Choose a background colour

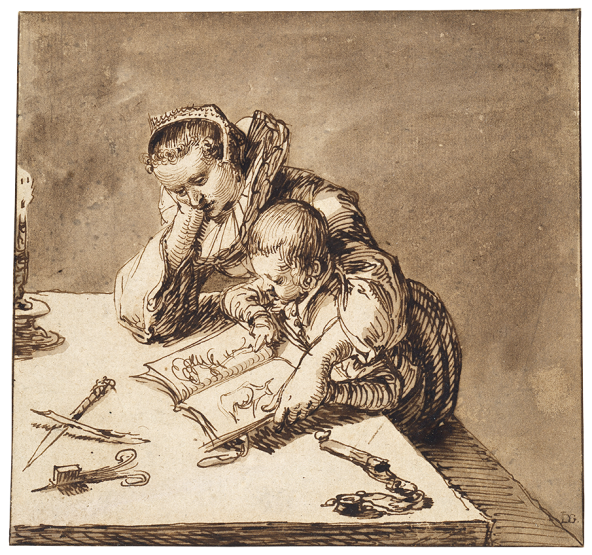

Jacques de Gheyn II, Dutch, 1565-1629: Young Man Writing at a Table (The Artist’s Son), c. 1605-10

Black chalk on paper

6 1⁄2 × 5 11⁄16 in. (16.5 × 14.4 cm)

Recto, signed in black chalk on the boy’s writing paper, IDGheyn.in. (the first three letters in ligature); verso, lower left corner in brown ink N212, in pencil, j.

- Chain Lines:

- Horizontal, 25 – 26 mm.

- Watermark:

- None

- Provenance:

Probably Arnout Vosmaer, 1720 – 1799, The Hague; sale, Van Balen, The Hague, 7 November 1754, lot 69 (Een mannetje aan een Tafel tekenende; sold 1.2 guilders to Van Duysel); private collection, England; I. Q. van Regteren Altena, 1899 – 1980, Amsterdam (Lugt 4617, stamp on verso of backing sheet); his sale, Part II, Christie’s, Amsterdam, 10 December 2014, lot 123; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.36.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

J. Giltaij in Rotterdam, Paris & Brussels 1976 – 77, no. 59; Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 107 – 08, no. 674, vol. 3, 159, pl. 309; J. A. Poot in Rotterdam & Washington 1985 – 86, 67, no. 58; Kuretsky 2017, 6, fi g. 5.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.36

With pen in hand and drawing instruments on the table, the artist’s son sits in a thoughtful pose. Above the sweeping mark on the page, he has written “JD Gheyn in,” the name he shares with his father. The abbreviation “in” stands for “inventor” and indicates the author of a design. In this instance, it cleverly reveals Jacques de Gheyn II as both the drawing’s creator as well as the maker of his son. Although the sheet depicted is signed, it remains incomplete, suggesting the perseverance and patience required during this early stage of invention.

Jacques de Gheyn II was one of the most prolific and eclectic draftsmen of his day, whose works continue to fascinate for their range of iconography and frequently open-ended potential for interpretation.1

This drawing gives every appearance of being a strikingly casual portrait of the artist’s only child, Jacques de Gheyn III (1596 – 1641), who would go on to become a noted artist in his own right and his father’s closest follower.2

Despite its ostensible simplicity, however, one can find layers of meaning in this drawing that are in keeping with De Gheyn’s obvious wit.

The young man leans intently over a small table with an inkwell and a selection of pens as he contemplates a sheet of paper on which he has evidently just written JDGheyn in. This is a form of signature that both father and son used on their artworks. In this case it serves as a clever means for the father to sign the sheet, which he does upside down to make it appear as if his son had just signed it.3

The abbreviation “in.” for inventor was a standard suffix at the time, used to designate the artist as the specific creator of the design. It was especially used by printmakers (painters more frequently signed with a form of fecit, or “made it”) to clarify who originally drew or painted the image. Since the sitter’s father trained and worked as an engraver for the first half of his early career (before turning to painting), its use would appear perfectly conventional at first glance. There is a delightful irony, however, that must have surely been intentional: the father did not just create this informal portrait of his son, he was also his son’s “inventor,” both in the sense of artistic birth and in the sense of being actual progeny. At the same time, by showing his son in a creative moment, De Gheyn also acknowledged his offspring’s own considerable creative impulses and talent, which were recognized at an early age in the writings of his father’s good friend, Constantijn Huygens I (1596 – 1687).4

This drawing belonged to the noted collector and art historian I. Q. van Regteren Altena (1899 – 1980), whose three-volume monograph on the De Gheyn family remains the standard study of the artists.5

