Choose a background colour

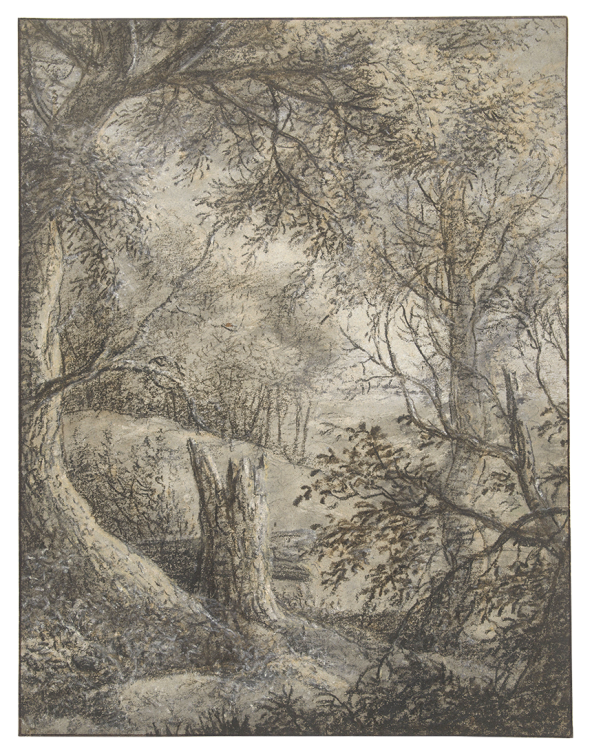

Anthonie Waterloo, Dutch, 1609-1690: Landscape with Trees by a River, c. 1670

Black chalk, oiled black chalk, and gray wash heightened with white on gray paper.

6 15⁄16 × 8 1⁄16 in. (17.6 × 20.4 cm)

Verso, upper right, in pencil, Wilhem von Bemmel / [illegible word], center, XII 12, lower left, Antoine Waterloo 1618 – 1662, and lower center, DK 4632.

- Chain Lines:

- Indiscernible.

- Watermark:

- None.

- Provenance:

Arthur Feldmann, 1877 – 1941, Brno; looted by the Gestapo in 1939 during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia; in the possession of the Czech government until 1956, when accessioned by the National Gallery, Prague (inv. no. DK 4632, stamp on verso, NGGS / PRAHA, not in Lugt); restituted to the heirs of Arthur Feldmann in 2013; sale, Sotheby’s, London, 9 July 2014, lot 111; Sheldon and Leena Peck, Boston (Lugt 3847); gift to the Ackland Art Museum, inv. no. 2017.1.96.

- Literature/Exhibitions:

None.

- Ackland Catalogue:

- 2017.1.96

As suggested by his numerous topographic landscape drawings, Anthonie Waterloo was an enthusiastic traveler. Between 1655 and 1660 he visited places in the Netherlands, northern Germany, Poland, France, and perhaps even Italy. This drawing, created some ten to twenty years later, appears to be a studio production and demonstrates Waterloo’s more expressive and inventive approach. Using different media in various colors on colored or prepared paper, the artist produced a distinctive woodland view in which the viewer is placed within the shadow of a dense forest, looking out toward a sundrenched vista beyond.

Although nominally a painter by occupation, and often listed as such in archival records, very few paintings by Anthonie Waterloo have come down to us.1

He is best known today for his etchings, numbering about 140 plates, that were frequently reprinted well into the eighteenth century, and for his even larger number of drawings, for which there remains no catalogue, but which must total several hundred sheets. Waterloo has often been described as a reislustige, or “travel-happy” artist. The label is apt since identifiable places in his numerous topographic landscape drawings reveal voyages taken down the Rhine, through Northern Germany, and into Poland as far as Danzig (Gdansk), as well as France and perhaps even Italy.2

His far-reaching trips have been placed around 1655 – 60, but Christiaan van Eeghen recently pointed to some likely excursions within the United Provinces taken with his apparent mentor, Simon de Vlieger (1600/01 – 1653).3

Many of Waterloo’s large black chalk landscape drawings remain difficult to distinguish from those by De Vlieger.4

The present drawing shows Waterloo working in one of his most distinctive and creative modes, combining a number of different media in various colors and on colored or prepared paper to generate dense and intimate woodland views. His use of pitch-black oiled chalk or charcoal in the foreground produces zones of spatial recession that lead our eyes through the image. A similar drawing in the Rijksmuseum appears to be much in the same vein, with broken vegetation and fallen trees Fig. 61.1.5

Anthonie Waterloo, Woodland Scene with Fallen Tree. Black, white, and yellow chalk, gray wash, charcoal soaked in linseed oil, on gray paper, 338 × 260 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-T-1955 – 157

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

It has proven difficult to date these works, but they appear to be studio productions from later in Waterloo’s career, perhaps from the 1670s, long after his traveling years were behind him.6

Perhaps no more than two dozen of Waterloo’s drawings display this imaginative and expressive side of his character, works that seem to presage an Romantic-era spirit.

The provenance of this sheet has a darker side. It once belonged to the Czech lawyer, Arthur Feldmann (1877 – 1941), whose collection of old master drawings was famed throughout Europe.7

It apparently numbered over 750 works, though it was never fully catalogued before being seized by the Nazis along with all of his other property.8

Feldmann suffered a stroke under torture and died a few days later. His wife likewise met her demise at Auschwitz, though their children managed to emigrate. This drawing was restituted to the Feldmann heirs in 2013, after which it was sold at auction with other restituted works. Despite the many decades since the war, such cases serve as important reminders that the process of restitution still continues. The present drawing is published here for the first time.

End Notes

For biographical data, see Kahn-Gerzon 1992.

For these travels, see Stubbe & Stubbe 1983 (covering specifically his travels in Northern Germany); Kahn-Gerzon 1992, 94; and Buvelot 2010.

Van Eeghen 2015, 313, 331, 332.

See Van Eeghen 2015, which attempts to distinguish their hands in a number of sheets.

Schapelhouman & Schatborn 1987, no. 78. An older attribution of this drawing to Willem van Bemmel (1630 – 1708) written anonymously on the verso is worth mentioning since his style is indeed close; see, for example, a drawing by him dated 1660 in the Herzog Anton Urich Museum, Braunschweig (https://rkd.nl/explore/images/285074), but the attribution to Waterloo was confirmed by Martin Royalton-Kisch in 1995, according to an inscription on the older mount. Waterloo’s foliage tends to be sharper and more abrupt, as in the Peck drawing, by comparison to Van Bemmel’s.

A drawing that bears stylistic relation to this group in the Lehman Collection (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 820) bears notes in Waterloo’s hand on the verso that can be dated around 1676, for which see Kahn-Gerzon 1992, 96. See also in relation to dating a similar drawing, D. Mandrella in Chantilly 2001, 150 – 51, under no. 80.

For the story of Arthur Feldmann, his family, and his collection, see (with further references) the biographical note on the British Museum website: https:// www.britishmuseum.org/collection /term/BIOG27053.

Despite the fact that the collection was never fully catalogued, much of it appeared on the auction block in 1934, though not the present drawing, with Feldmann remaining anonymous (see the sale catalogue, with an introduction by Otto Benesch, Gilhofer & Ranschburg 28 June 1934). Many of the lots remained unsold and were returned to Feldmann before being looted by the Gestapo. My thanks to Bill Robinson for this information.