Choose a background colour

Godfried Schalcken, Dutch, 1643-1706

:

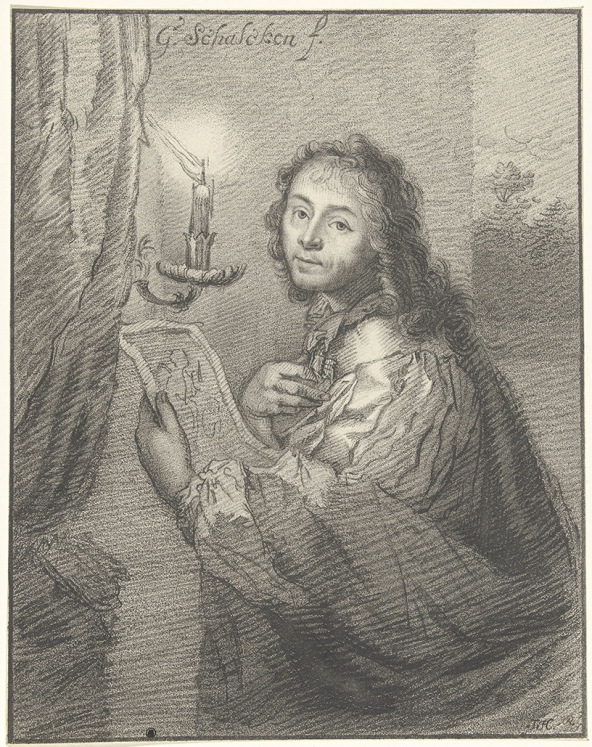

Self-portrait (Study for the Uffizi Painting), c. 1694-95

Black chalk on paper.

8 9⁄16 × 6 11⁄16 in. (21.8 × 17 cm)

Verso, lower left in pencil, £7 Fr. Mieris.

- Chain Lines:

- Vertical, 17 – 18 mm.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Probably Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, 1642 – 1723, Florence; Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri, 1676 – 1742, Florence (Lugt 2992b), his inv. fol. 52v (Gofredo Schalcken Fiammingo, a lapis nero in / Quadro, per alto p. 7½ largo p. 6 con gli stessi / ornate come sopra); dealer, Willem Kent, 1685 – 1748, London; Charles Rogers, 1711 – 1784, London (Lugt 624, mark on recto); his sale, Thomas Philipe, London, 22 April 1799, lot 608 (SCHALCKEN (Sir Godfrey). His portrait, by himself — black chalk — designed for the picture in the Florentine Gallery); John Thane, 1748 – 1818, London (Lugt 1544, mark on recto); Christiaan Josi, 1765 – 1828, Amsterdam and London (Lugt 573); Lord Northwick; his sale, Sotheby’s, London, 5 July 1921, lot 85; Henry Scipio Reitlinger, 1882 – 1950, London (Lugt 2274a); his sale, Sotheby’s, London, 22 June 1954, lot 707; sale, Sotheby’s, Monaco, 22 February 1986, lot 25; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.79.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Josi 1821, vol. 1, 53, vol. 2, pl. 41; Reitlinger 1923, 157, pl. 48 (as Frans van Mieris the Elder); Naumann 1978, 33; Raupp 1984, 217 – 18, pl. 121; Beherman 1988, 34, 153 (fig. 56b, incorrectly identified as fig. 56a), and 374, no. D – 1; Chiarini 1989, 522; Langedijk 1992, 165, and 167, fig. 39a; N. Turner 1993, 210, App. III, no. 52; J. S. Turner 2015, 493, no. 34, and 495, note 13. Franits 2018, 98 – 99, fig. 49, and 159, no. A3D1.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.79

Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici had a famous gallery of artists’ self-portraits, a portion of which is still hanging today in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. In an act of self-promotion, Godefridus Schalcken suggested his own inclusion in the gallery with a nighttime scene, his particular specialty. This highly finished self-portrait, therefore, likely functioned as a vidimus, a drawing artists showed to a patron for approval before beginning a project. It portrays the artist illuminated by candlelight and gazing directly at the viewer, his right hand in a self-reflective pose. In his left hand he holds a print made after his now lost painting of Mary Magdalene. Schalcken included an impression of the print with the finished painting likely to please his patron, an avid print collector.