This particular sheet must have held special importance to the great scholar of the life and art of both father and son. Van Regteren Altena appears to have been the first to suggest that De Gheyn depicted his son in this drawing.6

This is a good supposition, though incontrovertible confirmation of his identity through comparisons with other known or supposed likenesses is elusive.7

Some of Van Regteren Altena’s other identifications of the younger De Gheyn in his father’s drawings have rightly been criticized.8

The only secure likeness of the son actually comes from the hand of Rembrandt, who appears to have been a friend of his, and who painted the small portrait now in the Dulwich Picture Gallery dated 1632 when he would have been around thirty-six years old Fig. 3.1.9

Rembrandt, Portrait of Jacques de Gheyn III, 1632. Oil on panel, 29.9 × 24.9 cm. London, Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv. no. dpg99.

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Despite the age difference, the comparison of likenesses seems to hold up well enough. This painting was subjected to relentless (and one assumes lighthearted) mocking, however, by Contantijn Huygens for its lack of resemblance to the younger De Gheyn. In one of the few surviving instances of a jocular response to a painting by a major Dutch artist at the time, Huygens composed no fewer than eight Latin epigrams teasing the painter he so admired (“This is the hand of Rembrandt, the face of De Gheyn; look in wonder, reader, it also is not the face of De Gheyn”).10

In the end, perhaps the best argument that the drawing indeed depicts the artist’s son is the nature of the composition itself: the signature faces inward, and the wit holds up.

If the young man in the drawing is his son, and in his early to mid-teens, then we can date the sheet to around 1605 – 10.11

De Gheyn executed most of his drawings with pen and ink, though in this work he demonstrates a great facility with chalk, which he seems to have employed for less formal drawings, and which he used here with flourish and a broad range of stroke.12

Although signed, we can speculate that it would have nevertheless remained in the family since the signature is, in a real sense, integral to the concept of the composition. Van Regteren Altena surmised that De Gheyn found inspiration in both technique and composition in a drawing by Lucas van Leyden (1494 – 1533) from around 1512 plausibly known to him Fig. 3.2.13

Lucas van Leyden, Man Drawing or Writing, c. 1512. Black chalk on paper, 272 × 272 mm. London, British Museum, inv. no. 1892.8.4.16.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The man in Lucas’s sheet appears to be drawing rather than writing (although previous scholarship emphasizes the latter).14

Such compositional similarity might purely be coincidental, but Lucas did enjoy an enormously high reputation among Dutch artists of the early seventeenth century, and De Gheyn also copied some of his prints.15

Aside from the theme of an artist and his progeny, there are also reasons to suspect a deeper, more allegorical meaning behind this drawing.16 Hints of such a possibility have been noted in other drawings by De Gheyn, such as Berlin’s Mother and Child Looking at Pictures Fig. 3.3.17

Jacques de Gheyn II, Woman and Child with a Picture Book, c. 1600 – 05. Pen and brown ink with brown wash on paper, 137 × 148 mm. Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. no. KdZ 2680.

bpk Bildagentur/Kupferstichkabinett/Staatliche Museen/Berlin/Volker-H. Schneider/Art Resource, NY

While striking as a prosaic genre subject, Hessel Miedema asserted that the Berlin drawing’s main purpose was actually to allegorize the process of learning.18

In Aristotelian thought, learning is the product of instruction, practice, and natural aptitude, all three of which can feasibly be located within the image: the mother (a source of natural aptitude) offers instruction, and the boy, although too young for practice, faces the scattered writing implements that imply his future endeavors in this regard.19

Another drawing by De Gheyn, even more clearly allegorical, depicts a young man with writing implements gesturing toward a candle or lamp (also just visible in the Berlin drawing), which are traditional symbols of study and practice Fig. 3.4.20

Jacques de Gheyn II, Young Man at a Table with a Candle, c. 1610 – 12. Pen and brown ink on paper, 135 × 103 mm. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, inv. no. 1961.63.79.

Yale University Art Gallery

While the loosely sketched background in the present sheet does not offer a clear consideration of his chamber or surroundings, one does at least detect the semblance of a candle or lamp emitting light in the background on the right, from a source on a shelf just over the sitter’s shoulder. With the artist’s hand supporting his head, and his eyes seemingly unfocused, De Gheyn here arguably represents a mind engaged in the creative process, and therefore emblematizes the practice required for those in the apprentice stage to attain mastery. There is an ineluctable irony in the fact that the sheet before him appears empty (but for a long diagonal flourish) and yet has been signed invenit, as if the production was complete.

