Choose a background colour

Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Dutch, 1598-1657

:

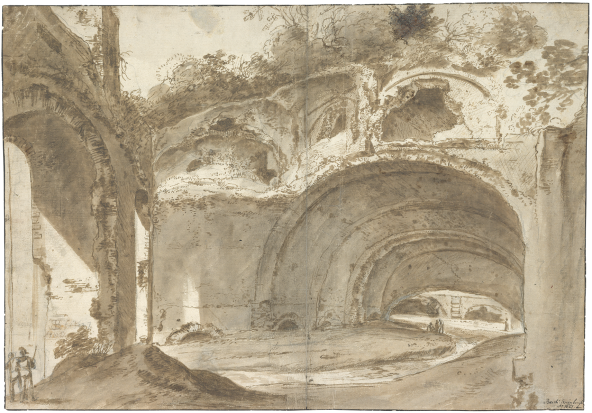

View from Inside a Vaulted Chamber, Possibly the Villa of Maecenas in Tivoli, 1657

Brown and gray wash with additions in black chalk on paper; framing lines on left, right, and top in brown ink.

10 1⁄4 × 8 7⁄16 in. (26.1 × 21.5 cm)

Recto, lower right, signed and dated in pen and brown ink (the date cropped), Bartholomeäs Breenborch.f / Ao 1627 (presumed date, third digit difficult to discern); verso, lower center, in pencil, Ecole hollandaise, Deventer-/Bartholomé Breengergh actif vers. 1629 – 1660, upper right, V.37 / 21651⁄37.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 30 – 32 mm.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Unidentifi ed collector’s mark RVZS[?] (stamp on verso, gray ink); Einar Perman, 1893 – 1976, Stockholm; sale, Sotheby’s, London, 27 June 1974, lot 117; dealer, Richard L. Feigen, New York, 1991; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.13.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Stockholm 1953, 54, no. 160; Roethlisberger 1991, 78 – 79, no. 31; M. Roethlisberger in Lugano 1998, 320 – 21, fi g. 4; F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 40 – 41, no. 3; E. Brugerolles & A. Castres in Paris & Ajaccio 2014 – 15, 62 – 65, under no. 18, fi g. 2 (captioned as fi g. 1).

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.13

Landscape painter Bartholomeus Breenbergh found inspiration in the natural and human-made tunnels, caverns, and vaults he encountered while living in Italy during the 1620s. The large, broad vault here appears to be one of the chambers found in the lower level of what Breenbergh and his contemporaries believed was the Villa Maecenas in Tivoli, now identified as the Sanctuary of Hercules Victor. Bold in its execution, this drawing was produced almost entirely with varying shades of wash, or diluted ink. The dark, cool atmosphere of the interior space encompasses most of the composition, yet the focus of the work rests on the sunshine and warmth just beyond the large entryway.

Signed with one of Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s most prominent signatures, this drawing offers an evocative sense of the cooled interior of a large vault on a sunny day. Marcel Roethlisberger called it a stunning sheet, its powerful composition creating “a mysteriously resounding hollow space.”1

The setting is no doubt Italy, drawn from Breenbergh’s experiences there in the 1620s. In several of his drawings of ancient ruins, he explored viewpoints from just within the structures showing an open-air prospect, and used innovative compositional formulas and perspectively rich schemes to create bold contrasts between inside and outside.2

Some other noteworthy examples dated 1627 can be found in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Fig. 9.1,Fig. 9.2.3

Bartholomeus Breenbergh, View in the Colosseum in Rome, 1627. Brush and pen in brown ink over black chalk or graphite, 236 × 175 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. rp-t-1989-91.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Roman Ruins (“Coliseo”), 1627. Brush with brown and gray wash over black chalk or graphite, 238 × 184 mm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 1983.410.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Francis Welch Fund and Lucy Dalbiac Luard Fund

Breenbergh’s subtle application of brown and gray washes in these works is the key to their effectiveness in terms of modulated lighting and a perceptible sense of surface and texture.

The Amsterdam drawing clearly depicts the Colosseum in Rome, and the Boston drawing probably a vault from the same, indicated by an early inscription on the verso. An identification of the site in the present sheet, however, has not been argued in the previous literature. The large, broad vault appears to be one of the “stables” found in the lower level of the Villa of Maecenas in Tivoli, now properly understood to be the Sanctuary of Hercules Victor.4

Due to the massive size of the complex, it was long assumed to have been a villa rather than a temple, but it served a variety of functions over the centuries. In Breenbergh’s day it was part of the pontifical armory from 1612 onward.5

Immense structural changes to the site over the years have been too drastic, unfortunately, to identify with certainty exact locations within the complex. From many of his other drawings of the area, we can nevertheless state with confidence that Breenbergh was indeed in Tivoli at some point.6

He depicted the town and its waterfalls, and the famous Temple of the Sibyl that had already long been a favorite subject of artists. He also appears to have used the vaults of the Villa of Maecenas in another drawing, the impressive sheet in the Fondation Custodia monogrammed and dated 1627 that Rembrandt pupil Philips Koninck (1619 – 1688) described as being one of the artist’s best Fig. 9.3.7

Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Roman Ruins in Tivoli, 1627. Pen and brush in brown ink over black chalk, 352 × 505 mm. Paris, Fondation Custodia, inv. no. 3032.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

More open to the sky, it shows figures under a broad vault with a stream or ditch running through the middle, similar to the one faintly visible in the Peck sheet, though a different vault.