This drawing can be dated narrowly to the years 1694 – 95 since it relates directly to Godefridus Schalcken’s painted self-portrait commissioned by Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici (1642 – 1723) for his gallery of artists’ self-portraits Fig. 67.1.1

Godefridus Schalcken, Self-Portrait, 1695. Oil on canvas, 92.3 × 81 cm. Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv. no. 1878.

Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi

This famous collection, a portion of which is still hanging in the Uffizi today, was begun by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici (1614 – 1675) around 1664.2

His nephew Cosimo contributed to the collection early in the project, and took charge of it after Leopoldo’s death, devoting considerable time and expense to expanding the gallery to include as many notable painters of the past and present as possible. The collection also included a number of Dutch artists. Cosimo toured the Netherlands himself on two occasions, in 1667 – 68 and again in 1669, during which he visited the studios of many painters, most notably Rembrandt’s (1606 – 1669). By the time of the Schalcken commission, Cosimo had already obtained self-portraits by Rembrandt, Gerrit Dou (1613 – 1675) (Schalcken’s teacher), and Frans van Mieris (1635 – 1681).3

A number of letters related to the Schalcken commission survive, which pinpoint the date and reveal that it was the artist who first suggested, through his agent, that he might contribute a painting to the grand duke’s gallery.4

This took place during Schalcken’s London period in 1692 – 96, when his fame reached new heights with a broader and wealthier clientele than that in the Netherlands at the time.5

This written correspondence took place between Schalcken’s agent in London, Thomas Platt (who had spent time in Italy and was familiar with Cosimo’s collection), and the grand duke’s secretary, Apollonio Bassetti. One of the main points of discussion was how the artist would present himself. Schalcken proposed a nighttime setting since this was his foremost specialty, and because the gallery of self-portraits as yet contained no others set at night. Schalcken was particularly celebrated for his candlelight scenes, then as now, and he painted at least two other candlelit self-portraits during his period in London.6

In another of these he wears the same archaic slashed doublet seen here. Such contrived clothing seems to relate to Schalcken’s presentation of himself in an elegant Van Dyckian pose, developed in a previous age, with his head engaging the viewer from over his shoulder and his hand gesturing gracefully to himself.7

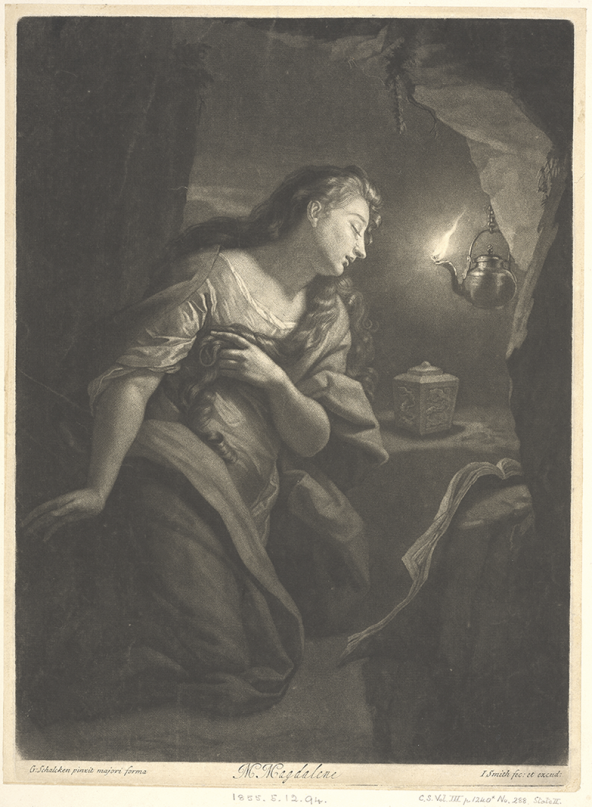

The sheet of paper Schalcken holds is a mezzotint by John Smith (1652/54 – 1742) after a now lost painting by Schalcken depicting Mary Magdalene by candlelight Fig. 67.2.8

John Smith, after Godefridus Schalcken, Mary Magdalene by Candlelight, 1693. Mezzotint, 348 × 252 mm. London, British Museum, inv. no. 1855,0512.94.