A different sort of irony can be found in the autobiography of Constantijn Huygens, who wrote how disappointed he was that the younger De Gheyn wasted hours in idleness instead of using his astonishing talent as “an adornment to his fatherland.” Huygens singled out his drawing ability in particular: “[De Gheyn] has already, although he has not yet left his boyhood behind him, furnished such brilliant evidence of his talents, both in drawing with the pen and [chalk] crayon, and to some extent also in painting, that to the amazement of his contemporaries he already equals the great masters…” but, Huygens continues, “I am unable to conceal my vexation at it being possible for these beginnings, through indifference, to result in so very little.…Until now I believed that Poverty alone could stand in the way of talent, but now it is also choked by too much prosperity.“21

Huygens’s notion that Jacques de Gheyn III was a spoiled child should perhaps be taken with a grain of salt, but, whatever the case, his interest in making art indeed dropped precipitously after the death of his father in 1629. He ultimately left behind only a small handful of paintings, drawings, and prints.

End Notes

For Jacques de Gheyn II, see especially Van Regteren Altena 1983; as well as Van Regteren Altena 1936 (the trade edition of his dissertation from 1935, translated into English); Judson 1973; Paris 1985; and Rotterdam & Washington 1985 – 86.

For Jacques de Gheyn III, see especially Van Regteren Altena 1983.

For other examples of “signing” inscriptions, see Kuretsky 2017, 6, and fig. 5 for the present sheet (incorrectly described as signed with IDGheyn III in. instead of IDGheyn in.).

Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 1, 159 – 60.

Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 107, no. 674 (“A boy, probably J. de Gheyn III, seated at a table”); though see the entry by Jeroen Giltaij in Rotterdam, Paris & Brussels 1976 – 77, 34, no. 59, who also identifies the young man as the artist’s son for the exhibition of Van Regteren Altena’s collection, a suggestion that appears to have originated from the owner.

For other likenesses of Jacques de Gheyn III identified by Van Regteren Altena in the corpus of his father’s drawings, see the Family Portrait in the Fondation Custodia, Paris (Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 106, no. 669; the idea rejected in Boon 1992, vol. 1, 174 – 76, no. 93; see also C. van Hasselt in Paris 1985, 58 – 61, no. 22); and the Portrait of a Boy in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (Van Regteren Altena 1983, 107, no. 673; A. W. F. M. Meij in Rotterdam & Washington 1985 – 86, 53, no. 33; Boon 1978, vol. 1, 80, no. 228).

See Schapelhouman 1988, 265 – 66, in a review of Van Regteren Altena 1983.

For Rembrandt’s painting, see Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 2, 219 – 24, no. A56; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, 162 – 64, no. DPG99; and Van de Wetering 2017, vol. 1, 514, no. 68, vol. 2, pl. 68.

These epigrams, written in Latin by Huygens in 1633, can be found in translation in Bruyn et al. 1986 (Corpus vol. 2), 223, under no. A56.

A date of circa 1609 – 10 proposed by Van Regteren Altena is based on the apparent age of the sitter as fifteen or sixteen years old, if indeed he is Jacques de Gheyn III. Accepting the latter supposition, we might broaden the date range slightly to a few years on either side of 1610.

See also the black chalk studies in the Teylers Museum; Bleyerveld & Veldman 2016, 63 – 65, nos. 46 – 47 (with also the suggestion that chalk might be used for “more informal works”); and Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, nos. 691 – 92.

Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 107 – 08, no. 674; mentioned also by J. Giltaij in Rotterdam, Paris & Brussels 1976 – 77, 34 – 35, no. 59.

For the drawing by Lucas van Leyden, see the entry by W. Kloek in Leiden 2011, 296, no. 89; and Kloek 1978, 442, no. 6.

See, for example, Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, nos. 1041 – 44.

This question was first raised in the entry on the present sheet by J. A. Poot in Rotterdam & Washington 1985 – 86, 67, no. 58.

For this drawing, see Bock & Rosenberg 1930, vol. 1, 30, no. 2680, vol. 2, pl. 23; and Holm Bevers in Berlin 2011 – 12, 22 – 23, no. 2.

See Miedema 1975.

Idem.

For this drawing, see Haverkamp Begemann & Logan 1970, 207 – 08, no. 379, who pointed out the allegorical implications; and Miedema 1975, 12 (and fig. 4), who suggested that it may have belonged to a series with the Berlin drawing, though this suggestion seems less plausible than De Gheyn simply repeating an interest in allegorizing the subject of drawing on separate occasions.

Cited and translated in Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 1, 159 – 60.