Article: The Dutch Realist Landscape

Focus on the Peck Feature

During the early decades of the seventeenth century in the Netherlands, a new generation of artists active in Haarlem embraced representations of the local environs around them. Sweeping, grandiose, and idealized landscape depictions of the previous century were replaced by simple, intimate, and unpretentious subjects based on direct observation. This Focus on the Peck Collection installation presents the work of three artists who were instrumental in promoting this new landscape style. Two drawings from the Peck Collection by Jan van Goyen and Pieter de Molijn are shown together with a painting by Salomon van Ruysdael. Each river scene shares common elements, such as a low horizon line, trees that punctuate the sky, and human activity in nature, creating a harmonious and realistic impression of the low-lying Dutch landscape.

During the early decades of the seventeenth century in the Netherlands, a new generation of artists active in Haarlem abandoned the sweeping, grandiose, and idealized landscape depictions of the previous century. Instead, they embraced representations of the local environs around them featuring simple, intimate, and unpretentious views based on direct observation. Factors such as Protestantism and an increase in secular subjects, growing urbanization and a desire for the countryside, nationalistic pride, and large-scale reclamation projects, amongst others, contributed to this new approach. Using studies drawn from life and carefully composed “realistic” views of the Dutch countryside, artists portrayed rivers, streams, beaches, dunes, fields, forests, and country roads with sensitivity and expressiveness that appealed to patrons and art lovers alike.

This Focus on the Peck Collection installation presents the work of three artists who were instrumental in promoting this new landscape style. Two drawings from the Peck Collection by Jan van Goyen and Pieter de Molijn are shown together with a painting by Salomon van Ruysdael. The objects span seventeen years, from 1626 to 1643, and demonstrate the artists’ similar approach to subject matter and compositional arrangement. Each river scene shares common elements: a low horizon line, a dark foreground, tall trees that punctuate the sky, an urban profile in the distance, a palpably moist environment, a convincing impression of light and space, and human activity that is in harmony with nature.

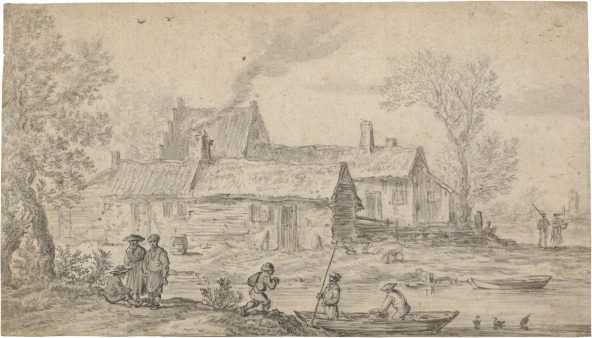

Jan van Goyen, Figures, Boats, and Cottages on the Banks of an Estuary, 1626

Jan van Goyen, Dutch, 1596 – 1656. Figures, Boats, and Cottages on the Banks of an Estuary, 1626, black chalk and gray wash on paper, The Peck Collection, 2017.1.40.

See Figures, Boats, and Cottages on the Banks of an Estuary in more detail here.

In 1617, Jan van Goyen trained in Haarlem with Esaias van de Velde, a forerunner of the new naturalistic landscape style. Absorbing elements of his teacher’s work, Van Goyen created his own unique style and became one of the most influential landscape artists of his time. Over his long and prolific career, he derived inspiration from the local scenery he experienced during his extensive travels in the Dutch countryside.

In this early drawing, two large houses serve as a backdrop to the animated action occurring along the riverbank. Van Goyen represents space and depth convincingly by dividing the scene into horizontal bands and by using clear tonal gradations, from dark and clearly defined elements in the foreground to less distinct and looser forms in the background.

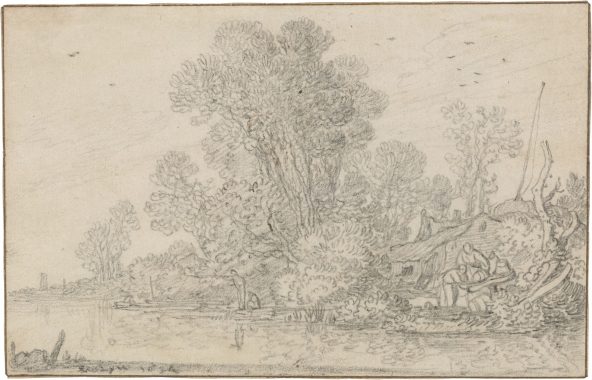

Pieter de Molijn, Wooded Riverbank with a Family Washing and Fishing, 1634

Pieter de Molijn, Dutch, 1595 – 1661, Wooded Riverbank with a Family Washing and Fishing, 1634, black chalk with touches of wash in brown ink on paper, The Peck Collection, 2017.1.56.

See Wooded Riverbank with a Family Washing and Fishing in more detail here.

Pieter de Molijn joined the painter’s guild of Saint Luke in Haarlem in 1616 and remained in the city until his death forty-five years later. Like Jan van Goyen, he recorded rural landscape motifs from life and used sketches as source material for more carefully composed works. Using black chalk to render the effects of light and atmosphere, De Molijn portrays a cottage beside a stand of tall trees, its inhabitants washing and fishing along the river’s edge. Trees are described using energetic and rhythmic strokes, which become loose squiggles in the reflection of the water. Considered the artist’s only signed and dated drawing of this period, this sheet is a pivotal example of De Molijn’s lively drawing style of the 1630s.

Salomon van Ruysdael, River Landscape with Fishermen, 1643

Salomon van Ruysdael, Dutch, c. 1602 – 1670, River Landscape with Fishermen, 1643, oil on panel, The William A. Whitaker Foundation Art Fund, 2002.15.

See River Landscape with Fishermen in more detail here.

No known drawings are associated with Salomon van Ruysdael, but his paintings, especially of the 1630s, share a close aesthetic relationship with the works of his contemporaries Jan van Goyen and Pieter de Molijn. As in their landscapes, Van Ruysdael regularly featured waterways. As a plentiful resource, rivers and canals became central to Dutch economic, social, and cultural development.

Here, small boats ferry people across the calm water of a large river. Gray, windswept clouds blanket the foreground in shadow, while a band of light illuminates the urban town depicted along the low horizon in the background. Such contrasts of shadow and light heighten the illusion of space and depth to create a harmonious and realistic impression of the low-lying Dutch landscape.