Article: Botanical Works on Paper

Focus on the Peck Feature

During the seventeenth century, Dutch botanists, merchants, and artists turned their attention to vegetation, near and far. Intellectual hubs like the University of Leiden cultivated some of the first botanical gardens while amateur flower enthusiasts took an interest in personal horticulture.

This Focus on the Peck Collection installation celebrates the arrival of Spring through two artist’s renditions of weeds and everyday plants. These botanical works by Dutch draftsman Crispijn de Passé the Elder (c.1565-1637), alongside a much later work by French engraver Eugène-Stanislas-Alexandre Blery (1805-1887), depict familiar vegetation with uncommon vitality and detail. Together, they showcase how artists elevate ordinary, yet visually expressive plant life to unexpected prominence.

During the seventeenth century, Dutch botanists, merchants, and artists turned their attention to vegetation, near and far. Intellectual hubs like the University of Leiden cultivated some of the first botanical gardens while amateur flower enthusiasts took an interest in personal horticulture. Although colonial traders in the Dutch East India Company introduced many new species to the Low Countries, Dutch artists continued to capture the vibrancy of seemingly mundane, local flora.

This Focus on the Peck Collection installation celebrates the arrival of Spring through two artist’s renditions of weeds and everyday plants. These botanical works by Dutch draftsman Crispijn de Passé the Elder, alongside a much later work by French engraver Eugène-Stanislas-Alexandre Blery, depict familiar vegetation with uncommon vitality and detail. De Passé, as head of a prominent family of engravers, drafted portraits of nobility, biblical scenes, and botanical treatises. The pen and ink works presented here may have been studies for a printed floral pattern book, used primarily by artists, or for the herbarium Hortus Floridus (1614), intended for botanists and gardeners. With Blery’s dramatic engraving of the common pastoral weed coltsfoot, the works showcase how artists elevate common, yet visually expressive plant life to unexpected prominence.

Studies of Mallow and Nightshade

Crispijn de Passé the Elder, Dutch, c. 1565 – 1637, Studies of Mallow and Nightshade, c. 1600, pen and brown ink and brown wash, The Peck Collection, 2017.1.60.

See Studies of Mallow and Nightshade in more detail here.

These sensitive drawings offer an intimate look at Crispijn de Passé’s artistic process beyond his more well-known engravings. Here, he renders two divergent silhouettes of mallow and nightshade. On the left, the curvilinear form of mallow — composed of shapely leaves and flowing petals — imparts liveliness to the drawing. As a common medicinal plant, images of mallow frequently appear in herbariums and pharmacological books. Mallow here is paired with nightshade, often associated with death due to its toxic berries, and together the two studies evoke the theme of life’s transience or vanitas. De Passé often incorporated vanitas symbolism into his religious prints, but identifying a deeper meaning between this pairing proves difficult without additional visual clues.

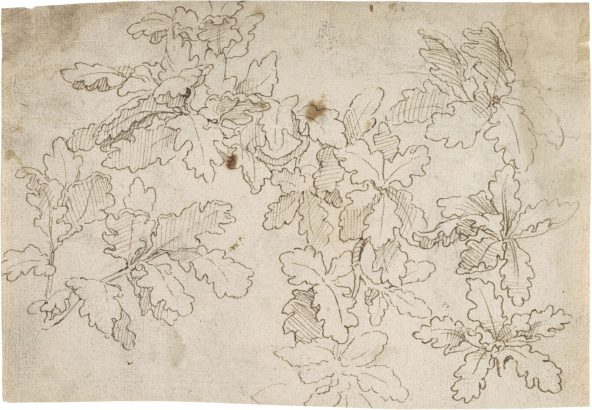

Studies of Oak Branches and Leaves

Crispijn de Passé the Elder, Dutch, c. 1565 – 1637, Studies of Oak Branches and Leaves, c. 1600, pen and brown ink, The Peck Collection, 2017.1.59.

See Studies of Oak Branches and Leaves in more detail here.

De Passé’s depiction of sprawling foliage spills across the composition. Rather than employing the defined linework seen in his drawings of mallow and nightshade, de Passé contours these oak leaves with errant hatching and loose pen strokes. Oak trees were a common sight in the forests of northern Europe, and by the seventeenth century they were associated with virtues of strength and resilience. Like his studies above, however, it is difficult to attribute these interpretations to De Passé’s drawing without further context.

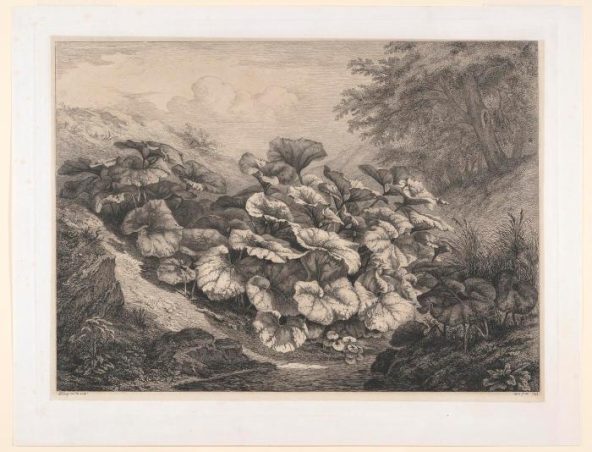

Coltsfoot

Eugène-Stanislas-Alexandre Blery, French, 1805 – 1887, Coltsfoot, 1843, etching, Gift of Charles Millard, 91.76.

See Coltsfoot in more detail here.

In the mid-nineteenth century, lithographer, painter, and engraver Eugène Blery gained recognition for his detailed landscapes and botanical prints. Inspired by his tours of pastoral France, Blery devoted himself to a printmaking career that captured the dynamic outdoors. In this etching, Blery elevates a common weed of the French countryside into a dramatic focal point using a combination of naturalistic detail and fantastical perspective. Occupying the composition’s middle ground, the gargantuan leaves of the coltsfoot unfurl from delicate stems. Sharp contrasts of light and dark invite the viewer into the shady canopy underlying this vegetal palace while the hazy and diminutive outline of a tree, in the background, secures the grand scale of this majestic, wild plant. Instead of the symbolic evocation found in De Passé’s drawings, Blery’s print denotes grandeur through its unique scale and perspective.

Amrut Mishra, Ackland Graduate Intern and PhD Candidate in the Department of Communication (as of summer 2022)