Choose a background colour

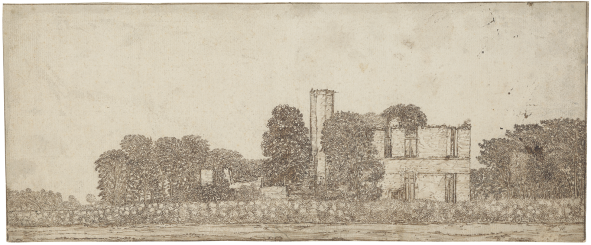

Hendrik Hondius I, Dutch, 1573-1650: Ruins of Castle Spangen, c. 1605

Pen and brown ink with brown wash over black chalk on paper; framing lines partially visible in black chalk.

8 13⁄16 × 13 1⁄8 in. (22.4 × 33.4 cm)

Verso, lower right, in pencil, Large bon 2.

- Chain Lines:

- Horizontal, 17 – 19 mm.

- Watermark:

- Cluster of Grapes. Similar to Briquet, no. 13217; and Schapelhouman and Schatborn 1998, no. W121 (cat. 445, anonymous artist, early seventeenth century). Backing sheet with Strasbourg Lily, probably eighteenth or early nineteenth century. See Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 130, no. R16.

- Provenance:

Hubert Dupond, 1901 – 1981⁄82, Brussels (Lugt 3926, stamp on recto); sale, Christie’s, Amsterdam, 18 November 1985, lot 57; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.45.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

Orenstein 1992, 498, no. 1; F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999 – 2001, 64 – 65, no. 16; S. Kuretsky in Poughkeepsie, Sarasota & Louisville 2005 – 06, 123 – 24, no. 6.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.45

During a period of ceasefire between the Dutch and Spanish amid the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648), Dutch artists developed an interest in local architectural ruins. Ravaged buildings were both a glaring reminder of the devastation of battle and a source of new aesthetic potential. Built in 1325, the fortified medieval château known as Spangen Castle was burned down by the Spanish in 1574 and eventually razed in the nineteenth century.

Faintly visible black chalk guidelines suggest Hendrick Hondius drew the site from life. His precise line work and light touch, particularly in the soft reflections of the castle in the water, convey a sense of stasis in time, a striking counterpoint to the life that carries on in the farmhouses beyond.

Spending most of his career in The Hague, Hendrik Hondius became one of the leading print publishers in the Netherlands in the first half of the seventeenth century.1

A significant printmaker in his own right, his prints far outnumber his relatively rare drawings, which nevertheless confirm him as an accomplished draftsman.2

Among his distinctions was to serve as the drawing master for the young Constantijn Huygens I (1596 – 1687), an experience described in the latter’s autobiography.3

Hondius’s light, yet precise touch is apparent in the present work. The prominent watery reflection of the castle in the lower half of the sheet contrasts subtly with the delicate precision of the architectural rendering above, and lends the scene a sense of unperturbed calm. The sheet depicts the ruins of the Castle Spangen, a fortified medieval château that once stood near Overschie, a village in Hondius’s day but now an urban neighborhood in the western part of Rotterdam.4

Philips van Mathenesse built the structure on earlier foundations in 1325 (not in 1310 as frequently given), dubbing it Spangen, which he adopted as the family name.5

Like many late medieval castles in Holland, it endured multiple destructions and underwent various phases of rebuilding during the Hook and Cod Wars in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.6

Also like many Dutch castles, it met its ultimate demise during the early phases of the Eighty Years’ War (1568 – 1648). A band of looters from Delft destroyed much of it in 1572, with a final burning by the Spanish army in 1574. This was a period when troops under the Duke of Alva (1507 – 1582) overran a great deal of territory in the heart of the province of Holland, and castles and other fortified structures were destroyed by both Spanish and Dutch troops to prevent either from using them. Most were never rebuilt. The remaining ruins of Spangen are no longer visible, having been torn down sometime in the nineteenth century.

