Choose a background colour

Jacques de Gheyn II, Dutch, 1565-1629

:

Sorceress with a Quill Pen, c. 1610-20

Pen and brush in brown ink with additions in red chalk on paper

3 5⁄16 × 5 7⁄8 in. (8.4 × 14.9 cm)

Recto, lower right, monogrammed by the artist and numbered (also by the artist?) in black ink, IDG in ligature, 16; verso, lower center, in pencil, Massa 1677 (fr. J. Auldjo’s Coll.), and below that, 258860, and 5 (circled).

- Chain Lines:

- Obscured by backing paper.

- Watermark:

- None

- Provenance:

John Auldjo, 1805 – 1886, London and Geneva (Lugt 48); Christian David Ginsburg, 1831 – 1914, London (Lugt 1145, stamp on verso of backing sheet); sale, Sotheby’s, Amsterdam, 21 November 1989, lot 6; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.35.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

None

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.35

Holding an extravagant quill pen, a bare-breasted woman looks down at an open book. She is likely a sorceress in the act of writing since Jacques de Gheyn II depicted witches like this in other works. For instance, the artist often imbued his subjects with an erotic appeal, depicted their spell books, or grimoires, and portrayed them as left-handed (which was a deviance according to contemporary thought). His emphasis on a seemingly dispassionate moment rather than the more spirited elements found in other works, however, may reflect the skepticism about witchcraft debated at that time within De Gheyn’s circle of scholarly friends. This atypical combination of motifs also demonstrates the artist’s talent for exploration and experimentation in his drawing practice.

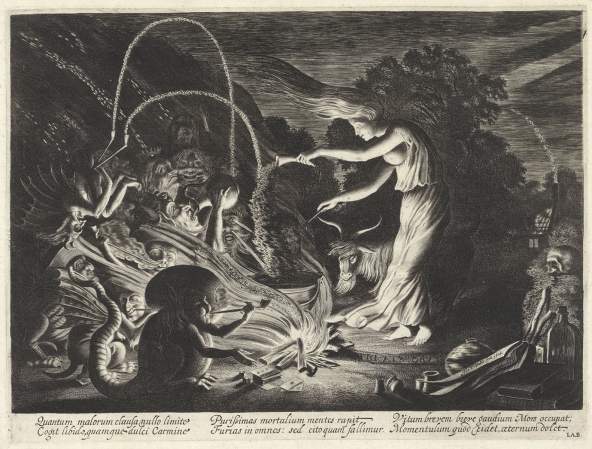

Jacques de Gheyn II clearly had an interest in witchcraft, which he conveyed in dozens of drawings, and in one major engraving, The Witches’ Sabbath Fig. 4.1.1

Andries Stock, after Jacques de Gheyn II, The Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbath. Engraving from two plates, 435 × 658 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-P1882-A-6180

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Without that body of work, it would be difficult to assess the status of this previously unpublished drawing of a barebreasted woman who holds a flamboyant quill pen in her left hand as she focuses on an open book. This iconography is highly unusual for the depiction of a sorceress. In fact, she accords well with the artistic conventions of bare-breasted courtesans found in Venetian Renaissance art among Titian and his followers and, in De Gheyn’s day, in the oeuvre of his own master Hendrick Goltzius (1558 – 1617).2

There are nevertheless compelling reasons to consider that the true subject of this drawing is a sorceress in the act of writing.

The woman’s left-handedness represents an important clue. One might assume that such a “deviance” (to the contemporary mind) would also be attributable to prostitutes, yet De Gheyn made a point of making many of his witches lefthanded. For example, in the abovementioned engraving of the Witches’ Sabbath, the seated witch uses her left hand to stir the pot, as does the one standing above her to gesticulate with her stick. Reversals of “handedness” were sometimes inherent to the mirror effect caused by the printing process. Claudia Swan convincingly argued, however, that De Gheyn intended this reversal, and that he deliberately employed the concept of inversion (meaning the natural world turned upside down or run backward) found in witchcraft imagery from previous generations.3

In some of De Gheyn’s other productions, such as his famous arms-training series called the Wapenhandelinge, he made sure that the soldiers appeared right-handed in print in order to conform with actual practice. De Gheyn likewise shows witches stirring or pointing with their left hands in a number of drawings, such as the Four Witches Cooking Parts of a Human Body in New York, and Two Witches Performing an Incantation in Oxford.4

While De Gheyn’s imagery can often be obscure and complex, in other instances where he features nude or partially nude women, they often correspond to conventional subjects, such as the prostitute-turned-saint Mary Magdalene, Pomona (with Vertumnus), or Helen of Troy (with Paris).5

Barring these identifications, a sorceress seems the most obvious solution in this case. Since there was already a long tradition of depicting old and haggard witches in tandem with young and voluptuous ones, De Gheyn appropriated the previous iconography of courtesans to add a certain erotic appeal. His younger colleague and occasional business partner, Jan van de Velde II (1593 – 1641), made use of a similar mode of representation for his masterpiece engraving, The Sorceress, from 1626 Fig. 4.2.6

Jan van de Velde II, The Sorceress, 1626. Engraving, 216 × 290 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-P-OB-15.310.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Depicting a witch occupied with writing may seem unusual, but spellbooks, or grimoires, appear in several of De Gheyn’s witchcraft images, particularly his large, finished Sabbath scenes that inherently feature the incantation of spells. One can find them in the Witches’ Sabbath drawings in Berlin and Stuttgart, and the two in Oxford.7

