Article: Marriage in the Early Modern Imagination

Focus on the Peck Feature

Marriage celebrations were a common motif in early modern European art. This Focus on the Peck Collection installation features two engravings from the sixteenth century and one preparatory drawing for an engraving from the eighteenth century depicting nuptial rituals. These three images demonstrate the wide application of weddings as a theme to comment on social issues as diverse as class, religion, and race.

This Focus on the Peck Collection installation juxtaposes three European meditations on marriage ceremonies, demonstrating the wide application of weddings as a theme to comment on social issues as diverse as class, religion, and race. Hans Sebald Beham’s series of four miniature engravings depicting figures in a procession offers a comical, if not condescending, look at the celebrations of sixteenth-century German peasants. Dirck Volkertsz Coornhert’s print of a New Testament parable explores the idea of religious sincerity through proper nuptial etiquette, while Bernard Picart’s drawing of an Inca wedding, though imagined through a European lens, highlights the universal importance of family and tradition.

Despite the similar subject matter of the three works, each offers a specific moral lesson. Beham’s peasants reinforce class distinctions, while Coornhert emphasizes religious earnestness. Picart’s drawing was made into an engraving for the widely printed book Religious Ceremonies and Customs of All the Peoples of the World (1723-37), a groundbreaking publication which provided Europeans a glimpse of religious and cultural practices from around the globe and stressed the need for tolerance of other races and religions.

Viewed together, these objects demonstrate the ways in which the same custom can inform many different societal issues through visual representations.

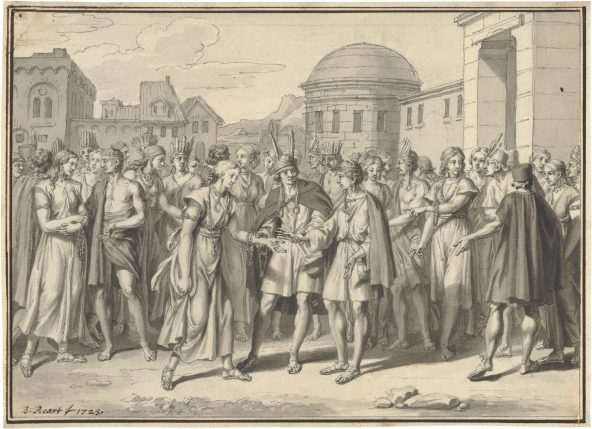

An Inca Wedding, 1723

Bernard Picart, French, 1673 – 1733, An Inca Wedding, 1723, pen and gray ink, gray wash on paper, The Peck Collection, 2017.1.116.

See An Inca Wedding in more detail here.

A robed elder clasps the wrists of a young Inca couple about to be joined in marriage, surrounded by an animated crowd in an open town square. Although the artist advocated for the appreciation of foreign cultures, Bernard Picart never left Europe and instead depended on descriptions from travel accounts to create his drawings. Organized like a grand eighteenth-century history painting, featuring classicizing garments and domed architecture, only the elaborate jewelry and feather headdresses vaguely reference Inca culture.

This imagined wedding ceremony accompanied a text which stressed the highly organized society of South America’s indigenous peoples. Picart deliberately avoided more disparaging themes, such as human sacrifice, and instead focused on the commonalities between cultures. The wedding motif used here highlights the shared devotion to family between the Inca and Europeans.