These works illustrate how Breenbergh innovated in finding engaging viewpoints, and in applying washes in creative ways to suggest light and texture. Most artists making drawings in Rome focused on ancient monuments as discrete works of notable architecture in their own right, or (if not clearly identifiable monuments) on Roman architecture generally as a high point of ancient culture. On occasion, Breenbergh focused instead, as here, on the experiential nature of such structures, finding viewpoints that enhance one’s sense of direct personal presence, and that facilitate a sense of wonder through tangibility rather than framing the architecture with a documentary eye. The almost claustrophobic sense that Breenbergh manages to impart in this drawing enhances the awesome grip of ancient architecture in a manner that could be said to anticipate, to some degree, the famous prints and drawings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720 – 1778).

There has been some debate over the date of this drawing, whether 1627 or 1657, since the year written below the signature is almost entirely cropped. Roethlisberger declared the latter date impossible given the Italian subject matter and the variant spelling of his name as Breenborch instead of Breenbergh, but neither argument is convincing in itself.8

Breenbergh was in the habit of making replica drawings of his Italian subjects after he returned to the Netherlands in 1629.9

He also used slight variations of the spelling of his name throughout his career.10

Franklin Robinson argued the date as 1657, putting the drawing in the last year of the artist’s life.11

Indeed, it is easier to read the top part of the third digit as that of a “5.” The earlier date of 1627, however, is certainly the correct one. His other distinctive vault interior drawings discussed above bear autograph dates of 1627.12

Breenbergh signed his full name (rather than monogrammed or abbreviated) on only four other known sheets, and each of these also bears the year 1627.13

He occasionally made slips of the pen or flourishes on his digits, something that better accounts for the strange appearance of the top of the third digit here.14

Furthermore, the subject matter and signature of his one known drawing from 1657 are entirely dissimilar.15

A closely related drawing attributed to the British artist Francis Place (1647 – 1728) recently came to light Fig. 9.4.16

Francis Place, A Grotto (The Stables of the Villa Maecenas, Tivoli?), c. 1700. Pen and brown ink with brown wash over graphite, 189 × 340 mm. Washington, National Gallery of Art, inv. no. 2018.175.2.

National Gallery of Art, Washington. William B. O’Neal Fund

It appears to be based on the Peck drawing, with its right half matching Breenbergh’s in composition and scale, but with the flatter and more ambiguous appearance of a copy. Place’s authorship is assumed based on its appearance in a group with all of his other known drawings, sold by a family descendent in 1931.17

The copy is important for revealing what may have been the larger extent of Breenbergh’s composition. Drawings from his Italian period could be quite large and even double the size of the present sheet. The Peck drawing was possibly cut down significantly at some point, which would account for the cropped nature of the left edge of the composition. It might also be a partial replica by Breenbergh himself. That he was apparently in the habit of making partial copies of his own works is revealed by a drawing in Chicago that precisely reproduces the left half of the aforementioned Villa of Maecenas in the Fondation Custodia.18

Whatever the case, one cannot help wondering if the original composition was once much larger.

End Notes

Roethlisberger 1991, 78.

For some other examples, see Roethlisberger 1969, nos. 12, 101, 113, 152, and 161; and the works illustrated (including the present sheet) in Paris & Ajaccio 2014 – 15, under no. 18.

For the Amsterdam drawing, see Schapelhouman & Schatborn 1998, no. 77; the signature and date have faded considerably but remain legible enough to confirm they are by the artist’s hand. The Boston drawing bears an autograph monogram and date.

The site has changed much, but for its treatment by some other (mostly eighteenth-century) artists, see Cogotti 2014, 29 – 32; and for its architecture generally, Giuliani & Ten 2016.

For Breenbergh in Tivoli, see especially Alsteens 2015. For other drawings set in or around Tivoli, see Roethlisberger 1969, nos. 45, 52, 87 (as Cornelis van Poelenburch [1594/95 – 1667], but actually Breenbergh; see Dresden & Vienna 1997 – 98, no. 78), 97, 98, 102, 104, 112, and 114.

Roethlisberger 1969, no. 104; and Brussels, Rotterdam, Paris & Bern 1968 – 69, no. 26. See also Chicago 2019 – 20, 241 – 45.

Roethlisberger 1991, 78.

For the issue of Breenbergh’s replica drawings made after his return to the Netherlands, see Alsteens 2015.

Roethlisberger admitted this (1991, 78), though it is true that he occasionally spelled his name Breenborch in the years 1626 – 29, as a survey of his signed drawings makes clear.

F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, no. 3. The drawing was previously published with the date of 1657 in Stockholm 1953, no. 160; and in the 1974 auction (see Provenance).

Besides the Amsterdam and Boston drawings illustrated in this entry, a sheet in Düsseldorf can be added to this 1627 group; see Roethlisberger 1969, no. 101; and Düsseldorf 1968, no. 20.

These fully signed and dated drawings from 1627 can be found in the Albertina, Vienna (Roethlisberger 1969, no. 99; and New York & Fort Worth 1995, no. 78); the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (Jansen & Luijten 1988, no. 45; and London & Antwerp 1999, no. 46); and two in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (Roethlisberger 1969, no. 107; and Schapelhouman & Schatborn 1998, nos. 76, 77). The orthography of the signatures is also similar.

See, for example, the date on the drawing in Berlin; Roethlisberger 1969, no. 20.

Roethlisberger 1969, no. 166; and Darmstadt 1992, no. 75.

For this drawing, see the dealer catalogue by Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker, London & New York 2018, no. 34.

Idem.

For this partial sheet, see Chicago 2019 – 20, 244 – 45, 291 (no. 90). Carlos van Hasselt thought it certainly by Breenbergh (Brussels, Rotterdam, Paris & Bern, under no. 26); and Roethlisberger probably so (1969, under no. 104). Whether or not the Chicago drawing was itself ever cut down is also a question worth posing.