Choose a background colour

Nicolaes Maes, Dutch, 1634-1693

:

Sketch of St. Matthew and the Angel, c. 1652-53

Pen and brown ink on paper; framing lines in brown ink.

2 15⁄16 × 3 9⁄16 in. (7.5 × 9 cm)

Verso, upper right, in pencil, 23, 51, and encircled 3378; lower right, 10631, and center J.G.[?].

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 22 – 24 mm.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Probably George Ramsay, 1739, the 8th Earl of Dalhousie (once part of the family’s album of drawings by Rembrandt and his pupils, with many by Maes); by descent to Arthur George Maule Ramsay, 1878 – 1928, 14th Earl of Dalhousie, or John Gilbert Ramsay, 15th Earl of Dalhousie, Dalhousie Castle, Midlothian (Lugt 717a, mark on recto); dealer, P. & D. Colnaghi, London, 1922; dealer, Cassirer, Berlin, 1923 (who broke up the album and dispersed its contents); sale, Karl & Faber, Munich, 28 – 29 November 1990, lot 144; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.50.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Sumowski Drawings, vol. 8 (1984), 4130 – 31, no. 1842x; Robinson 1996, 318, no. 5.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.50

Nicolaes Maes trained with Rembrandt before returning to Dordrecht to become an independent master in 1653. This drawing shows Maes’s engagement with biblical subject matter before he turned exclusively to portraiture in the 1660s. It likely depicts an angel inspiring the evangelist Matthew at work on his gospel, a scene commonly illustrated by Rembrandt and his followers. With broad, energetic lines, Maes explores Matthew’s reaction to a presence that is heard, but perhaps not seen. Details such as the turning of Matthew’s head, his outward gaze, and his hand raised to his beard suggest a spiritual interaction. A study of a man, perhaps another biblical figure, is located on the reverse of the sheet.

After a period of training with Rembrandt in Amsterdam, Nicolaes Maes returned to his hometown of Dordrecht to set up as an independent master in 1653.1

He spent the remainder of the 1650s painting innovative scenes of domestic everyday life, for which he is best known today, along with a number of religious subjects. From the early 1660s onward, however, he abandoned these more creative-minded genres to devote himself entirely to portraiture, an activity that he carried out exclusively for the rest of his long and successful career. There are only around 110 surviving drawings that can be ascribed to Maes with confidence, almost all of which appear to date to the 1650s, and thus from his earliest and most inventive phase.2

The Peck drawing was once part of the Dalhousie album, a bound group of eighty-four sheets by Rembrandt and his followers that remained with the Scottish Earls of Dalhousie for almost two centuries before being sold and dispersed in the 1920s.3

The earls’ distinctive mark of the letter D with a crown, seen here in the lower left corner, can still be found on many of the sheets. Wilhelm Valentiner quickly recognized that a number of the drawings in the Dalhousie album must be by Maes, since several clearly served as compositional studies for some of his works from the 1650s, such as his well-known “eavesdropper” paintings.4

William Robinson convincingly established that at least thirty-four of the drawings from the Dalhousie album are by Maes, including the present work.5

Other artists represented in the album were likewise some of Rembrandt’s most famous pupils, including Ferdinand Bol (1616 – 1680), Govert Flinck (1615 – 1660), Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627 – 1678), Willem Drost (1633 – 1659), and Philips Koninck (1619 – 1688).6

Werner Sumowski, who first published this drawing, identified the subject as Elijah and the Angel.7

In this Old Testament episode, the despairing prophet Elijah is awoken in the wilderness by an angel who provides him with food and drink (1 Kings 19:5 – 7). It was a subject occasionally treated by Rembrandt and his pupils, and also Maes in a drawing in Frankfurt Fig. 40.1.8

Nicolaes Maes, Elijah and the Angel. Pen and brown ink with bluish and reddish washes on paper, 181 × 148 mm. Frankfurt, Städel Museum, inv. no. 13055.

