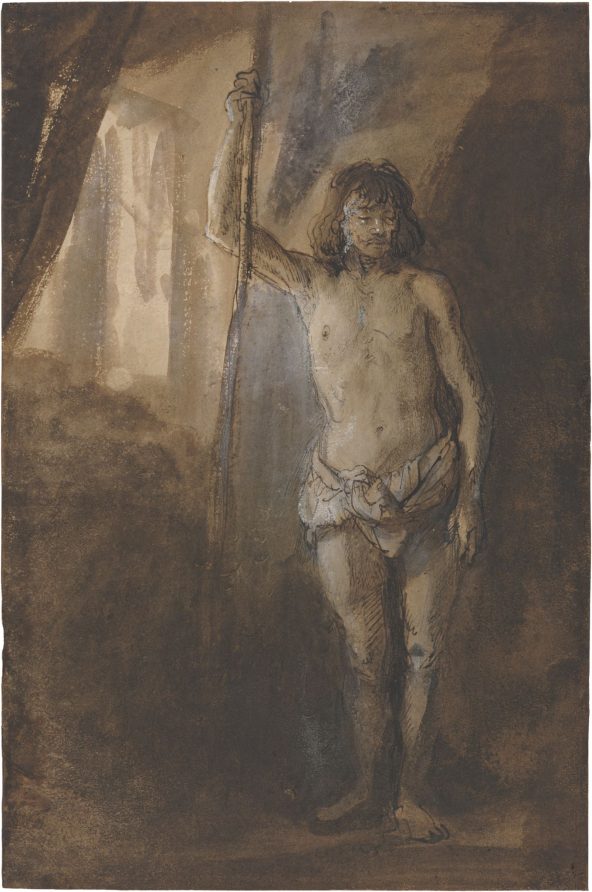

Standing Male Nude Holding a Staff

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Dutch, 1627 – 1678, Standing Male Nude Holding a Staff, c. 1646. pen and brown ink with brown wash on paper. The Peck Collection, 2017.1.43

See Standing Male Nude Holding a Staff in more detail here.

Samuel van Hoogstraten created Standing Male Nude Holding a Staff around the time of his tutelage under Rembrandt van Rijn. The study is closely related to a series of drawings and etchings created by Rembrandt and his students in 1646, a significant moment in Rembrandt’s teaching career as it falls in a period in which he was keen on his students drawing nude models. In the studio, Rembrandt worked alongside his pupils, often drawing the same model holding the same pose. Through comparisons between work done by Rembrandt and that of fellow students, this drawing grants insight into Rembrandt’s ideas on drawing principles, notions of artistic imitation, and conceptions of the nude.

Anselme Long

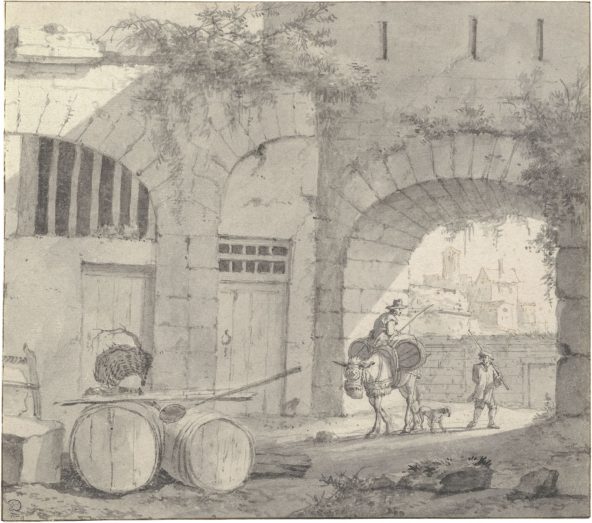

A Courtyard in Italy

Thomas Wyck, Dutch, 1616 – 1677, A Courtyard in Italy, c. 1640-50, brush and gray wash over black chalk on paper. The Peck Collection, 2017.1.98

See A Courtyard in Italy in more detail here.

Thomas Wyck was a member of the so-called Bamboccianti, a group of Dutch artists who traveled to Italy during the 1600s to gain exposure to the Italian art world. Unlike many of their contemporaries who romanticized depictions of the Italian landscape and Roman monuments, Wyck and the Bamboccianti showed all aspects of Italian life. In this drawing, Wyck highlights the crumbling architecture of the courtyard and the frayed basket, which illustrate the everyday setting of the majority of Italians. While the perspective in this work is not precise, Wyck captured the essence of Italy.

Emily Edgerton

A Jewish Funeral Procession

Philips de Koninck, Dutch, 1619 – 1688, A Jewish Funeral Procession, c. 1660, pen and brush and brown ink on paper. The Peck Collection, 2017.1.47

See A Jewish Funeral Procession in more detail here.

Philips de Koninck created A Jewish Funeral Procession, a sketch perhaps prompted by the newly congregated Ashkenazi Jewish community in Amsterdam, in the late seventeenth century. The arrival of the Ashkenazi Jews marked a watershed after various pogroms had led the community to seek religious asylum in the northern Netherlands between 1630 and 1640. Wearing caftans, tall hats lined with fur, and berets, and having untrimmed beards, the appearance of the Ashkenazi community was easily identifiable, as seen in A Jewish Funeral Procession. In this ink-wash drawing on paper, Koninck emphasizes the garments worn by the figures in the procession with meticulous and precise shading techniques. There are seventeen figures in total; the men to the far right of the composition wear tall, mitre-like hats, have beards, and are adorned in caftan robes while carrying staffs.

Ori Erna Hashmonay

Study of a West African Woman

Attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 – 1669, Study of a West African Woman, c. 1635, pen and brown ink on paper. The Peck Collection, 2017.1.62

See Study of a West African Woman in more detail here.

Study of a West African Woman offers insight into how Rembrandt viewed contemporary Africans living in the Netherlands. Drawn with fewer than sixty lines, the sketch depicts a woman toting a chicken under her left arm, having been to the market. The woman was probably one of the many African servants in Amsterdam who lived in a gray area between enslavement (which was not legal in Holland) and freedom. Contrary to many contemporaneous Dutch artists, Rembrandt attempted to humanize his African subjects. The sketch exemplifies Rembrandt’s lifelong pursuit in depicting Africans as they truly were, which culminated in his painting Two Moors (Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands) from 1661.

Jeremy Howell