Choose a background colour

Guillam Dubois, Dutch, 1623/25-1653: View of Noordwijkerhout, with the Witte Kerk, c. 1646-50

Gray wash and red chalk over traces of black chalk on paper; framing lines in brown ink.

4 1⁄2 × 7 3⁄8 in. (11.5 × 18.8 cm)

Recto, upper left, in pen and ink, annotated (likely by the artist) in a seventeenth-century hand, noortwykr hout; verso, lower center, in pencil, Noortwyker hout, and lower left, za f 880.8 f14-.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 22-23 mm.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Dealer, C. G. Boerner, Düsseldorf, 1962; dealer, Bernard Houthakker, Amsterdam, 1965, cat. no. 57; sale, Sotheby Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 3 May 1976, lot 101; sale, Christie’s, Amsterdam, 15 November 1993, lot 100; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.22.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Giltaij 1977, 159 (note 50); F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 46 – 47, no. 6.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.22

Little is known about Haarlem-based artist Guillam Du Bois apart from his entry into the artists’ guild in 1646, his voyage to Cologne with two fellow artists from 1652 to 1653, and his small body of extant work.

This view of Noordwijkerhout, located between Haarlem and Leiden, showcases the village’s Witte Kerk (White Church), which had recently undergone selective restorations. Although parts of the nave and the apse were intentionally left in ruins at the time, Du Bois focused on the refurbished sections. As in his drawing Cottages Along a Wooded Road, c. 1647, Du Bois applied touches of red chalk to both enliven the scene and add subtle texture to the charming and rustic buildings.

The View of Noordwijkerhout highlights Du Bois’s ability to work in a combination of media, here using a fi né-tipped brush to create foliage effects as distinctive as those found in his black chalk drawings, but likewise adding touches of red chalk to lend the image a subtle liveliness and sense of perspectival variety. A closely related sheet in terms of size, technique, and subject matter is his View of the Church at Soest in the Rijksmuseum Fig. 31.1.1

Guillam Du Bois, View of the Church at Soest, c. 1648 – 53. Black and red chalk with gray wash on paper, 130 × 198 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-t-1976-115.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Both drawings bear early inscriptions that correctly identify the sites, prominently in the Peck drawing in the upper left corner (and on the Rijksmuseum’s sheet partially cut off in the upper right). These may have been written by the artist himself, or certainly at some point in the seventeenth century. The inscriptions probably reflect separate journeys since the two locations lie in considerably different directions from Du Bois’s hometown of Haarlem.

To reach Noordwijkerhout, the artist traveled south from Haarlem toward Leiden, where he would have encountered the village somewhere around the midpoint between the two cities. Jan van Goyen (1596 – 1656) also depicted Noordwijkerhout on at least two occasions, once in a still-intact sketchbook from the late 1640s (the Bredius-Kronig sketchbook), and another time from a farther vantage point in a monogrammed black chalk drawing dated 1653 Fig. 31.2.2

Jan van Goyen, View of Noordwijkerhout, 1653. Black chalk with gray wash on paper, 116 × 195 mm. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. no. pd.364-1963.

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The village may have been more easily accessible around this time, since the trekvaart (the popular passenger boat canal service) expanded rapidly in the 1630s and 1640s throughout the province of Holland, including between Haarlem and Leiden.3

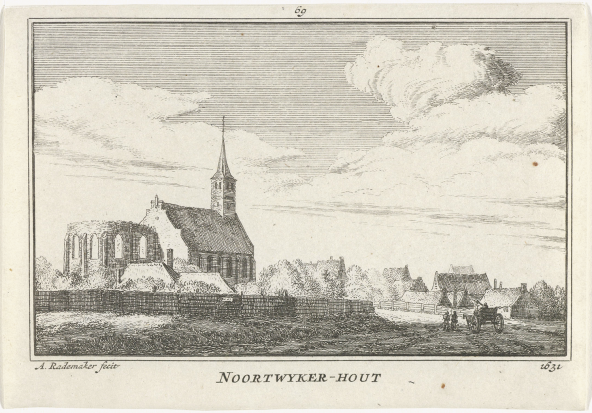

Du Bois and Van Goyen, however, do not appear to be the first artists to take an interest in the village. Abraham Rademaker recorded now-lost views of Noordwijkerhout made in 1631 and 1634 that he reproduced as etchings nearly a century later in his Kabinet van Nederlandsche outheden en gezichten, published in 1725 Fig. 31.3.4