Bildagentur/Städel Museum/Frankfurt am Main/Art Resource, NY

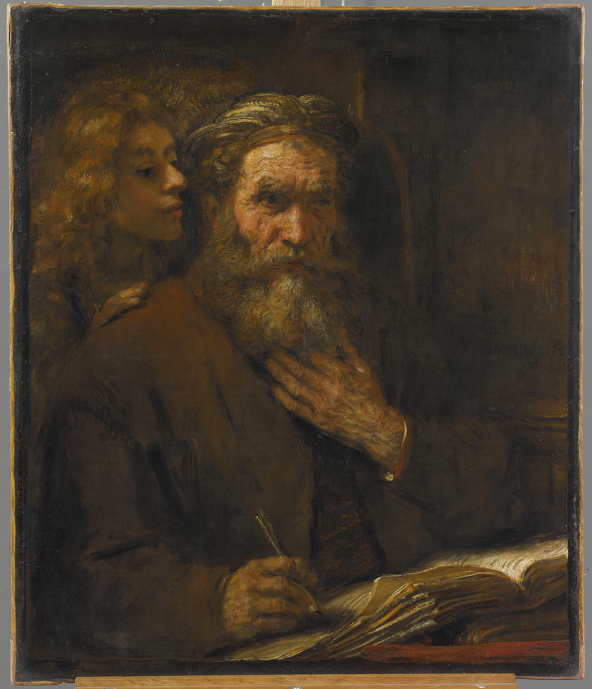

The Peck drawing, however, does not fit the iconography of such a scene very well, lacking signs of a wilderness setting, Elijah having been asleep, or food and drink. Far more likely is that the sketch depicts St. Matthew and the Angel, showing the evangelist at work on his Gospel while receiving inspiration from an angel. This was also a popular subject among Rembrandt’s followers, and Rembrandt painted his own celebrated version of the subject in 1661 showing the angel gently whispering inspiration into the ear of the writing saint, who strokes his beard Fig. 40.2.9

Rembrandt, St. Matthew and the Angel, 1661. Oil on canvas, 96 × 81 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. no. 1738.

RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

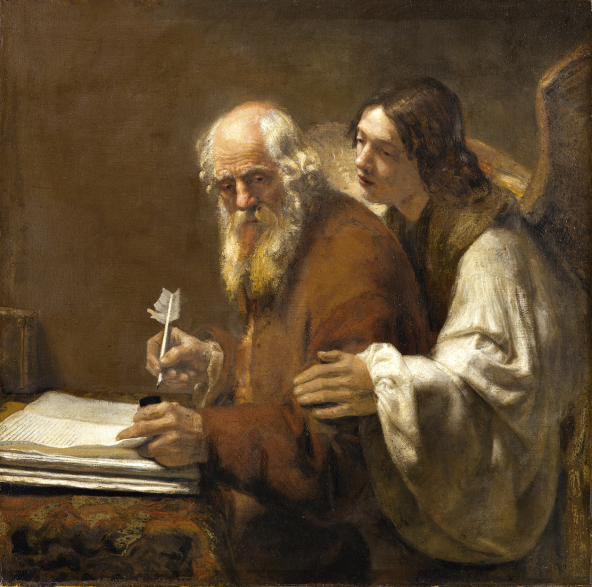

An even more compelling comparison with Maes’s sketch can be found in a painting currently attributed to Karel van der Pluym (1625 – 1672) in the North Carolina Museum of Art that shows Matthew turning his head slightly in the direction of the angel, whose presence is heard and felt but perhaps not seenFig. 40.3.10

Attributed to Karel van der Pluym, St. Matthew and the Angel, c. 1655 – 60. Oil on canvas, 106.6 × 108 cm. Raleigh, North Carolina Museum of Art, inv. no. 59.35.1.

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina and Public Subscription, in memory of W. R. Valentiner

Working out the ethereal nature of the interaction may have been Maes’s primary concern in the Peck drawing, capturing the nature of divine manifestation and presence.

Many paintings by Rembrandt and his followers depicting evangelists and apostles seem to have been produced as stand-alone works (rather than made and sold in series).11

Maes painted individual apostles on at least two occasions, though neither depicts St. Matthew.12

One is his St. Thomas in Kassel.13

The other is a similarly scaled St. Andrew that emerged on the art market in 2011.14

Although doubts about Maes’s authorship of these two works have been expressed in the past, Ariane van Suchtelen recently accepted both without reservation in the major 2019 – 20 exhibition devoted to Maes.15

Despite the fact that the Peck drawing cannot be connected to any known painting, it might be a compositional sketch or primo pensiero for a painting that never came to fruition, or has subsequently been lost. He could have also just drawn it for exercise, as was likely the case for a number of his other loose sketches unconnected to paintings. Sumowski surmised that the Peck drawing might have been made around 1652 – 53, but a slightly later date should also be considered given that the St. Thomas in Kassel is dated 1656, and that the evangelist and apostle theme only seems to have become popular among Rembrandt and his followers beginning in the late 1650s.