The Trustees of the British Museum

Her image is obscured in the painting in the Uffizi, but the general form of her figure can just be made out in the drawing. The precise identification of the print is made clear in the letters related to the commission.9

Schalcken included an impression of the mezzotint with the finished painting that he sent to the grand duke. Cosimo then gave that impression to his secretary Bassetti, but requested that another be sent, this time (in order for it not to become creased, apparently a problem with the first one) rolled around a piece of wood and sent in a tube.10

Smith’s mezzotint today ranks as one of the best he made. Schalcken commissioned it from him shortly after he arrived in London, a fact we know from Smith’s own notes (in an album preserved in the New York Public Library) that he carried out the work in 1693.11

Why Schalcken chose to depict himself holding a print rather than one of his original paintings remains something of a mystery, but it may be that he planned from the outset to send Cosimo an impression of it, knowing that he was an avid print collector. The subject of Mary Magdalene, in any case, would have certainly appealed to his patron’s devout Catholic sensibility.12

This drawing has long been assumed to be a preparatory study for the painting, which might indeed be the case, but its highly finished nature also suggests other possibilities in terms of function. Schalcken’s drawn oeuvre is quite small, numbering fewer than forty sheets today, many of these representing similarly highly finished portrait drawings that relate closely to paintings.13

A number of scholars, beginning with Guido Jansen, have suggested that some of these might actually be ricordi, or drawings made after the painting was completed in order for the artist to keep a record of the work once it left the studio.14

Supporting this notion are a few other drawings by Schalcken that are sketchier in nature and appear to have been true preparatory studies. A third, and more likely possibility, however, is that rather than being a preparatory study or ricordo, this drawing served as a vidimus, a drawing shown to the patron for his or her approval before the painting was executed. The letters between Platt and Bassetti do not specifically mention a vidimus, but enough of their discussion pertains to the nature of the agreed composition that sending such a drawing during negotiations would not be a surprise, nor would one expect it to be specifically referenced in the letters. The strong centerfold seen in this drawing appears to be quite old and might be the result of having been sent with the letters.

A fascinating recent discovery about the early provenance of the drawing reinforces the theory that it was sent directly to Cosimo or his agent as part of the commission. In 2015, Jane Shoaf Turner published the earliest specific mention of this drawing in the pre-1741 inventory of Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri (1676 – 1742), a Florentine collector and diplomat in the service of the grand duke.15

Gabburri collected portrait drawings of artists, perhaps to have engraved as part of his unpublished four-volume “Lives of the Painters” (Vite de’ pittori). Cosimo may have gifted or sold this drawing to Gabburri, much as he gave Smith’s mezzotint to his secretary Bassetti. Also possible is that Schalcken simply included the drawing with the finished painting to provide an example of his draftsmanship as an extra gift. Whatever the case, the early provenance in an Italian collection belonging to a close associate of Cosimo strongly implies that it once belonged to the grand duke himself.

Some follow-up letters from 1700 mention a sketch (schizzo) of the painting, made at the request of Schalcken, who had sudden fears that some nefarious soul had substituted a painted copy of a different self-portrait during the transit to Italy a few years earlier.16

He requested that a sketch be made and sent to confirm the present pose, which was indeed sent and greatly relieved him. In his catalogue of Schalcken’s oeuvre, Thierry Beherman rightly accepted the Peck drawing as an autograph self-portrait, but expressed some hesitation due to the possibility that it might be the sketch referred to in the later letters.17

His doubts, however, are unfounded. The style of the drawing reveals Schalcken’s distinctive virtuosic handling in certain passages, such as the face and reflected light on his shoulder and sleeve, as well as his characteristic use of diagonal hatching throughout the composition. This is obviously a finished drawing (disegno), rather than sketch (schizzo) made merely for the purpose of confirming the composition for the panicked artist back in the Netherlands. Interestingly, the physiognomy of the face in the Peck drawing does not closely match Schalcken’s, who also would have been in his fifties at the time, rather older than the countenance seems here. This might be due to his use of a studio assistant for the pose, just as he did for the only other known self-portrait drawing by the artist, as Wayne Franits pointed out.18

In 1821, the Peck drawing had the distinction of being included in the Collection d’imitation de dessins by Christiaan Josi (1768 – 1828), one of the first publications to reproduce a selection of European drawings in print 67.3.19

Christiaan Josi, after Godefridus Schalcken, Self-Portrait of Godefridus Schalcken, before 1821. Mixed intaglio techniques (“print-drawing”), 229 × 182 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-P-ON-47.810.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The plate’s extremely high degree of fidelity to the form and texture of the drawing is the result of a notable process developed by the printmaker Cornelis Ploos van Amstel (1726 – 1798) to make “print drawings” (prenttekeningen).20