Seventeenth-century Dutch artists took a great interest in depicting these local ruins, a practice that began in earnest during the period of the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609 – 1621) when the visible history of the newly independent republic engaged humanists and artists alike.7

Another early depiction of Spangen comes from the hand of Willem Buytewech (1591/92 – 1624), whose distinctive drawing of the structure probably dates to some point shortly after his return to his hometown of Rotterdam in 1617 Fig. 6.1.8

Willem Buytewech, Ruins of Spangen Castle, c. 1617 – 18. Pen and brown ink on paper, 144 × 350 mm. Paris, Collection Frits Lugt, Fondation Custodia, inv. no. 2356.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

The overgrowth and trees around the ruin appear even further developed in a drawing by Roelant Roghman (1627 – 1692) made three decades later around 1646 – 47 during his major project of depicting castles around the country Fig. 6.2.9

Roelant Roghman, Ruins of Spangen Castle, c. 1646 – 47. Black chalk and gray wash on paper, 324 × 488 mm. Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv. no. O++ 047.

Teylers Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands

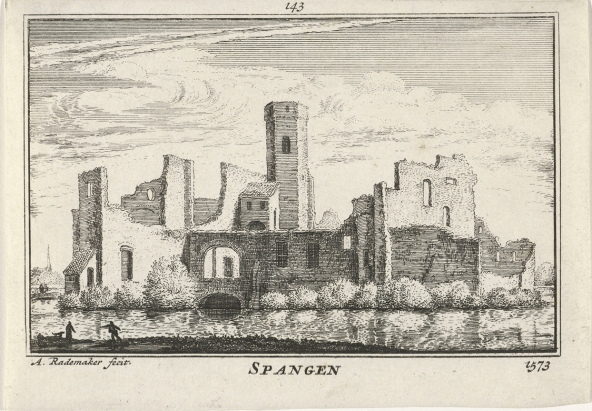

Essential, however, for the identification of these ruins is Abraham Rademaker’s 1725 publication featuring views of many Dutch castles and older structures, which includes six views of Spangen from several different angles Fig. 6.3.10

Abraham Rademaker, Ruins of Spangen Castle in 1573, c. 1725. Etching on paper, 80 × 115 mm. Book illustration for Kabinet van nederlandscher outheden en gezichten, plate 143. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-P-OB-73.496.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rademaker based his views of the castle on images that are no longer extant and remain a mystery in terms of their source and authorship. He provided one “before” image of the still intact castle that he dated to 1550 and five post-destruction images dated 1573. The latter set thus comes just after its initial destruction by Delft bandits in 1572, but before its final burning by Spanish troops in 1574. This probably accounts for the differences in the appearance of the ruin found in the later drawings by Hondius, Buytewech, and Roghman. The distinctive central stair tower remains visible in all but Roghman’s obscured view.

Hondius’s career overlapped the dates of production of Buytewech’s and Roghman’s images, and his style remained remarkably consistent over the course of his career, making the dating of his drawings on stylistic grounds a difficult exercise. If the present sheet is the earliest of the three, which seems likely, then it would probably be the earliest extant image of the castle (given the loss of Rademaker’s sources). A previously suggested date of circa 1640 – 50 for the Peck drawing proves problematic when considering the apparent topographic differences in overgrowth and reduced moat size found in the other drawings.11

The watermark in this sheet also suggests an earlier date. This would be more in keeping with Hondius’s related drawing of Tervueren Castle outside of Brussels, similar in style and composition, that he signed and dated 1605 Fig. 6.4.12

Hendrik Hondius, The Château of Tervueren, 1605. Pen and brown ink, watercolor in blue, gray-green, and pink, over traces of black chalk on paper, 147 × 223 mm. New York, Morgan Museum & Library, inv. no. 1978.40.

The Morgan Library & Museum. 1978.40. Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Christian H. Aall

Both this drawing and Hondius’s view of Tervueren position the moated castles on the sheet in a manner that affords a nearly full consideration of the reflected structure in the water. An important distinction with the present sheet, however, is that Hondius appears to have drawn the ruins of Spangen from life, evidence of which can be seen in the numerous black chalk guidelines that he searchingly redrew to generate a more precise outline of the structure. His drawing of Tervueren, on the other hand, is one of several closely related drawings by various draftsmen, suggesting a drawn prototype that was copied by multiple artists rather than one made on-site.13

That Hondius should both craft original works by drawing on-site as well as make copies after other artists’ works does not come as a surprise, since we find evidence of both in his other drawings.14

The castle of Tervueren was located at a greater distance away (in the Southern Netherlands, then under Spanish control) than Spangen, which Hondius could have easily reached within half a day’s walk from his home in The Hague. Although Hondius was Flemish and may have traveled back to his land of origin one or more times, it seems more likely that he copied subject matter set far away rather than close to home.