The sketch on the verso, unknown to Sumowski, is published here for the first time. It shows an old man holding one arm to his chest and reaching out with the other one for support. It is possibly a study for the figure of Jacob, who reacts with profound grief when he is shown the bloodstained cloak of Joseph, and believes his son to be dead (Genesis 37:31 – 34). The intense drama of this moment frequently served as subject matter for Rembrandt and his followers, including Maes. His drawing of the subject in the Metropolitan Museum of Art depicts a similarly bearded Jacob who also holds his hand to his chest Fig. 40.4.16

Nicolaes Maes, Jacob Receiving Joseph’s Blood-Stained Cloak, c. 1653. Pen and brush in brown ink over red and traces of black chalk on paper, 220 × 302 mm. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 2005.418.12.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous Gift, 2005

End Notes

For Maes’s life and works, see especially The Hague & London 2019 – 20; Krempel 2000; and Robinson 1996.

For Maes’s drawings, see Sumowski Drawings, vol. 8 (1984); Robinson 1989; Robinson 1996, 96 – 149; and M. Schapelhouman in The Hague & London 2019 – 20, 183 – 97. Defining Maes’s drawn oeuvre remains problematic. Sumowski catalogued 265 drawings by Maes, but Robinson argued that around 100 of his attributions are worthy of rejection on stylistic grounds, and that a further fifty-seven works, those that fall into the so-called Pseudo-Victors group, should also be removed from his oeuvre; see Robinson 1996, 97 – 99. For a recent reconsideration of the Pseudo-Victors group, named for its early but rejected attribution to Jan Victors (1619 – 1676/77) and later considered the work of Maes’s stepson, Justus de Gelder (1650 – 1707), see M. Schapelhouman in The Hague & London 2019 – 20, 188 – 91, who argues that this group is indeed the work of a very young Maes.

For the Dalhousie album in general and a reconstruction of its contents, see Robinson 1996, 315 – 27. For the Earls of Dalhousie, see Lloyd Williams 1992, 163; and the entries under Lugt 717a (www.marquesdecollections.fr). The family actually possessed two albums of drawings: the one under discussion, and another containing Italian drawings dispersed at the same time. The albums appear to have been already formed before they were acquired, probably by George Ramsay (1739 – 1787), the 8th Earl of Dalhousie, but their earlier provenance remains a mystery.

Robinson 1996, 318 – 21, nos. 1 – 34; and for the Peck drawing, idem, 318, no. 5. Several of Maes’s drawings formerly in the Dalhousie album are now in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; see Giltaij 1988, 222 – 34, nos. 112 – 13, 115 – 21. Many of the rest remain in private hands.

For the drawings attributed to other artists formerly in the Dalhousie album, see Robinson 1996, 324 – 26, nos. 56 – 74.

Rembrandt Corpus, vol. 6, no. 289. See also A. Blankert in Melbourne & Canberra 1997 – 98, 161 – 63, no. 22; and A. K. Wheelock in Washington & Los Angeles 2005, 92 – 98, 134, no. 7.

Weller 2009, 162 – 64, no. 35.

These “portraits” of evangelists and apostles were the subject of Washington & Los Angeles 2005. Note that Matthew (along with John) is one of the four evangelists who also counts among the twelve apostles.

A. van Suchtelen in The Hague & London 2019 – 20, 28 – 29, figs. 8 – 9.

Nicolaes Maes, St. Thomas, 1656, oil on canvas, 120 × 90.3 cm (Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv. no. GK 246). See Schnackenburg 1996, vol. 1, 176; and A. van Suchtelen in The Hague & London 2019 – 20, 46 – 49, no. 4.

Nicolaes Maes, St. Andrew, c. 1656, oil on canvas, 107.1 × 84.5 cm (sale, Sotheby’s, London, 7 – 8 December 2011, lot 207, as “attributed to Maes”).

The Hague & London 2019 – 2020, 46 – 49, no. 4, and 205, note 14.

For another drawing by Maes of Jacob Shown the Blood-Stained Cloak of Joseph with a similar bearded figure, see the sheet in Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland, inv. no. D2865; Andrews 1985, vol. 1, 49, no. D2865, vol. 2, 79, fig. 327.