Abraham Rademaker, after an unknown artist, View of Noordwijkerhout (after a lost image from 1631), book illustration for Kabinet van Nederlandsche en Kleefsche outheden, 1725. Etching on paper, 80 × 115 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. R P-P-OB-73.422.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Today, the town sits in the middle of the famous bollenstreek (bulb region), where crowds of tourists descend each spring to view tulips. While tulips were of course well-known in the seventeenth century, most of the tulip-growing fields in this region only came much later, after the many woods had been cleared.

The Witte Kerk (or “White Church”) appears much the same today as it did in Du Bois’s time Fig. 31.4.

The Witte Kerk at Noordwijkerhout (photo by the author, January 2019).

Robert Fucci

This medieval parish church was founded in the early thirteenth century, but suffered near-total destruction during the Eighty Years’ War at the hands of Spanish troops during one of their failed sieges of Leiden in 1573 – 74.5

Repairs were undertaken between 1618 and 1620 that rendered it into the more modest structure seen in the present sheet.6

Having no pastor, the Witte Kerk fell into disuse in the early seventeenth century, and villagers complained that they had to share a pastor in Voorhout. The church became active again right around the time Du Bois likely made this drawing.

In 1647, Calvinist church authorities finally assigned Noordwijkerhout its own predikant and ordered further restorations to the Witte Kerk.7

The apse and much of the nave were intentionally left in ruins, as one sees in Van Goyen’s and Rademaker’s images, though Du Bois decided to focus instead on the restored portion of the church, offering only the slightest suggestion of the lower wall of the ruins behind (just visible through the trees at the far right). Perhaps he preferred to reflect on the rustic calm of a village seemingly untouched by time. As Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne recorded in his journal when he traveled with Du Bois to Cologne in 1652, they passed “over 300 villages with bell towers and parish churches.“8

While this drawing may have been made before that trip, Du Bois’s captivating appreciation of the charming hamlets in the more rural regions of the country is clear.

End Notes

Schapelhouman & Schatborn 1987, no. 66; and P. Schatborn in Amsterdam 2014, 145 – 46, no. 50.

For the Bredius-Kronig sketchbook drawing, see Beck 1972 – 91, vol. 1, 266, no. 845/23; and Buijsen 1993, 47 – 48, no. 23. For the 1653 drawing, see Beck 1972 – 91, vol. 1, 162, no. 480. For a third drawing by Van Goyen thought to depict Noordwijkerhout, though differences in the steeple and nave wall architecture of the church cast some doubt, see D. Scrase in Munich, Heidelberg, Braunschweig & Cambridge 1995 – 96, no. 12; and Beck 1972 – 91, 247, no. 819 (the latter leaving the issue of identification aside).

Brouwer & Van Kesteren 2008, 45 – 85.

Rademaker 1725, vol. 2, 119 – 20, nos. 69 – 70

For the history of the Witte Kerk, see Ter Kuile 1944; Van Agt 1951; Berghuis 1972, 57 – 58; Bitter 1988; and Rinzema et al. 2000.

Ter Kuile 1944, 170, citing a document from 1618, “te doen repareeren” the “ruineus liggende” church. The restoration essentially returned the church to its original but smaller Romanesque footprint, with the Gothic expansions made in the apse from circa 1500 essentially left in ruins. This was not an exceptional circumstance; the church at Zandvoort also went through a “nave-only” restoration around this time as well

Van de Roemer-Bosman in Rinzema et al. 2000, 61 – 73. Apparently, many of the villagers had been reverting back to Catholicism since they could then be tended by the traveling monks who often roamed the Northern Netherlands precisely for the purpose of offering sacraments to overlooked communities, and to reconvert them.

Sliggers 1979, 48: “over 300 dorpen met klock toorens en parochij kercken.” The description comes from the stage of their journey that passed through Gelderland on their way to Germany in 1652.