The majority of the plates in Josi’s publication were made by Ploos van Amstel (Josi’s teacher), and it has long been assumed in previous literature that this Schalcken self-portrait prenttekening was the work of Ploos van Amstel as well. As Josi makes clear in the text volume, however, this was one of a handful of plates he made himself using the technique he learned from his mentor.21

Josi also proudly disclosed that he owned the original drawing, stating the price he paid (10 louis), and noted that the artist’s drawings were already rare and highly sought-after.22

Thus, within about the first century of its existence, the Peck drawing had traveled from London where it was made, to Italy, back to London (where Gabburri’s collection was largely sold), and then to Schalcken’s home country of the Netherlands, where it was reproduced in a book celebrating great drawings. Despite its early fame and long publication history, however, this exhibition actually marks the first known occasion that this drawing has been publicly shown

End Notes

Beherman 1988, 153 – 54, no. 56; and Langedijk 1992, 165 – 71, no. 31. For the most informative discussions of this painting and the commission, see Cook 2016, 185 – 91; Franits 2016, 21 – 28; and Franits 2018, 77 – 87.

For the gallery of self-portraits in the Uffizi, see Giusti & Sframeli 2007.

See Franits 2016, 21 and 37 (note 5) with further references regarding Cosimo’s travels in the Netherlands. The Dutch self-portraits in the collection are catalogued in Langedijk 1992.

Langedijk 1992, 168 – 71, under no. 31. The letters are preserved in the Archivio di Stato, Florence.

For Schalcken’s London period, see especially Franits 2018. For Dutch artists in London at the time, and their motivations and clientele, see Karst 2013 – 14.

For these other London self-portraits, see Franits 2016; and Franits 2018, 77 – 105.

See Raupp 1984, 217 – 18; Cook 2016, 190; and Franits 2018, 84 – 86.

For Smith’s mezzotint, see Beherman 1988, 105 – 06, no. 22; Griffiths 1998, 243, no. 168; and W. Franits in Cologne & Dordrecht 2014 – 15, 289 – 91, no. 78.

Langedijk 1992, 170, letters XI – XII.

Beherman 1988, 416.

Griffiths 1989, 256.

For Schalcken’s drawn oeuvre, see Beherman 1988, cataloguing thirty-four works as by Schalcken. Jansen 1992 adds four drawings to this group, while questioning two of the works Beherman accepted.

Jansen 1992, 80. See also Stefes 2011, vol. 1, 503 – 04, no. 939; and Anja Sevcik in Cologne & Dordrecht 2015 – 16, 58 – 59.

Turner 2015, 493, no. 34. See in the provenance above for a transcription of the entry in Gabburri’s inventory of drawings, now in the Fondation Custodia, Paris. The likely presence of this work in Gabburri’s collection was pointed out earlier by Nicolas Turner, who noted that many of Gabburri’s drawings ended up with Charles Rogers in London, as here; Turner 1993, 210, Appendix III, no. 52. For Gabburri’s portrait drawings generally, see Donati 2014, which neglects to mention the present work by Schalcken (as pointed out in Turner 2015, 495, note 13).

See the transcriptions in Langedijk 1992, 170 – 71, letters XIII – XV.

Beherman 1988, 34.

Franits 2018, 97 – 100. Franits further speculated that the model might be the artist’s nephew, Jacobus Schalcken (born c. 1681 – 82), who was said to have studied with him.

Josi 1821, vol. 2, pl. 41. For a study of Josi’s publication, see De Luise 1995. For this particular plate, see Laurentius, Niemeijer & Ploos van Amstel 1980, 289, no. 82. The only major difference with the original drawing is the addition of the artist’s signature prominently across the top of the print.

Laurentius, Niemeijer & Ploos van Amstel 1980, 112 – 31, 322 – 25.

Josi 1821, vol. 1, 53 (“Celui dont l’imitation, faite par moi-même…”). For the difficulty in distinguishing some of the other additions by Josi from those of Ploos, see De Luise 1995, 224.

Josi 1821, vol. 1, 53. Beherman wondered if Josi’s plate reproduced a second version of the drawing (see Beherman 1988, 374, no. D1) since the two collectors’ marks reproduced on the recto of the print, found also on the drawing, are slightly different; however this has only to do with the fact that Josi read (mistakenly) the marks as those of the famous British collectors Thomas Hudson and Jonathan Richardson, as he states in his text volume (Josi 1821, vol. 1, 53), and slightly transformed the marks of John Thane and Charles Rogers to read more as a TH and R rather than JTh and CR to reflect his supposition.