Unlike his many drawings that were used to make prints, the ultimate purpose of the present sheet is unclear. Given the similarity of his drawings of Tervueren and Spangen, one might be tempted to posit a planned series of prints of castles that never came to fruition. There is no evidence, however, to support such a notion. These two drawings differ considerably in size as well as coloring, and furthermore, Tervueren was then a functioning castle (one of the main residences of the Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella) rather than a ruin. He did use the bottom portion of Tervueren for a print of an imaginary castle he designed and engraved in 1612, showing that this sort of drawing could prove useful as a general architectural study.15

His drawing of Spangen, by contrast, may have been driven by a powerful new sensibility that took hold in Dutch art at the time. The destruction of the once-stately ancestral homes of the local nobility served as a reminder of the ravages of war and time, and the image and concept of a ruin, as opposed to an intact structure, began to find greater artistic and aesthetic potential in the Netherlands.

End Notes

See Orenstein 1996 for the fundamental study of Hondius and his career as a print publisher.

Orenstein catalogued thirty-two drawings in her unpublished dissertation; see Orenstein 1992, 488 – 99. For the catalogue of prints, see the New Hollstein (Hondius) volume by the same author

Huygens 1987, 69 – 73.

The subject of the drawing was first identified by C. J. van der Klooster in advance of its sale at Christie’s, Amsterdam, 18 November 1985, lot 57.

See Renaud 1943 for the early history of the castle, correcting earlier errors still encountered in the literature. The same author also published a number of articles related more specifically to his archaeological excavations in and around the castle in the 1940s and early 1950s.

For the ruin as artistic subject during the Twelve Years’ Truce, see, with further references, Fucci 2021; Fucci 2018a; and the essays by S. Kuretsky and C. Levesque in Poughkeepsie, Sarasota & Louisville 2005 – 06, 17 – 48, 49 – 62.

Haverkamp-Begemann 1959, 140 – 41, no. 110, fig. 89; Rotterdam & Paris 1974 – 75, 79 – 80, no. 102, pl. 111 (identified as the ruins of Spangen for the first time); and New York & Paris 1977 – 78, 37 – 38, no. 23, pl. 31 (crediting Jeroen Giltaij with the initial identification).

Van der Wyck & Kloek 1989 – 90, vol. 1, 196, no. 177, vol. 2, 116 – 17, fig. 175; and Plomp 1997, 340, no. 386.

Rademaker 1725 (facsimile reprint, 1975), nos. 139 – 44, unpaginated. For Rademaker’s project generally, see Beelaerts van Blokland & Dumas 2006; and for his views of Spangen, idem, 196 – 97, 407 – 08.

For the later date, see F. Robinson in Chapel Hill, Ithaca & Worcester 1999– 2001, 64 – 65, no. 16.

Stampfle 1991, 46 – 48, no. 77; and Paris, Antwerp, London & New York 1979 – 80, 36 – 38, no. 6.

For a discussion of this group of related drawings of Tervueren, see especially Haverkamp-Begemann et al. 1999, 148– 52, no. 35 (centered on a version by an unidentified Flemish artist in the Lehman Collection); and Stampfle 1991, 46 – 48, no. 77.

Hondius’s Farmhouse at Wijnegem in the Rijksprentenkabinet, for example, is a copy after a drawing by an unidentified Flemish artist in the Louvre; for which see Schapelhouman 1987, 54 – 55, no. 34. Hondius also made a number of drawn copies of prints by Lucas van Leyden; see Packer 2015.

New Hollstein (Hendrick Hondius), 68, no. 55. This print was also used two years later in 1614 to illustrate Samuel Marolois’s treatise on perspective, and in subsequent editions.