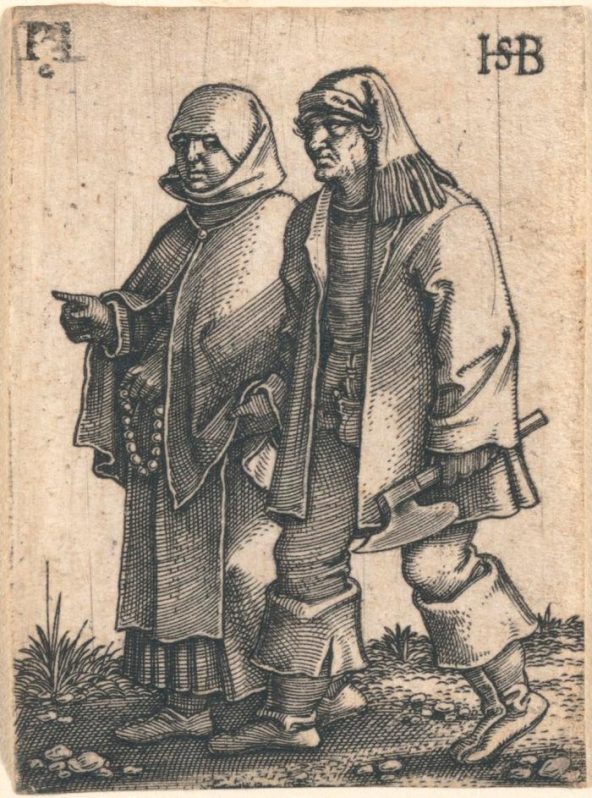

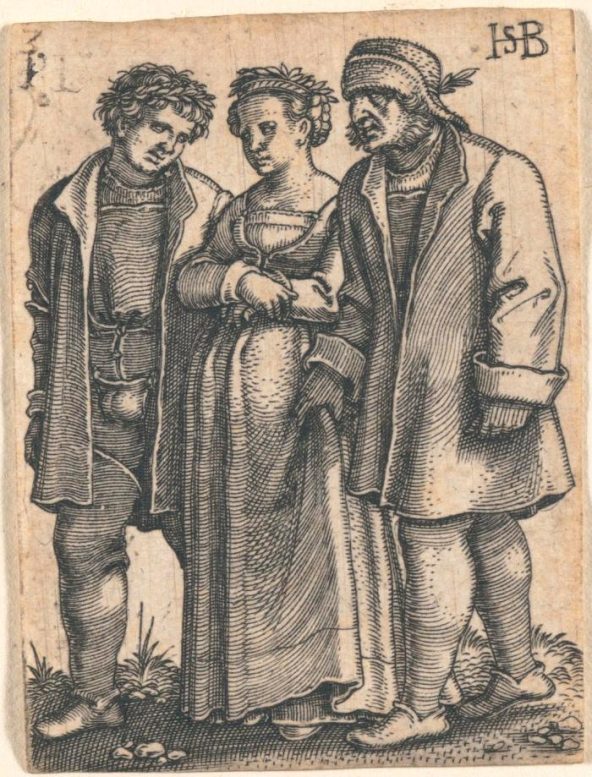

The Wedding Procession, mid-1530s

Hans Sebald Beham, German, 1500 – 1550, Couple Dancing to the Left, from The Wedding Procession, mid-1530s, engravings, Burton Emmett Collection, 58.1.227

Hans Sebald Beham, German, 1500 – 1550, Couple Walking to the Left, from The Wedding Procession, mid-1530s, engravings, Burton Emmett Collection, 58.1.228

Hans Sebald Beham, German, 1500 – 1550, Couple Walking to the Left, from The Wedding Procession, mid-1530s, engravings, Burton Emmett Collection, 58.1.229.

Hans Sebald Beham, German, 1500 – 1550, Bride and Bridegroom, mid-1530s, engravings, Burton Emmett Collection, 58.1.230.

View Couple Dancing to the Left, Couple Walking to the Left (a), Couple Walking to the Left (b), and Bride and Bridegroom from the Wedding Procession here.

Peasant celebrations were a popular theme in northern European art during the sixteenth century. These miniature engravings, meant to entertain a bourgeois audience, capture the rustic and somewhat humorous guests of a peasant wedding. In the first image a man exuberantly leads a more reluctant partner into a dance, while the next depicts a pious older couple with overly sober expressions. A third pair chats animatedly, with the man’s face contorted into a caricature-like expression. The final image depicts the newlyweds, identified by their matching bridal wreaths, though the bride’s father, shown protectively clutching her skirts, seems reluctant to let her go. The collectors of these prints would have delighted in the familiar traditions of a German wedding coupled with the strange and rough manners of the peasants.

The Fate of the Man who Came without a Wedding Garment, from The Parable of the King who Prepared for a Wedding, 1558-59

Dirck Volkertsz. Coornhert, Netherlandish, 1519 – 1590, engraver, Maerten van Heemskerck, Dutch, 1498 – 1574, designer, Hieronymus Cock, Flemish, 1518 – 1570, publisher, The Fate of the Man who Came without a Wedding Garment, from The Parable of the King who Prepared for a Wedding, 1558-59, engraving and etching on paper, The Robert Myers Collection, 2019.42.2.6.

See The Fate of the Man who Came without a Wedding Garment in more detail here.

This image is one of six illustrating episodes in the biblical parable about a king who prepared for his son’s marriage feast (Matthew 22:1-14). In this final scene, a man arrives improperly dressed and is forcibly dismissed. Two moments are represented here, including the rather dramatic expulsion of the man, who is lowered into a fiery pit in the background. While the king’s actions might appear unjust, the unwelcome guest represents those who claim admittance to the kingdom of God without truly clothing themselves in faith. Here, full participation in the wedding customs is a metaphor for the life of a good Christian.

Unlike Bernard Picart’s celebration of universal customs across cultures in the eighteenth century, sixteenth-century viewers would have understood this image as a reminder of the exclusivity of Christian traditions and salvation.

Sarah Farkas, Ackland Graduate Intern and Graduate Student in the Department of Art & Art History (as of summer 2021)