Unlike the books off to the side in Van de Velde’s engraving, De Gheyn almost always portrayed his witches actively engaged with their books. This aspect of sorcery is uncommon in previous witchcraft imagery by other artists and appears to have been a particular interest of De Gheyn’s. One of his most unusual drawings features a grimoire ceremoniously propped up on a skull lying on a cushioned pedestal, with studies of various contorted toads around it Fig. 4.3.8

Jacques de Gheyn II, Sheet of Studies of Attributes Used in Witchcraft. Pen and brown ink on paper, 94 × 353 mm. Paris, Fondation Custodia, inv. no. 6863.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

The book appears from two different vantage points, one of which reveals the contents of the open page: a hand in a circle, or “hand of glory,” used for invocation.9

This imagery can be found in copies of grimoires that survive from the seventeenth century, such as the popular Sleutel van Solomono (Key of Solomon).10

Due to their illicit nature, these books had to be copied by hand rather than printed, and surviving copies are only encountered in manuscript form.11

That De Gheyn depicted a sorceress writing or copying a grimoire appears to be the most likely explanation for the combination of elements in this drawing. It constitutes an unusual subject both in his oeuvre and within the larger body of witchcraft imagery of the era. This sorceress, in the quiet moment of her studious exercise, contrasts markedly with De Gheyn’s dramatic witches’ Sabbath imagery with its spells, creatures, and corpses. De Gheyn’s attitude toward witches and witchcraft is a large and complex subject in itself, but it should be noted that his artistic treatment comes at a time in which a revolution of thought took place, at least in the United Provinces. Many of the myths and superstitious lore around witchcraft were exposed as having no basis in reality, resulting in a transformation of the legal treatment of those accused of witchcraft.12

Much of this has been credited to the appearance of the 1609 Dutch translation of the Discoverie of Witchcraft by Reginald Scot, originally published in English in 1584, which offered the first thorough skeptical consideration of witchcraft practices. Work on this translation was carried out in Leiden by De Gheyn’s brother-in-law, Robert Brossard, along with his father, Thomas Bossard, who published it.13

The book was read and debated in the same university circles in which De Gheyn moved during his earlier residence in that city.14

Since De Gheyn crafted most of his witchcraft imagery around the same time, one can assume that he took an interest in understanding the current debates and skepticism, while at the same time taking advantage of the more obviously fantastical side of witchcraft for artistic exploration. De Gheyn often emphasized some of the most gruesome and far-fetched practices of witches in his art, making this noiseless and seemingly tranquil image of a literate and eroticized sorceress all the more notable for its contrast and its inherent originality.

End Notes

While the subject of De Gheyn’s witchcraft imagery is a large one, for key considerations, see especially in the concurrently appearing books Swan 2005, 123 – 94; and Hults 2005, 145 – 75. Other considerations include Judson 1973, 27 – 34; Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 1, 86 – 89; Löwensteyn 1986; Davidson 1987, 57 – 64; Löwensteyn 2011; and Zika 2016. For De Gheyn’s witchcraft subjects in his drawings, see Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 83 – 87, nos. 510 – 31. For the engraving, see New Hollstein (De Gheyn Family), vol. 1, 235, no. 155; and Swan 1999.

See, for example, Goltzius’s drawing of Mary Magdalene in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg; Reznicek 1961, vol. 1, 261, no. 78, vol. 2, pl. 418. For De Gheyn’s evident interest in Venetian Renaissance art, see the newly published drawing in Ackley 2015, 436 – 38, fig. 4.

The left-handedness in this print and the concept of inversion is the primary subject of Swan 1999.

For the drawing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, see Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 86, no. 524, vol. 3, pl. 342. For the drawing in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (not in Van Regteren Altena’s catalogue), see Löwensteyn 2011.

For these drawings, and his identifications of the figures, see Van Regteren Altena 1983, nos. 83, 84 (Mary Magdalene), no. 1050 (Pomona), and 493 (Helen of Troy). Less clear is the role, if any, of the similarly clad woman, in a sheet of studies in the Louvre; idem, no. 528.

Hollstein, vols. 33 – 34, no. 152

Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 85, no. 522, pl. 272 (Berlin); idem, vol. 2, 84 – 85, no. 519, pls. 337 – 39 (Stuttgart, preparatory for De Gheyn’s one engraving of the subject); idem, vol. 2, 86, no. 523, pl. 273 (Oxford); and Löwensteyn 2011 (Oxford, not in Van Regteren Altena 1983).

Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, 139, no. 892, vol. 3, pl. 386. For this drawing, see also Judson 1973, 28 – 29; Paris 1985, 46 – 48, no. 15, pl. 10; and Boon 1992, vol. 1, 160 – 62, no. 86, vol. 3, pl. 187.

Boon 1992, vol. 1, 161.

For grimoires in this period, see Davies 2009, 44 – 92.

Davidson 1987, 63 – 64.

For the historical situation, see especially De Blécourt & Gijswijt-Hofstra 1986; and Gijswijt-Hofstra & Frijhoff 1991; as well as further considerations in Swan 2005; and Hults 2005.

See Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 1, 86; and Löwensteyn 1986, 250 – 51.

Boon 1992, vol. 1, 162.